Tripoli: Behind the high walls of a family compound in Libya's eastern capital, a giant photo of the late revolutionary commander General Abdul Fatah Younis smiles down on the dozens of men from his tribe who visit in a large tent after ending the Ramadan fast on a summer night.

Ali Senussi, a leader of the Obeidi tribe that Younis belonged to, sips tea in a plastic chair, looking grandfatherly in his traditional robe and vest. But as he speaks about the murky circumstances of the assassination of one of the tribe's own, he doesn't mince his words. The tribe will give the leadership a chance to investigate Younis' killing and bring those responsible to justice. But if they don't?

"The Obeidis are promising this will not go unpunished," he says. "We hope to be in a country of law and good judgment that ensures our rights without us having to take them ourselves. But if we needed to take our justice by ourselves, we will do it."

"Tribal law is stronger than the government law," adds a nearby tribal elder.

The Obeidi tribe's threat to take justice into its own hands illustrates the challenge that the new Libyan government will face not only in avoiding fighting or division between tribes, but also in ensuring the law reigns supreme over tribal traditions.

Identity

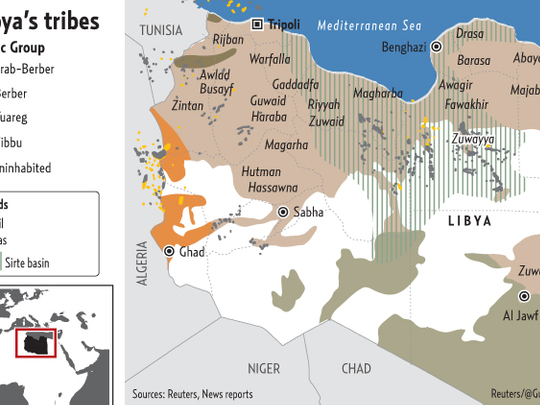

During his 42 years as leader of Libya, Muammar Gaddafi whittled away at state institutions, leaving little but himself at the centre of the nation. In the vacuum, Libya's strong tribal identity thrived, as did the divisions between tribes that Gaddafi cultivated. Now, in a new Libya that is free of Gaddafi, a key test will be whether the new government will have enough legitimacy to unite disparate tribes into a cohesive nation.

"Today what remains to be seen is whether Libya's new leaders can break free of the tribalism that has historically plagued the country and move to a more representative and geographically dispersed government," says Barak Barfi, a research fellow at the New America Foundation who has been in Libya researching the conflict for the past five months. "If they cannot do this, and continue to perpetuate the traditional political order, the new Libya will fail."

Tribalism runs deep in Libyan history, and tribal leaders are quick to extol the roles of their tribes in fighting Italian colonialism.

But tribalism still plays a role in society. For some Libyans, it is not uncommon to go to a tribal leader for help with a problem. Leaders can mediate disputes between members, secure release from jail, and intercede to settle intratribe disputes. For some, a tribal connection can create an instant bond with a stranger or be a means of career progression.

Gaddafi used the system to his advantage, rewarding tribes that were loyal to him and punishing those that were not, creating hostilities between them. As his regime falls, worries of tribal warfare and revenge abound.

In western Libya in July, Human Rights Watch reported that revolutionaries had burned and looted homes and shops belonging to Gaddafi supporters. But tribal leaders in the east say that while such violent revenge may happen to the former leader's most devoted supporters, they do not expect widespread retribution.

"It's not going to happen because all the people are supporting one thing: the revolution," says Khalil Mohammad Al Deeb, a leader in the Agouri tribe, a large tribe in eastern Libya that includes the majority of Benghazi citizens. For example, he says, one of the transitional council's leaders, Mahmoud Jabril, is from the Warfalla tribe. "They had a really bad role under Gaddafi," he says. "But we don't look at him as a Warfalla, we see him as an individual."

Some also say that the revolution has increased historically weak Libyan nationalism, which could lessen tribalism. "For 42 years, Gaddafi put hatred between the tribes. But this is the first time they feel like they are working together against something, and they like working together," says Deeb.

The revolutionary government has urged citizens to avoid revenge, and it has plans for a national reconciliation programme to keep tribal differences from festering.

But perhaps the biggest test is whether the government will be capable enough to supersede the tribal law that some revert to when the government is lacking. Several tribal leaders in eastern Libya asserted that in a democratic nation, tribes would play only social roles, not political ones.