Arbil, Iraq: The battle plans to oust Daesh from the city of Mosul are in place, but an uneasy mix of forces fighting against the terrorists could delay the fight or ignite separate conflicts.

Preparations for the offensive have sped up in recent weeks, after officials in Baghdad and the Kurdish regional government agreed on a detailed military plan to retake the northern city. But thornier issues are still being worked out, such as the role of Iraq’s Shiite militias and the question of who will control the land after it is retaken.

The battle for Iraq’s third-largest city will be the biggest yet by Iraqi forces, who are backed by the US-led coalition. The city, home to more than a million people, is Daesh’s last major stronghold in the country.

For Iraqi authorities, it’s a careful balancing act. Mosul and the surrounding province of Nineveh are in one of the most religiously and ethnically diverse areas of the country. Though in theory united against a common enemy, many of the groups jostling for a role in the fight are bitter rivals with competing interests.

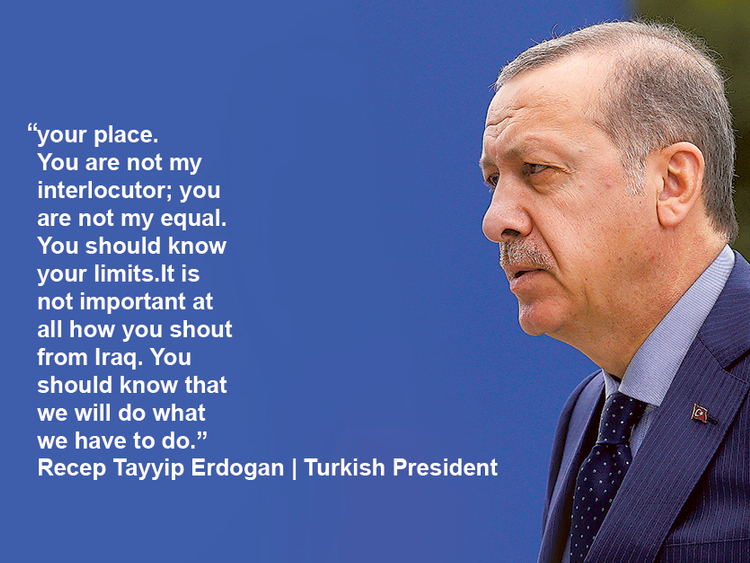

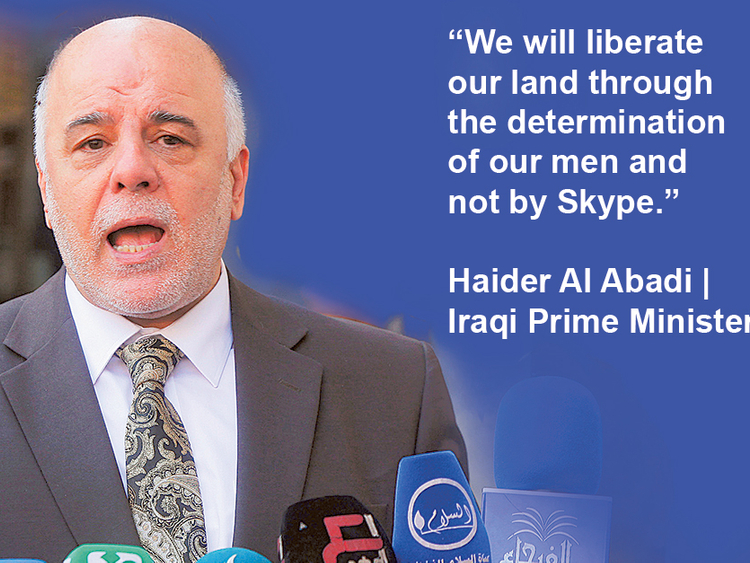

Meanwhile, neighbouring Turkey, which has historic claims to Mosul, is also publicly insisting on playing a role despite vehement objections from Iraq.

Prime Minister Haider Al Abadi has accused Turkey, which has troops in Iraq against Baghdad’s wishes and has been training Sunni fighters for the assault, of risking a “regional war” by attempting to interfere in the offensive.

“The situation is extremely difficult in Mosul,” said Iraqi government spokesman Sa’ad Al Hadithi. “We need to ensure a cohesion and make sure all the sectarian and ethnic worries are addressed.”

Under the military agreement, which lays out the plan of attack, only Iraqi special forces, army, police and volunteer fighters from the area will be allowed to enter the city, according to Iraqi military spokesman Lt Gen Yahya Rasoul. Iraqi troops will be allowed to move through and build up a presence in areas controlled by Kurdistan’s semi-autonomous government, and sectors of the battlefield have been assigned to various Iraqi forces.

The role of the Shiite militias is “still to be determined”, Rasoul said, though they may be used to secure the outskirts of the city.

Tensions over power and land have already caused factions fighting Daesh in Iraq to turn their weapons on each other. Shiite militias have clashed with Kurdish peshmerga forces over the past year in the northern town of Tuz Khurmatu.

Jawad Al Tleibawi, a spokesman for Asaib Ahl Al Haq, one of Iraq’s main Shiite militias, said his group will prevent “Kurdish greed” during the offensive and its theft of Iraq’s land. Shiite militias have mushroomed over the past two and a half years, since a call to arms to plug the gap after the Iraqi army collapsed in Mosul and Daesh pushed toward Baghdad.

Al Tleibawi said it is his militia’s “national and religious duty” to take part in the battle for Mosul. He also said that Turkish troops, and fighters trained by them, will be treated as an “occupying force” if they were allowed on to the battlefield.

Iraqi officials have repeatedly demanded that Turkey withdraw its forces, which remain on a base in northern Iraq and have provided artillery support to Sunni fighters battling Daesh.

“No one can prevent us from participating,” Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan recently said of the Mosul offensive. Erdogan has said Turkey has a duty to protect ethnic Turkmen in the area because of their close cultural ties.

Iraqi officials and analysts say one of the most dangerous potential flashpoints is in the town of Tal Afar, 70km west of Mosul, which gave birth to many of Daesh’s top leaders. It is home to ethnic Turkmens — Sunni and Shiite.

Shiite militia leaders say they should play a role in Tal Afar because of the significant Shiite minority there. But any revenge killings against the Sunni majority could provoke Turkish forces to intervene.

“We think it’s better to keep [Shiite militias] out of Tal Afar; it’s a bad idea to have them there,” said Atheel Nujaifi, the former governor of Nineveh province, whose Sunni fighters are being trained by Turkey. “We are trying to do that politically because we can’t prevent them by force.”

Adding to the complications, Turkey has also strongly objected to any involvement by the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, or PKK, which also has forces in Iraq fighting Daesh. The PKK has publicly stated that it wants to be involved. Assyrian Christians and Yazidis also have their own armed militias in the area.

Given the potential for conflict after Daesh is ousted, some Iraqi officials argue that issues of how the area will be governed and stabilised must be addressed before the offensive begins.

“If they don’t take a decision on what to do after, that means they’ll leave it up to whatever de facto situation happens on the ground,” Nujaifi said. “And that will lead to a struggle.”

But what happens to land that Kurdish forces recapture is still unclear. Kurdish officials have indicated that Kurdistan will keep any land taken by its forces during the offensive. Meanwhile, Al Hadithi contends that “there will be no change in status of territory due to military operations”.

Iraqi military commanders say the planning stage is over and that it’s only a matter of weeks before an offensive is launched. Al Abadi has pledged to retake Mosul by the end of the year.