Fear comes in handy for Syria's President Al Assad

Masses betrayed by use of military and terror tactics after initial reform promises

Beirut: Falling back on the tactics that have kept his family in power for more than 40 years, Syrian President Bashar Al Assad is gambling that fear — not reform — will break the popular revolt against his autocratic rule.

Al Assad's initial reaction to the uprising that began last month was to couple dry promises of reform with force to quell the discontent and keep his grip on power.

But when protests only grew, he turned to his overwhelming military power, intimidation, and terror — methods perfected by his late father, Hafez, who crushed an uprising in 1982 by shelling the town of Hama. Amnesty International has claimed that 10,000-25,000 were killed, though conflicting figures exist and the Syrian government has made no official estimate.

Uncontested rule

For the next two decades, until his death, Hafez Al Assad ruled uncontested and the massacre was seared into the minds of Syrians.

Though Bashar Al Assad has not done anything on the scale of the Hama massacre in his 11 years in power, his crackdown in recent days has evoked memories of his father's brutal legacy.

"There is an element of ‘shock and awe' to the operation," said Joshua Landis, an American professor and Syria expert who runs an influential blog called Syria Comment. "Tanks are clearly not useful for suppressing an urban rebellion, but they demonstrate the superior firepower of the state and the determination of the president."

Sweeping arrests

The escalating crackdown, relying more each day on military force, has killed more than 150 Syrians just since the weekend.

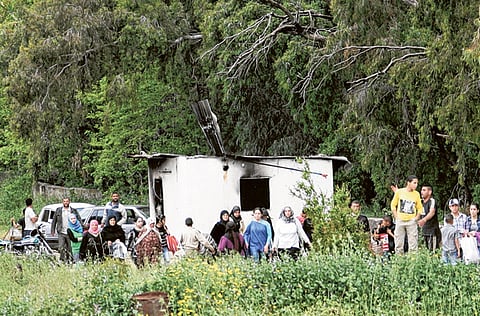

In a new phase that began this week, Al Assad sent thousands of soldiers rolling into cities, backed by tanks and snipers. His security forces made sweeping arrests, dragging people from their homes along with their families.

One Syrian in a city under military control said a man, his father and brothers were arrested just because they had an internet connection.

In Daraa, the now-besieged southern city where the uprising began five weeks ago, soldiers were stationed at cemeteries, keeping tabs on relatives of those killed protesting.

Water, power cut

Water and power have been cut in Daraa, with at least 42 people killed since troops stormed in, a rights activist said yesterday.

"The situation is worsening. We have neither doctors nor medical supplies, not even baby milk. The electricity is always cut and we haven't any more water," Abdullah Abazid said in Nicosia by telephone from Daraa, 100 kilometres south of Damascus.

The military deployment was an abrupt shift in strategy, from reacting to protests with force to pre-emptive military occupations of restive cities, towns and suburbs of the capital Damascus.

The use of overwhelming brute force to quell an uprising worked for Syria's close ally Iran when it quelled the 2009 ‘Green Revolution' triggered by a disputed presidential election.

Deadliest day of rebellion

On the deadliest day of the Syrian rebellion last Friday — when more than 100 people were killed — US President Barack Obama accused Al Assad of seeking Iranian help to use "the same brutal tactics" unleashed against demonstrators almost two years ago in Tehran.

Still, the stepped-up use of force show no signs of quelling the uprising in the short-term. To the contrary, the opposition has broken the barrier of fear, keeping up and stepping up their street protests despite the brutal crackdown that has killed more than 400 people since mid-March.

If anything, protesters enraged by the mounting death toll are escalating their demands to nothing less than the downfall of the regime. With that, the possibility of a drawn out and bloody conflict looms.

And unlike in Egypt and Tunisia, where popular uprisings succeeded in short order in upending a long-standing autocratic ruler, Syria's power structure is dominated by Al Assad's long-reigning Alawite sect that will be much harder to overturn.

Sectarian card

Al Assad has played on fears of sectarian strife — so clearly destructive in neighbouring Iraq and Lebanon — to persuade the public that the protests will bring nothing but chaos.

Syria has multiple sectarian divisions, largely kept in check under Al Assad's heavy hand and his regime's secular ideology. Most significantly, the majority of the population is Sunni Muslim, but Al Assad and the ruling elite belong to the minority Alawite sect.

Bleak outlook: army battles dilemma

The armies of Egypt and Tunisia sided with demonstrators in a final blow to the regimes, but Syria's protesters, cannot count on that kind of support.

Bashar Al Assad, and his father before him, stacked key military posts with members of their minority Alawite sect, ensuring the loyalty of the armed forces by melding the fate of the army and the regime.

So far, the military has stuck behind Al Assad, although there have been smatterings of dissent within the ranks. Two witnesses in Daraa said soldiers were refusing orders to detain people, instead allowing them to pass through checkpoints to find food and water, days after the water and electricity services were cut. Still, the resolve of protesters could buckle under a prolonged campaign of killings, beatings and torture.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox