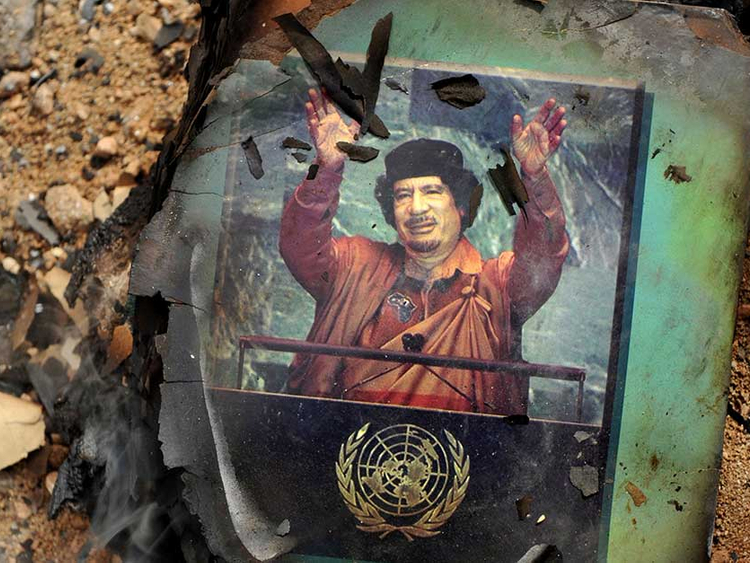

Tripoli: Four years after Muammar Gaddafi was killed in an uprising, the dictator’s legacy continues to haunt oil-rich Libya as it struggles to find its national identity.

“Gaddafi chose to build the idea of a state around his personality,” said Michael Nayebi-Oskoui, senior Middle East analyst at the US-based global intelligence firm Stratfor.

The dictator ousted and slain in October 2011, “used a military funded by oil to crush any opposition to himself, rather than build state institutions that could survive beyond him,” he said.

“It will be several years if not decades for Libya to create a national identity,” he said.

Libya, a largely tribal nation, descended into chaos after Gaddafi’s fall, with two governments vying for power and armed groups battling for control of its vast energy resources.

A militia alliance, including Islamists, overran Tripoli in August 2014, establishing a rival government and a parliament that forced the internationally recognised administration to flee to eastern Libya.

Months of UN-brokered talks to persuade the warring sides to agree to a peace deal and form a national unity government have run aground.

Taking advantage of the chaos, Daesh has gained a foothold in Libya and people-smugglers are again ferrying illegal migrants from its shores to Europe on rickety boats and contributing to thousands of deaths.

But the focus remains on Gaddafi, the flamboyant strongman who called himself “Guide of the Revolution” and declared Libya a Jamahiriya or “state of the masses” run by local committees.

“He will make headlines for a long time because the regime he consolidated will need a long time to be undone,” an official with the Tripoli-based government said.

“Everything he left behind is corrupted: politics, the economy, society even sports, and we need to change from A-to-Z, all the legislation, all the rules and all the instructions,” he added.

Gaddafi was captured and killed by gunmen in his hometown Sirte on October 20, 2011. Three days later transitional authorities announced the “total liberation” of Libya.

Known for his droning speeches and flashing bedouin-style robes, he ruled Libya four decades after leading a military coup that toppled a Western-backed monarchy in 1969. He died aged 69.

“There was no institutionalised state in Libya, leading to the chaos after his removal,” said Nayebi-Oskoui.

“He pitched tribes and regions and different ethnic groups against one another for decades, which is why Libyans and the international community have struggled to create a national identity in his absence.”

The expert believes that Gaddafi’s name and the consequences of his policies will continue to make news for years to come.

Last week Scottish prosecutors said they had identified two new Libyan suspects in the bombing of a Pan Am jet over the Scottish town of Lockerbie in 1988, which killed 270 people.

Scottish media named one of the two suspects as former intelligence chief Abdullah Sanussi and the other as Abu Agila Mas’ud.

Sanussi was sentenced to death in July for crimes committed during the uprising along with Saif Al Islam, Gaddafi’s son and one-time heir apparent, and seven other people linked to the slain strongman.

Mas’ud is reportedly behind bars in Libya, where Sanussi has been in custody since 2012.

Scottish prosecutors said they are suspects in the bombing along with former Libyan intelligence officer Abdul Baset Ali Mohmet Al Megrahi, the only other person ever convicted in the case who died in 2012 protesting his innocence.

Libya admitted responsibility for the bombing in 2003 and Gaddafi’s regime eventually paid $2.7 billion in compensation to victims’ families.

Gaddafi has left behind a “fractured nation,” said Nayebi-Oskoui, who expects that the policies he formulated would “extend for decades”.

The Tripoli government official agreed.

“He is still remembered despite his death and he will stay present among us until we can overcome the 40 years of chaos he has sown,” he said.

“I hope we won’t need another 40 years.”

Outside the walls of Gaddafi’s former Tripoli compound, meanwhile, street artists have left unflattering graffiti of the dictator and drawings, including one depicting him in a trash can.

“We used to be afraid even to look at the compound,” said Ahmad, a cigarette vendor who works nearby.

“Today, things have changed, of course, but the fear we felt still reminds us of him.

“Generations will pass before we can overcome the fear he instilled in us,” he added.