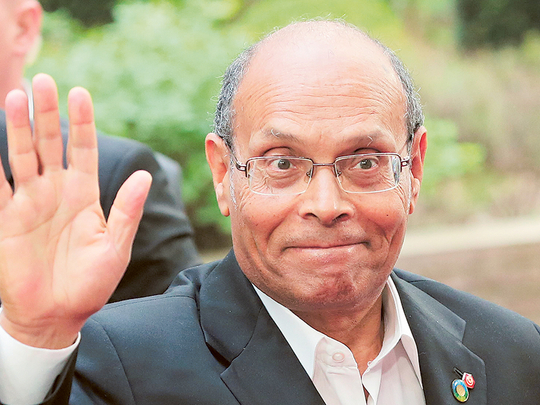

Tunis: Former Tunisian President Munsif Marzouqi talked with Bloomberg News reporter Jihen Laghmari in Tunis on September 30 about the North African country’s democratic transition.

Q: Tunisia is referred to as the Arab Spring success story, and yet we still see young people who are thinking about suicide as an act of protest. To an outsider this paradox is not easy to understand.

Marzouqi: Tunisia is a success story compared with the worst in the Arab Spring countries, but not compared to the best, which is what we wanted. The goals of the revolution were real democracy and fair development. The first part was partly achieved — we have had elections, probably not ones that were 100 per cent fair but it is a step forward toward democracy. But the second part hasn’t been. We’re afraid that the democratic success is threatened by the absence of this development, and that its absence may bring us back to the disorder and to square one. Lack of development pushes young people to despair and suicide because of the absence of a clear horizon.

Q: Is it a question of patience? Would a historian take the long view and say the transition is going well because transitions don’t happen overnight?

Marzouqi: Maybe it’s a matter of patience, transitional periods require a lot of time. Tunisia is looking for political stability because that will bring investment and create development. But the nature of ‘the political broth’ that has taken place in Tunisia doesn’t encourage investors, locals or foreigners. The message that investors take away is that the political situation is unstable: a ruling party explodes day after day, and the outlook is “foggy” because of the age of the president and because of the fragility of the consensus. It’s seen abroad as a consensus between all parties of the community but in truth it’s a consensus between only one part, with the other part, who carried out the revolution, completely excluded.

Q: What do you think of the current government line-up, and the measures they are proposing to fix the economy?

Marzouqi: I won’t be able to judge the results of the current government for a year at least ... but I have a great doubt that this government is able to survive a year. Its composition is very fragile, it isn’t homogeneous and is far from the concept of a national unity government. This government wants to review laws and give more powers to the president. We have not seen a clear economic programme and it will not have the political ability to face the crises that will unfold. I expect it will be a government that carries out instructions from the president of the republic.

There are three major problems in Tunisia — corruption, corruption, and corruption. We beg for funds from abroad, yet if we tried to solve the tax and collection problems, smuggling and the parallel economy, we would be facing the challenges with our own capabilities. Instead we leave all this bleeding and spend our time abroad begging for money that we may not be able to pay back.

Q: How do you see your role now?

Marzouqi: My role in opposition is preparing alternatives and to go to elections in 2019. We want to convince young people there’s still hope and that another election will rectify what happened in the previous elections because we’re in a democratic system that allows for a peaceful handover of power. This government, which came to power on false promises, will leave and power will return to the part of society that started the revolution for democracy and development. Young people aren’t convinced that upcoming elections carry hope and may bring the train back to the rails. But we’re trying to convince them to organise their anger in the framework of the system of democracy.