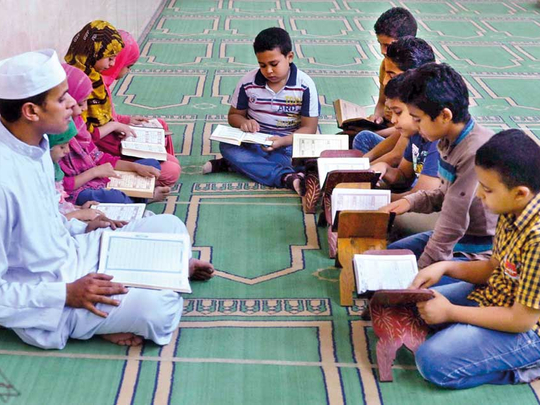

Cairo: Having led the faithful in the afternoon Muslim prayer at a local mosque, Abdul Tawab Mahjoub gets ready for another daily task. A flock of little children wait for him in a corner of the mosque in northern Cairo. Each holds a copy of the Quran, Islam’s holy book.

Clad in a flowing garment and a cap, the 41-year-old man squats. Boys and girls gather around him. They attentively listen to the cleric and repeat after him.

Since May this summer, Shaikh Abdul Tawab, as he is known among his little pupils, have been teaching the children how to correctly recite the Quran and learn some of its chapters by heart.

He also teaches them how to perform ablutions, a ritual that Muslims do before they carry out daily prayers.

“Since the mosque administration announced holding a free course for teaching the Quran, many parents in the district have been interested in registering the names of their children in this course that is held daily from after the afternoon prayer until the sunset,” Abdul Tawab says.

“Apparently with encouragement from their families, many children have been punctual and shown good skills in memorising some chapters suitable for their ages.”

The course is open to children aged from six to 12 years. It is part of a plan launched by the Ministry of Waqfs (religious affairs), which is responsible for mosques in Egypt, to fight militancy among youngsters.

Abdul Tawab takes care of explaining meanings of the Quranic verses, using simple words.

“I explain to the children ethics in Islam and give them examples from the lofty Sunna (teachings) of Prophet Mohammad (PBUH), highlighting his mercy and forgiveness towards others,” Abdul Tawab told Gulf News.

“The problem with many preachers nowadays is that they do not emphasise the boundless mercy found in Islam and its openness to followers of other religions. These preachers tend to focus on the Hell in the Hereafter and spread hatred against others, giving the erroneous impression that Islam is a rigid and violent religion,” adds Abdul Tawab, who studied years ago at Al Azhar, Egypt’s prestigious Sunni Islamic centre of learning.

Egyptian authorities in this mostly Muslim country have tightened control on mosques since the army’s 2013 overthrow of Islamist president Mohammad Mursi following mass protests against his divisive rule.

The government has since brought thousands of mosques across the country under its grip, denying Mursi’s Muslim Brotherhood and allied groups a major forum to influence devout Muslims.

In recent months, religious authorities have cracked down on privately operated Quran schools and tightened rules for licensing them in order to ensure they are not indoctrinating children with radical ideas.

Teachers at these schools are required to memorise the Quran and master rules of its recitation. They should also have no links to extremist groups, including the Brotherhood, which is outlawed in Egypt.

Dozens of schools with suspected ties to the Brotherhood have been brought under state control since Mursi’s ouster.

“Incidents of recent years in Egypt and other countries of the region prove that educating people about the true teachings of Islam is a vital matter that should not be left for individuals or groups, who pursue alien goals,” says Abdul Tawab.

Extremists, including Daesh terrorists, have plunged the Arab region into destructive turbulence and committed mass abuses against religious minorities and fellow Muslims.

“New interest in Quran-memorisation schools is a step in the right direction to groom a generation of children, who are familiar with the genuine principles of Islam,” Abdul Tawab adds. “It is also a revival of an intrinsic Egyptian legacy.”

Locally known as Katateeb, Quran schools are believed to have emerged in Egypt in the middle ages and thrived in modern eras, mainly in rural areas.

They were an effective tool in preserving the Arabic language under the British colonial occupation of Egypt from 1882 to 1954.

Several of Egypt’s big names in different fields attended these schools, which also used to teach basic rules of reading and maths in return for some fees.

But these schools have lost their attraction in Egypt in recent decades with the emergence of Western-style kindergartens.

“Unlike Sayedna [the Quran teacher] in the old Kutab, I don’t have a cane or a whip to punish the lazy children,” says Abdul Tawab with a grin. “I encourage pupils to learn from their mistakes. I also try to provide the group with a competitive environment of learning. The brilliant ones will be honoured at the end of the course.”

Reviving the Quran schools is a reason of joy for some children attending Abdul Tawab’s course.

“Shaikh Abdul Tawab has taught us how to perform ablutions and pray correctly,” says Marawan Ahmad.

“My father and mother did not have time to teach me how to do them. Shaikh Abdul Tawab always tells us that Islam is a religion of mercy and peace and that we should respect the old and be kind to the young because these are the morals of Islam,” the eight-year-old boy adds.

There are around 2,500 Quran schools under state supervision in Egypt.

Egyptian President Abdul Fattah Al Sissi has repeatedly called on the country’s Muslim scholars to reform the religious discourse in order to help confront violent radicalism.