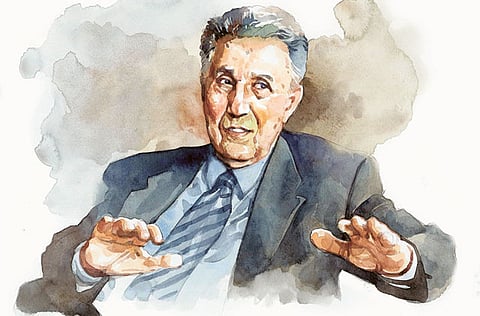

Ahmad Bin Bella: The man who went too far

Independent Algeria's first president, Ahmad Bin Bella, was not content freeing his country from the French. He strove for a world free of imperialism

One of the great figures of Arab nationalism, Ahmad Bin Bella was a founding-member of the Committee of Algerian Revolutionaries that, in time, gave birth to the Jabhat Al Tahrir Al Watani or the Front de Libération Nationale (FLN). A perennial foe of French occupation, he was arrested in 1952, before he escaped and was rearrested in 1956 along with seven fellow freedom fighters.

Bin Bella was a prisoner at the infamous "La Santé" jail until 1962, though he utilised his incarceration well: He learnt Arabic at the Paris prison. Ever so popular, even in detention, the French orchestrated an understanding with the FLN, and pursuaded Bin Bella to sign the Evian Accord, which catapulted him to the presidency of independent Algeria.

As head of state, he favoured socialism along with a vast programme of agrarian reforms. Under Bin Bella, an avowed anti-imperialist, Algiers hosted the world's rising socialist stars — from Che Guevara to Fidel Castro — and reinvigorated the non-aligned movement by offering an alternative to both East and West.

Although impossible to verify, great powers, who were unhappy with him, are said to have supported the military coup d'état that ousted him from power in 1965. This was followed by a long house arrest until 1980. Bin Bella suffered "memory losses", and his mental state apparently "deteriorated significantly" after his wife Zohrah Sellami died of lung cancer in April 2008 at the age of 70. After 1999, though a vocal critic of imperialist ambitions in the Arab and Muslim worlds and despite the 24 years he spent as a prisoner of both the French colonial regime and its nationalist successors taking a toll on his health, the frail Bin Bella remained close to Algerian officials.

A loyal friend to a disloyal army

Bin Bella was a product of French colonialism and barely spoke his native Arabic while growing up. Like many "French Algerians" from poor or modest backgrounds, he volunteered for service in the French Army in 1936, given that the military was one of the few avenues of advancement for Algerian Muslims under colonial rule. An athletic figure, the young Bin Bella played football for Marseille.

The club offered him a professional spot in 1939-1940 but he rejected the offer to return to his native country. In 1940, he was awarded the Croix de Guerre and he stayed with an infantry regiment — the Moroccan Tirailleurs — and fought in Italy.

The Commander of the Forces Françaises Libres (FFL or Free French Forces), General Charles de Gaulle, awarded him the Médaille Militaire for bravery at the 1944 Monte Cassino battle near Rome that caused an estimated 70,000 deaths. Bin Bella, though, was shocked to learn of the May 8, 1945, Sétif massacres, in which an estimated 6,000 (the figure remains disputed) Algerians lost their lives. He returned to his native land after the war, disillusioned with the French and their repression of Muslims.

If his awakening occurred on European soil, the mobiliser in him matured after he founded the Organisation Spéciale (OS), an underground unit pledged to fight colonial rule. In time, the OS grew into the FLN, becoming a thorn in the side of French authorities who, more often than not, responded with increasingly harsh treatments.

Bin Bella was arrested in 1951, sentenced to eight years' imprisonment. Two years later, he escaped from the Blidah prison, first to Tunisia and from there to Cairo to join fellow Algerians receiving Egyptian protection and support. What followed was a protracted conflict, as the FLN fought Colonial France for independence, it was buoyed by Jamal Abdul Nasser's rise in international affairs and the financial, military and logistical assistance extended by revolutionary Egypt. Many, including Nasser, believed that Paris favoured independence because prime minister Guy Mollet was a socialist who, allegedly, was opposed to colonialism.

Speaking with Swiss journalist Silvia Cattori in 2006, Bin Bella recalled how the FLN fared at the hand of socialists, as Mollet contacted Nasser to ascertain whether Algerian freedom fighters were ready to negotiate a transition.

Ben Bella favoured such talks, provided Paris put in a formal request, and actually held three-month-long discussions in Cairo. Because both Morocco and Tunisia assisted the FLN militarily, Bin Bella flew to Rabat to inform Mohammad V, but while on his way to Tunis to share his news with Habib Bourguiba, the French Air Force diverted the aircraft carrying two-thirds of the FLN leadership to France. Mollet ordered everyone's arrest.

Bin Bella stayed in prison from 1956 to 1962, but that did not prevent his election to the vice-premiership of the Algerian provisional government.

He quickly challenged prime minister Benyoucef Benkhedda for the top post. Supported by the armed forces and its military hero, Houari Boumédiènne, Bin Bella was essentially in control of Algeria by September 1962.

His government was recognised by the United States on September 29 as Algeria became the 109th member of the UN on October 8. Running unopposed for the presidency in 1963, the popular Bin Bella devoted all of his attention to land reforms that, at least technically, benefited landless farmers.

His "autogestion" (self-management) policy was highly controversial since it tolerated the confiscation of lands seized from French owners, but the more serious clashes within the FLN leadership were on Bin Bella's internationalist attention. Consequently, former guerrillas had a difficult transition to bureaucratisation, which necessitated autocratic rule.

