Algiers: These are challenging times for North Africa’s governments. Even as Daesh is ousted from its strongholds in Iraq and Syria, the extremist group is continuing its battle against authorities in countries like Morocco, Algeria and Egypt.

On Oct. 16, the Egyptian military announced that six soldiers and at least 24 Daesh militants were killed in attacks on military outposts in North Sinai. That same weekend, Moroccan police arrested 11 members of an “extremely dangerous” Daesh-linked cell and seized chemical products used to make bombs.

Algerian forces, meanwhile, have killed at least 71 Islamist fighters so far this year — the most since 2014.

The list of arrests, shoot-outs and seizure of passports from citizens who want to be foreign fighters goes on. But North African leaders have to navigate a particularly tortuous sectarian path. To avoid the perception that fighting extremism amounts to the persecution of Sunnis, their governments have to be seen to be making visible gestures of Islamic piety — while also cracking down on Shiite proselytising so as to rebut Daesh claims that authorities are complicit with Iran’s “plots and schemes” to carve up the region and spread Shiite Islam.

The Islamist PJD party in Morocco warned recently of a “sectarian Shiite invasion”; the Grand Mufti of Mauritania called on his country’s leaders to resist the “rising Shiite tide.”

One North African government minister denounced “the intrusion of Shi’ism through social media, university dormitories, high schools and even qur’anic schools,” concluding gravely, “I ask myself whether the Persians want to dominate the Arab world.”

After Iraq, Yemen, Syria, Lebanon and Bahrain, is North Africa the next realm of a more assertive Iranian foreign policy? These fears come from Iran’s attempt to expand its influence in Algeria, Mauritania, Morocco, Tunisia — and its “backyard:” Senegal, Niger, Guinea and Mali.

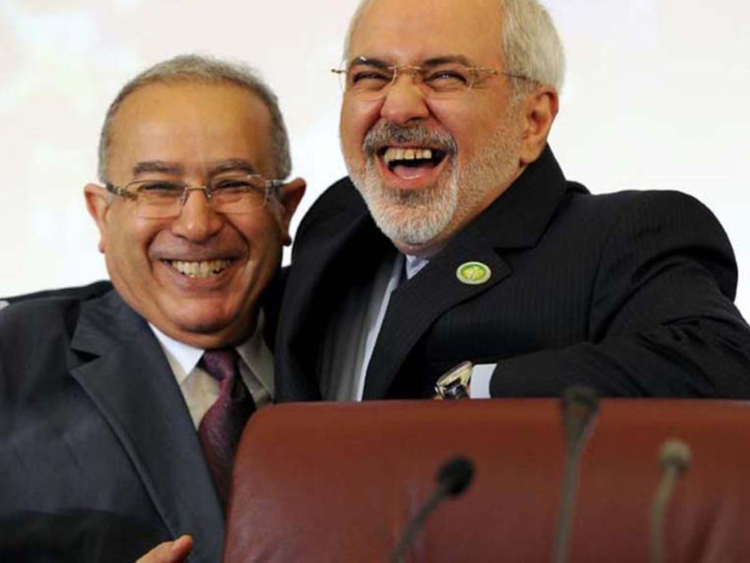

Iran’s foreign minister toured the region in June, meeting with heads of government in Algeria, Mauritania and Tunisia in search of improved ties. Iran may simply be looking for new economic partnerships to offset current sanctions, but its outreach is enough to make some local powers nervous.

Around the same time, Iran launched satellites beaming Arabic-language Shiite religious programming into North African homes.

There are thought to be fewer than 20,000 Shiites in Algeria, and the government recently mandated the registration of all of them.

The Algerian minister of religious affairs has said that Shiites have no right to spread their faith in Algeria, “because that causes sedition and other problems.”

“Algeria cannot play host to a sectarian war that does not concern it,” he explained in an interview.

“Neither Shi’ism, nor Wahhabism nor any of the other sects are the product of Algerians, nor do they come from Algeria. We refuse to be the battleground for two external and foreign ideologies.”

Diplomatic relations resist easy categories, however.

Algeria is one of only a handful of countries to maintain relations with Yemen’s Iran-backed Al Houthi rebels.

Algiers was Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif’s first stop in North Africa in June.

Given the tiny number of Shiites living in North Africa and the tight control over mosques in the region, widespread Shiite religious influence on the ground is unrealistic.

Whether or not the scale of proselytism justifies the level of concern, Moroccan and Algerian leaders view Iran’s Africa policy as a threat to their domestic order and regional security. The prospect of sectarian strife exists for “heterodox” — i.e. non-Sunni — minorities scattered across the region, numbering in the millions who live under mainstream Sunni rule.

Some of these groups are offshoots of Shiite Islam, but are not necessarily the source of conflict.

In Algeria, their mere difference — and the government’s toleration of them — sometimes provokes attack from local hardliners.

North Africa’s Sunni governments struggle with the reality that two adversaries — Iran and Daesh — are the net beneficiaries of the invasion of Iraq in 2003 and the crushing of Sunni opposition in Syria in 2017.

The downfall of Sunni Baathist rule in Iraq enhanced Iran’s stature while diminishing Sunni Arab influence in Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria — and opening a path for Daesh.

Officially, there is no Shiite minority in Morocco; unofficial estimates put the number at less than 2 per cent.

Nonetheless, the foreign ministry in Rabat has accused Iran of trying to alter “the kingdom’s religious fundamentals.”

The bad blood is the legacy of a sour relationship between Ayatollah Khomenei and King Hassan II (the father of current Moroccan King Mohammed VI) in the 1980s.

The Ayatollah’s claims of Islamic supremacy over all Muslims threatened the Moroccan King’s role as “Emir Al Mumineen” — leader of the faithful — of scores of millions of followers across Northwest Africa.

Hassan chaired the international council of Islamic scholars that declared the Ayatollah to be an apostate — “if he is Muslim, then I’m not” — and openly supported Iraq in its war with Iran.

In turn, Hassan thought he saw an Iranian hand behind his domestic travails. Tehran provided safe haven to the Moroccan armed opposition group Chabiba Islamiya, and Hassan publicly accused Iran of fomenting riots against rising living costs and the violent uprising in the northern Rif region that is home to many Berbers.

Street contestation in the Rif region has again put Rabat off balance in 2017 and revived the accusations a generation later.

The contrast with neighbouring Tunisia is significant.

Tunis has enjoyed unbroken relations with Iran since 1990, including high-level exchanges before and after the January, 2011 revolution that sparked what became known as the Arab Spring.

Trade with Iran increased significantly as a result, but hardly registered compared to much more significant trade with the EU, North Africa, China and Turkey.

Tunisia prides itself on being an island of sectarian tolerance in a rapidly polarising region.

Senior religious affairs officials proudly state that they represent all religions, including Christians and Jews, although in reality the country has very few non-Sunni Muslims.

After the January 15 revolution, Tunisia signed the United Nations Convention on Human Rights and helped protect religious freedom in Article 6 of its new constitution.

Saudi Arabia has maintained its natural advantage, however.

A month after the Iranian foreign minister left Tunis, a Saudi government delegation arrived, including 53 businessmen.

They signed agreements with the government worth $200 million in development projects, including several hospitals and the renovations of a historic mosque in Kairouan.