Israel and Turkey have reached a deal to normalise relations that soured after a 2010 Israeli raid on an aid flotilla that left ten Turkish nationals dead. Here are some questions and answers on the agreement:

Why is it significant?

Nato member Turkey and Israel are two key Middle Eastern powers at a time when Western nations are seeking cooperation in the fight against extremists from Daesh, also known as Islamic State. Israel is also deeply concerned with limiting the regional influence of its arch-foe Iran, and Turkey and Iran remain on opposing sides of the five-year civil war in Syria. There are also important economic and energy considerations.

Why now?

Turkey has been moving to restore its waning regional clout after a drastic worsening of its ties with Russia following Ankara’s downing of a Russian warplane over Syria on November 24. Besides downgraded relations with Israel, Ankara has also reduced ties with Egypt and has failed to oust Syrian President Bashar Al Assad. Israel was also motivated to find new allies in the region, in part due to a need for export partners for its natural gas. There has been talk of building a pipeline to Turkey. It has also found itself under increasing pressure over the lack of any progress on peace efforts with the Palestinians and has sought to build relationships with regional countries partly to counter such criticism.

What caused the dispute?

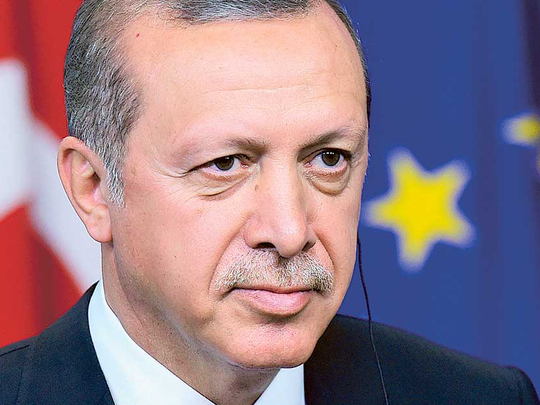

The Muslim majority country and the Jewish state were once close allies, but ambassadors were withdrawn following the deadly storming by Israeli commandos in 2010 of a Turkish aid ship bound for Gaza. The ship was part of a flotilla seeking to run Israel’s blockade of the Gaza Strip. Nine activists aboard the Turkish-owned Mavi Marmara ferry were killed, with a tenth person later dying of his wounds. All of those killed were Turkish nationals. Aside from the Mavi Marmara incident, Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, a stout supporter of the Palestinian cause, had raised hackles in Israel with his sometimes inflammatory rhetoric towards it.

What are the conditions of the deal?

The deal is to result in the restoration of ambassadors, an Israeli official said on condition of anonymity. Two of Turkey’s key conditions — an apology and compensation — were largely met earlier. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu apologised to Erdogan in a breakthrough engineered by US President Barack Obama during a visit to occupied Jerusalem in 2013. Israel has also agreed to pay some $20 million (Dh73.6 million) into a fund for compensation for the Turkish victims’ families, and in return all claims against Israeli soldiers will be dropped. The third demand — that Israel lift its blockade on the Hamas-run Gaza Strip — proved the toughest to overcome. A compromise was reached in which Israel will reportedly allow the completion of a much-needed hospital in Gaza, as well as the construction of a new power station and a desalination plant for drinking water.

Working with Hamas

Turkey’s aid to Gaza would also be channelled through the Israeli port of Ashdod rather than sending it directly to the Palestinian enclave, reports say. Turkey has also committed to keeping Hamas from carrying out activities against Israel from its country. Hamas would continue to be able to operate from Turkey for diplomatic purposes, reports say. Erdogan has also agreed to assist in having Hamas hand over four missing Israelis, according to an Israeli official who spoke on condition of anonymity. They include the remains of two soldiers presumed dead and two civilians believed held alive by Hamas in Gaza.

Trade implications

Israel’s flourishing military trade with Turkey dried up during the estrangement and its tourism to Turkish resorts fell more than 80 per cent since 2009, according to officials in Ankara. Still, other business channels remained open and bilateral trade reached a record $4.4 billion in 2011, according to official Turkish figures, staying near that level last year.

Ankara’s energy hub ambitions

The mending of the rift is proceeding in tandem with negotiations to reunify the Mediterranean island of Cyprus, whose north has been occupied by the Turkish military since 1974. A solution to that conflict would allow Turkey to buy gas from Cyprus as well as Israel, bringing it closer to its long-held dream of becoming an energy hub between East and West.