Past supporters objected to his revolutionary foreign-policy preoccupations that presumably distanced him from domestic needs. Although Bin Bella received many awards, including the flamboyant title of Hero of the Soviet Union, on April 30, 1964, he was unable to concentrate on securing the progress in developing national state structures. Simultaneously, Boumédiènne feared a weakening of the army's legitimising role within Algerian society, which was the main reason for the 1965 coup.

The coup d'état of June 20, 1965

In the early hours of June 20, tanks moved into position at the presidential villa in Algiers and various strategic points in the city, while the airport also came under military control. Naturally, communications with the outside world were cut off, and while demonstrators took to the streets chanting slogans in support of deposed president Bin Bella, few understood what actually happened.

Algiers radio played military music until colonel Boumédiènne broadcast a long statement accusing Bin Bella of treason. He revealed that the former president was being held prisoner in a remote Sahara outpost, and promised him the "fate of all despots", which was disquieting to say the least.

The respected officer pledged to work for a "democratic, serious state" and the recovery of the economy, which implied that Algeria had become an unreliable entity and had suffered from mismanagement. Interestingly, Boumédiènne gave assurances that no foreign property — meaning those under French ownership — would be confiscated, which led many to conclude that the coup was orchestrated by Paris. Equally plausible was the speculation that Moscow may have nudged the beholden military to move against Bin Bella who, in an uncharacteristic step, excluded the USSR from the Afro-Asian Conference that was due to be held in the capital less than a fortnight hence.

A more likely scenario was Bin Bella's falling-out with Boumédiènne, who feared for the fate of his beloved military, since Bin Bella favoured a political institutionalisation process. By reconstituting the government to respecting the idea of a supreme "state", rather than a government beholden to a single institution that guaranteed its survival, Bin Bella signalled that the military would need to come under civilian rule.

Though Bin Bella rightfully resented his mistreatment at the hands of his French captors, he was bitterer towards his own brothers in arms who kept him under house arrest for 15 years.

He seldom spoke about Boumédiènne, though in 2006 he told Silvia Cattori: "I don't feel contempt, I don't feel hate. I think that they participated in something that was not very proper and was very pitiful, not only for the Algerian people, but also for the other people who counted on our support.

"My fight to bring better conditions of life to Algerians thus plunged into great poverty, and my fight to help other still colonised people to recover their freedom bothered certain authorities. From their point of view, I had gone too far. I had to disappear. That is to say, if the Algerian army had not overthrown me, others would have done so. I had to disappear, because I had become too much of a nuisance. I accommodated practically all of the liberation movements, including those of Latin America. Che came in 1963, shortly after I had come to power. With my government, we engaged in bringing our help to fights for national freedom. At that precise moment, several countries were still colonised or had barely overcome colonisation. This was the case in practically all of Africa. We supported them. Mr Mandela and Mr Amilcar Cabral themselves came to Algeria. It's me who coached them; afterwards they returned to lead the fight for freedom in their countries. For other movements, which were not involved in a military fight and who needed only political support, such as Mali, we helped in other ways."

This was the revolutionary stance that defined Bin Bella, who was finally released on orders from president Chadli Bendjedid in 1980, when he moved to Switzerland to live in exile.

A decade later, Bin Bella was allowed to return and stand for the presidency of the Mouvement Démocratique Algérien (MDA), though the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS) won the 1991 elections. Algiers promptly annulled these results and sent Bin Bella back to his Lausanne exile. Regrettably, attempts to introduce a multi-party democracy failed, as violence prevented the rise of a functioning state that served its own sons and daughters.

Over the years, Ben Bella became an Arab Islamist, but he welcomed the establishment of various political parties in his country. No longer was he an advocate of a single-party entity, persuaded that Algeria, indeed all Arab and Muslim states, deserved democratisation.

Interestingly, he rejected the recent Islamist cacophony that prompted outsiders to describe Islam as a violent faith, often focusing on narrow interpretations that portrayed a billion-plus people in a negative light.

Despite the fact that he remained a controversial figure, the former Algerian president steadfastly opposed colonial and neo-colonial rules, including the 2003 US invasion and occupation of Iraq. "It's intolerable to see what one has done in Iraq," he declared, lamenting the tragedy that befell "the cradle of civilisation".

Always opposed to Washington, Bin Bella noted that Iraq was where man "started to cultivate the land … where humanity was born … where the first principles were based … where the alphabet was created, [and where] the first code … that of Hammurabi" came into existence. "All of this was destroyed by ignorant leaders," he said, "by a nation that has no more than 250 years of history, which was itself a colony of Great Britain. They rid themselves of British colonialism and established a worldwide colonialism. What became of the 80 million American Indians? I will never return to America, it's a country of crooks."

Legacy

Bin Bella may be classified as a leftist leader, though not a strict Marxist, preferring to define himself as a Muslim Arab. Still, he rejected Muslim fundamentalism, and while he favoured socialist countries such as Cuba, China and the USSR, allegedly because the latter led anti-colonialist and anti-imperialist struggles, his efforts were mostly driven by a quest for liberation.

As a devout Muslim, he chose to overlook the USSR's imperialist drives and fell for Che Guevara's charm, even if Moscow's treatment of Muslims was ghastly.

Algiers under Bin Bella gave concrete support to liberation movements that fought colonialism, though it neglected to concentrate on the home front to build a self-sufficient country that empowered citizens. While few denied that colonialism was repressive, even fewer were in a position to glorify armed struggle that sacrificed a nation for chimerical goods, even if nationalist fervour often exacted such costs.

Dr Joseph A. Kéchichian is an author, most recently of Faysal: Saudi Arabia's King for All Seasons (2008).

Published on the third Friday of each month, this article is part of a series on Arab leaders who greatly influenced political affairs in the Middle East.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox