Damascus: While still a student at Damascus University Law Faculty, Nizar Qabbani was approached by a classmate who asked: “The country is ablaze against the French and you are sitting there writing about women.”

He smiled and asked gently: “Why are we fighting the French?”

His friend snapped, “For independence.”

“No,” Qabbani retorted.

“We are doing it for freedom. Our country needs two legs to stand upright; one is independence and one is freedom and freedom starts with the emancipation of women!”

Nizar rejoiced like all Syrians of his generation, when the French ended its occupation of Syria in 1946.

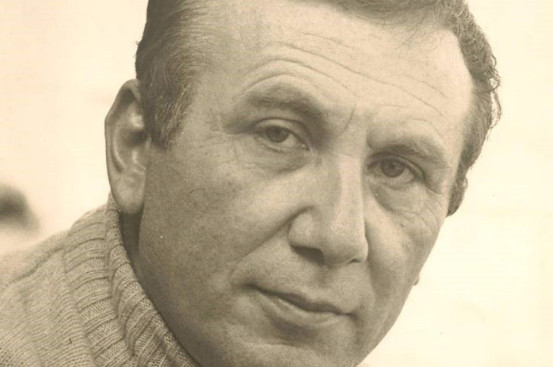

Today, it has been 19 years since the legendary Syrian poet died, but his iconic works remain as relevant as they were decades ago.

“He championed victims throughout his life,” says Nourallah Qaddura, a Dubai-based Syrian poet greatly inspired by Nizar Qabbani.

When he wasn’t writing about women, he penned nationalistic poems about the Arab struggle against Israeli oppression or US hegemony.

His works which focus on corruption, injustice and an end to military rule greatly resonate with Syria’s opposition today.

In 2011, Syrians across the country revolted against the decades-long Ba'ath party rule — one where dissent was not tolerated.

One poem in particular titled “Suppressionstan” hits home to many in the Syrian opposition. It reads:

‘Do you know who I am?

A citizen who lives in the state of Suppressionstan

One who dreams of one day reaching the rank of an animal …

A citizen who avoids sitting in cafes so that the “state” doesn’t jump out of the coffee cups

One who doesn’t cuddle his wife before the place is approved by security

I am just a citizen in the state of Suppressionstan.’

In another poem, he takes over the character of an Arab dictator and addresses the masses saying: “I am responsible for your dreams — if you do dream. I am responsible for every piece of bread that you eat. The security branch at my palace tells me everything — even what happens in the wombs of pregnant women!”

His prose got him into trouble throughout the Arab world, and his works were banned in Damascus, Baghdad, Cairo and Tripoli — with each security service getting hints that he was referring to its own leaders.

In fact, Qabbani only named two leaders directly in his works: once praising Jamal Abdul Nasser and second to trash his successor Anwar Al Sadat.

His death took Syria by storm when his coffin was transported from London to Damascus.

The entire city came out to the streets to bid him farewell, transforming the event into a thinly-veiled procession of “pride and dignity” for Syrians, who felt that they had lost one of their last standing icons.

Although occasionally visiting, Qabbani had not been to Damascus for years.

He moved to Beirut after the Baath Party seized power in 1963, resigning from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs where he worked since the mid-1940s.

He later moved to London where he lived in self-imposed exile until he died at the age of 75 on April 30, 1998.

Although he lived out his remaining years away, his love for Damascus never died.

“He loved the city to the point of fanaticism,” Qaddura said.

US-based Syrian playwright Riad Usmat was one of those who attended his funeral.

Remembering the event, he told Gulf News: “It was amazing how crowds rushed, gathered and filled the streets; men and women marched together defying the conventional traditions of separating sexes during Muslim burial. Many just wanted to touch the coffin of the legendary poet who glorified love and freedom, women and dignity, condemning all kinds of repressive authority.”

Qabbani left behind 33 books of poems and a handful of prose, in addition to thousands of recorded lectures, interviews, and a period article he used to write for the London daily Al Hayat.

Qabbani’s critics say he was full of contradictions — calling himself an Arab nationalist while trashing Arab leaders, customs etc.

He was critical of political Islam but a vocal admirer of the early Muslims of the Umayyad Era.

He hated military regimes but loved Nasser.

Although he was critical of Al Assad regime, a street was named after him in central Damascus in 1998, while he was on his deathbed.

Recently, a recital was staged at the Damascus Opera House in mid-April called “A Tribute to Nizar,” attended by Culture Minister Mohammad Al Ahmad.

Young artists performed songs composed to his poems by Um Kalthoum, Fairuz, Abdul Halim Hafez, and contemporaries like Kazem Al Saher and Majida Al Roumi.

It was followed by an art exhibition of work inspired by his works, displayed by 288 painters, and a bust of Nizar — the first ever for a contemporary poet.