"I came over here because I wanted to kill people."

-Private First Class Steven Green, US Army; interview given to Washington Post reporter Andrew Tilghman; Iraq, February 2006

"I am truly sorry for what I did in Iraq and I am sorry for the pain my actions, and the actions of my co-defendants, have caused you and your family … I helped to destroy a family and end the lives of four of my fellow human beings …"

-Steven Green, ex-US Army; addressing the Al Janabi family in US Court, 2009

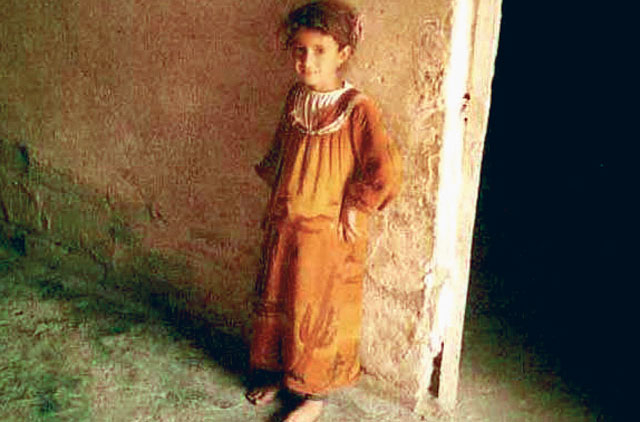

On March 12, 2006, Private First Class Steven Dale Green, along with three other American soldiers, entered the home of 14-year-old Abeer Qasim Hamzah Al Janabi in a village near Yusufiyah in Iraq, shot her family, raped Abeer in turns before shooting her and then set her body on fire.

The story of Abeer and her family's brutal murder and the kind of dysfunctional backdrop that led Green and his four comrades to commit one of the most heinous crimes in the history of the Iraq war forms the core of Black Hearts: One Platoon's Descent into Madness in Iraq's Triangle of Death by Jim Frederick, the newly appointed managing editor of Time.com and an executive editor of Time magazine.

The gripping narrative, however, reveals a deeper malady of modern warfare and sounds a timely warning about military leadership at a time when the US is exploring ways to extricate itself from two game-changing battles.

With the US on schedule for a planned drawdown to 50,000 troops by the end of this month before its ultimate exit from Iraq by the end of 2011 and the Wikileaks scandal catching White House on the wrong foot ahead of another planned drawdown in Afghanistan, military planners and defence analysts have scrambled to assess the impact both wars have had on their population and the US war machinery.

"The Iraq war was one of the most cataclysmic experiences in modern global geopolitics in a generation," says Frederick, who has held various senior editorial positions at Time prior to his present appointment and is also the co-author (with former US Army Sergeant Charles Jenkins) of The Reluctant Communist: My Desertion, Court Martial and Forty-Year Imprisonment in North Korea. "I decided there was so much more to the [Yusufiyah] story than just the crime and that it was really a story about the war in general … At a more detailed level, it's not just a story about a crime but a story about man at war," Frederick told Weekend Review in a telephone interview from London.

While the US political and military brass adapt to a theatre that's vastly different from the World Wars, the Cold War and the Korean or Cuban crisis, the combat zones of the 21st century keep springing challenges previously unacknowledged.

Consider, for instance, the improvised explosive device (IED), the nemesis of the infantry in the killing fields of Iraq. As Frederick describes in Black Hearts: "Every ride in a Humvee, every one, is an exercise in terror. You're riding, with your butt cheeks and fists clenched, doing deep breathing to control your heart rate and your nausea the whole time, waiting for it, waiting for it, waiting for it. And still, when it happens, it is the most surprising thing in the world … Depending on the size of the bomb and how closely it detonates, any combination of light, heat, pressure, dirt, fire, metal, wind and noise will hit you in a way your body can never be prepared for."

Suicide bombers, IEDs, hidden enemies and unmanned spy drones are stuff that post-9/11 wars are made of, rather than full-blown face-to-face combat. But providing genuine military leadership — down to the smallest squads and fire teams — in a situation where the troops are exhausted, overstretched and often bewildered by the logic of wars that change strategy and direction every season is possibly something that has never been a consistent priority.

General Stanley McChrystal, in his now infamous interview to Rolling Stones that sent him packing out of the US Army, was possibly being naively frank when he described what he told his men during a troop meeting in Afghanistan: "Strength is leading when you just don't want to lead … You're leading by example. That's what we do. Particularly when it's really, really hard, and it hurts inside."

McChrystal, who has since announced his retirement from the army, went on to tell the soldiers: "Winning hearts and minds in COIN [counter-insurgency] is a cold-blooded thing … The Russians killed one million Afghans and that didn't work."

With General David Petraeus — the architect of the revamped US Army/Marine Corps Counter-insurgency Field Manual — taking charge of the war in Afghanistan and General Ray Odierno continuing to oversee US troops in Iraq, the Obama administration has signalled its readiness to work on the complexities of Iraq and Afghanistan.

"The army and Marine Corps recognise that every insurgency is contextual and presents its own set of challenges. You cannot fight former Saddamists … the same way you would have fought the Viet Cong, Moros or Tupamaros; the application of principles and fundamentals to deal with each varies considerably," General Petraeus writes in the foreword to the manual. Indeed, a key part of applying those fundamentals is to narrow the gap between planning and encapsulating a military mission and achieving it: the gap between the ideal and the real.

Dr David Kilcullen, COIN theorist and adviser to General Petreaus in Iraq, was asked by the Washington Post about the lessons of Iraq that most apply to Afghanistan. "I would say there are three," he said. "The first one is that you've got to protect the population. Unless you make people feel safe, they won't be willing to engage in unarmed politics. The second lesson is you've got to focus on getting the population on your side and making them self-defending. And the third lesson is you've got to make a long-term commitment."

But, as Frederick argues, it's only through engagement and empathy between the top military leadership and the rank and file — the privates, sergeants, captains and so on — and the collective accountability for the success or failure of a mission that those lessons could come to fruition. Steven Green, for instance, arrived in Iraq in the summer of 2005 with the 1-502nd Infantry Regiment of the 101st Airborne Division. His battalion was assigned to the Triangle of Death — the 855-square-kilometre insurgent stronghold just south of Baghdad — to flush out insurgents, train the Iraqi army to defend itself and promote civic revival. "There was no coherent strategy for how they were supposed to accomplish these feats … This confusion flowed from the Pentagon, through the battalion's chain of command, all the way down to the soldiers," Frederick writes in the foreword to Black Hearts.

A deadly combination of poor or wrong strategy, the lack of proper leadership oversight, fatigue and stress from a below-par troop strength and the spectre of violence every minute, the constant threat of IEDs blowing up on them and the loss on average of a soldier every week then led the battalion into a downward spiral of demotivation and desensitisation: Some of them went high on drugs and alcohol; others sought refuge in a state of denial; a few scurried to the comfort of the Freedom Rest in Baghdad, a sort of army hotel that offered stress counselling, hot showers and gourmet food.

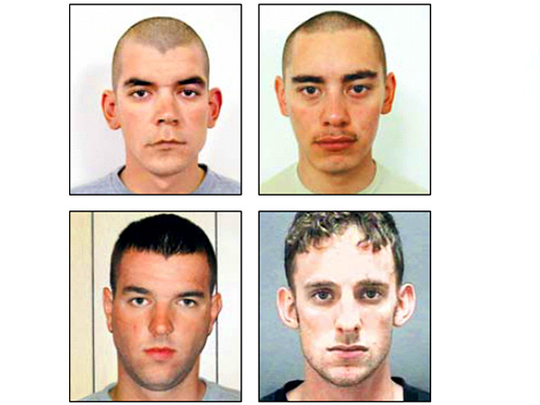

It was against this backdrop that on March 12, 2006, Private First Class Green, along with Specialist Paul Cortez, Specialist James Barker and Private First Class Jesse Spielman from the same platoon, abandoned the traffic checkpoint they were manning 32 kilometres south of Baghdad and headed to the farmhouse of Al Janabi set in a five-acre orchard that grew pomegranates, dates and grapes. Once inside, Green corralled Abeer's father, mother and 6-year-old sister in a room and shot them dead.

"I was hyped up, the adrenalin was really high," Green recalled later. "But as far as the actions of doing it, it's something I had been through a million times, in training for raiding houses. It was just eliminating targets and those were the targets that they [his compatriots in the mission] had told me to eliminate."

Green, Cortez and Barker then took turns in raping Abeer. Afterwards, they put a pillow on her face; Green took aim at the pillow and fired one shot that smashed her skull and instantly killed her. Before leaving, they set the girl's body on fire.

In a February 2006 interview with Andrew Tilghman, a correspondent of the US military newspaper Stars and Stripes who was embedded with the US army in Iraq, Green talked about killing Iraqis with similar disdain. "Over here, killing people is like squashing an ant. I mean, you kill somebody and it's like ‘All right, let's go get some pizza'."

