Tunis When her daughter began wearing the Islamic headscarf three years ago, Amal Bennajeh was so upset that she kicked the teenagers out of the house. They have since reconciled their relationship, but not their views.

"I still don't approve of her clothing," says Amal, sunglasses perched on her coiffed hair. Her daughter, Rania Mkaddem, sits beside her, smiling patiently.

Their disagreement over Islamic dress mirrors a larger debate unleashed by revolution here last year that ended decades of dictatorship: Will the new Tunisia be a secular state, an Islamic one, or something in between?

How Tunisians handle the debate over religion — particularly in the writing of a new constitution now under way — could offer lessons for other Arab countries such as Egypt and Libya, where popular uprisings have empowered Islamists long persecuted by autocratic regimes.

Two secularist parties

Today in Tunisia, the moderate Islamist Al Nahda party leads a coalition government with two secularist parties and dominates a national assembly that is tasked with writing the new constitution.

Debate has focused on whether that constitution should invoke the Sharia, or "way" — roughly, the commandments and moral sense of the Quran.

In March, thousands of mainly Salafists marched in Tunis to demand Sharia and denounce, in the words of one placard, "secularist dogs".

The next day, Al Nahda pledged to keep the first article of the current constitution, which cites Islam as Tunisia's religion without referring to Sharia.

"Tunisia is a free, independent and sovereign state. Its religion is Islam, its language is Arabic and its type of government is the Republic," reads a translation provided by the University of Richmond in Virginia.

Secularist parties have welcomed the move.

Compromises

"We're in a transitional phase," says Nour Al Deen Arbaoui, a member of Al Nahda's executive bureau. "Tunisians must join together and make compromises for democratic transition to succeed."

"We in Al Nahda don't want a religious state, but nor is our state secular," he says. "We feel that the first article of the constitution is enough to meet people's desire that Islam play a leading role in Tunisian life."

However, the article invites interpretation, says Slim Laghmani, a law professor at Carthage University, near Tunis. He says that former presidents Habib Bourguiba and Zine Al Abidine Bin Ali used it to justify a half-century of aggressive secularism.

Bin Ali, who ruled from 1987 until he was ousted last year, outlawed Al Nahda and jailed thousands of conservative Muslims after the party scored well in the 1989 elections.

Polygamy

Bourguiba, his predecessor, considered Islam a barrier to building a modern state. During three decades in power he banned the headscarf and polygamy, expanded women's rights, and imprisoned Islamists.

For Amal, then growing up, Bourguiba's brand of modernity was a welcome contrast to the endless "no"s of her conservative mother.

"That I could go out of the house alone, that I could go to the cinema — these things that Bourguiba supported, my mother considered shameful," she says, now facing the opposite battle with her own daughter.

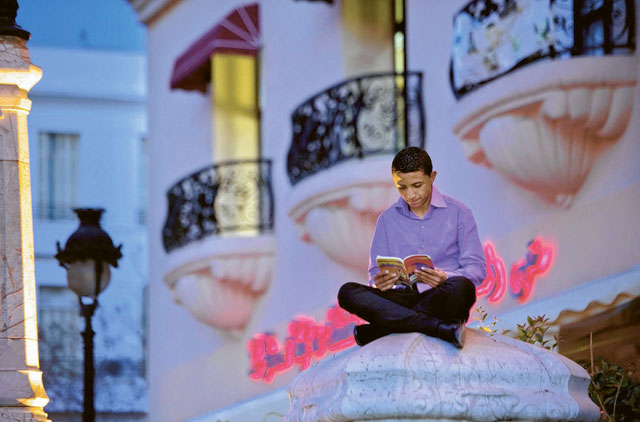

In 2009, Rania's interest in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict led her to Islamic piety. Told to leave home by her mother after donning the Islamic headscarf, Rania stayed for a month with an uncle before returning home and reconciling. Later, police near the college where she studies English language and literature forced her to sign a promise to remove her headscarf.

Freedoms

Amal sees danger not in secular policies, but in conservative Islam, which she fears could one day threaten her daughter's freedoms.

"Those who want Sharia think women aren't capable," she says. "But we're not asking for Sharia, just inspiration by Sharia," protests Rania, who argues that Islam protects women's dignity. Any use of Sharia as a basis for civil law is complex, says Slim Laghmani, a law professor at Carthage University, near Tunis. Sharia must first be distilled by scholars into regulations called fiqh. Once Tunisia's new constitution is written, elected lawmakers will have considerable influence over how it is applied.

"He who can impose his interpretation will give the text meaning," says Professor Laghmani.

Elections expected for next year that will shape the new government could thus do as much as Tunisia's constitution to determine the country's future, he says.