The massacre of the Al Janabis in Yusufiyah is like a pattern that repeats itself in Haditha, Fallujah, Iskandariya, Hamdaniya and elsewhere in Iraq following the US invasion. Except that unlike, say, the Haditha massacre, where US Marines were accused of killing up to 24 civilians in retaliation for the death of a compatriot, the Yusufiyah rape and murders were premeditated acts of savagery: Green and his colleagues planned the assignment down to the last detail while playing cards on the morning of March 12.

"The great tragedy at the heart of the book is that even though it's about soldiers, the Al Janabi family, and by extension the entire Iraqi population, didn't ask for this war," Frederick said. "The Al Janabis haunt me far more than any of the American figures in the book do. But on the other hand, Steven Green is a very disturbing figure and I think about him a lot. If his life had gone a bit differently, if the war had gone a bit differently, he wouldn't have been sitting in jail today. Nobody's fated to become a criminal."

While Green was subsequently tried in a civilian court (he was discharged from the army before the crime was traced back to him) and sentenced to five consecutive life terms with no possibility of parole, his comrades in crime got various jail terms, all with the possibility of parole in 2016.

In the Iraq theatre, Green and the US troops behind the March massacre emerge as the archetypes of a war gone wrong. Along with the obvious individual culpability over the crime, it's also the intertwined context and responsibility of the whole military system that stand out as a stark reminder that in Iraq or Afghanistan or any other modern battlefield, it doesn't take too many wrong turns for something so abhorrent to happen.

"Clearly, a lot of what happened can be attributed to a leadership failure," says Captain Shawn Umbrell, Commander of the Headquarters and Headquarters Company (HHC) in the Black Heart Brigade. "And I'm not talking about just the platoon level. I'm talking about platoon, company, battalion. We were all part of the team. We just let it go … We failed those guys by letting them be out there without a plan."

Frederick agrees that it's leadership rather than personal morals or unflinching loyalty that ultimately decides the fate of an army unit at war. "Leadership is the most powerful factor in any military endeavour. So many soldiers fighting the wars [in Iraq and Afghanistan] are only 18 or 19 or 20. They'll do anything they are led to do. Just imagine what kind of trouble 18-year-olds go through in the civilian world. If there's a vacuum in military leadership and they are left to defend themselves, think what they could be capable of."

An acute shortage of troops as the US grapples with two wars has combined with the often-lacking leadership to create a no-win situation that Frederick describes.

Rolling Stones reporter Michael Hastings, who interviewed General McChrystal, provides a barometer of battle morale in Afghanistan when he says that the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) has been dubbed "In Sandals and Flip-Flops" by US soldiers engaged there. Many of the new army or Marine recruits are also a by-product of America's aggressive troop-recruitment strategy, rather than an overwhelming inclination for military life.

Steven Green, in his conversation with Tilghman of Stars and Stripes (now a reporter for the Washington Post) just weeks before the murder of Abeer, is brutally honest: "I gotta be here for a year and there ain't [expletive] I can do about it … I just want to go home alive. I don't give a [expletive] about the whole Iraq thing. I don't care." Green's equally brutal about the motivation (or lack of) from his higher-ups: "We're pawns for the [expletive] politicians, for people who don't give a [expletive] about us and don't know anything about what it's like to be out here on the line."

Perhaps a reflection of the new realities — the feeling of being left alone to fight your own battle against an unknown enemy, the trauma of coping with near-violence all the time — lies in the statistics of US troop suicides released in July.

Army data show a record number of suicides in one month among active duty, Guard and Reserve troops, despite an aggressive programme of counselling, training and education aimed at suicide prevention.

According to the Associated Press, suicides in the first half of the year went up 12 per cent over 2009. In June, 32 soldiers in Iraq, Afghanistan and elsewhere were believed to have committed suicide, including 21 on active duty. In 2009, 52 Marines and 48 sailors also took their own lives, according to a report by the American Forces Press Service, while Air Force officials reported 41 active-duty suicides.

"After Iraq, we may be tempted to turn inward. That would be a mistake. The American moment is not over but it must be seized anew," Barack Obama, then a senator, said in an article titled Renewing American Leadership in 2007. "We must bring the war to a responsible end and then renew our leadership — military, diplomatic, moral — to confront new threats and capitalise on new opportunities," he wrote.

Trying to turn that speech into a reality and often faltering along the way, Obama will perhaps be able to ensure that not only is another Abeer never butchered again but also that another Steven Dale Green never boasts in battlefield that he came to kill Iraqis and then stands trial, facing possible execution for killing them.

Until then, the battle theatres of Iraq and Afghanistan will continue to be disasters waiting to happen.