Abu Dhabi: When the world thinks of Algeria, a few things come to mind: a long and violent war for independence, the vast oil and gas reserves of the Sahara, football superstars of Algerian origin, and, maybe most popularly, the trumpeting sounds of Raï music. While few know its origins, during the wedding season, millions of Arabs are heard belting verbatim Khaled’s Abdelkader or Rachid Taha’s remake of ‘Ya Rayah’.

Khaled Abdel Kader’s 2012 hit single, ‘C’est La Vie’, was streamed 95 million times on YouTube.

Khaled Abdel Kader’s 2012 hit single, ‘C’est La Vie’, was streamed 95 million times on YouTube.

For many musicologists and historians, Raï is rebel music. It is the soundtrack of artists who fought social stereotypes and religious conservatism to express love, desires, and an alternative world for youth. It is the melody of the musical subaltern; a compendium of artists whose sound differs in every which way except for the fact that they are not from the West (this genre is also marketed as world music). To explore this hypothesis, we return to the ground zero of Raï -- Oran (Wahran), Algeria.

The origins of Raï

Raï was conceived from a collection of different genres that were popular in the towns and villages surrounding Oran. Prior to its independence, Algeria was populated and occupied by people from diverse backgrounds. Music was influenced from a history of intermingling between Spaniards, Jews, French, Africans, and Arabs.

Raï, which literally means opinion, began to take shape in the 1930s when traditional Arab poetry, long used to pay homage to religious figures, began to recited musically in the less fortunate neighborhoods of Oran. Poets or Chuyukh (plural of Cheikh, a religious leader or learned man), as they were known on the streets, expressed their Raï (opinions) on social issues and inequalities between Arabs and French occupiers.

By the 1940s and 50s, these diatribes became anthems for the colonized. They were increasingly heard in Socialist and Marxist groups demanding the exit of the French. As political manifestos spread so were the musical influences of other anti-colonial movements. Wahrani, the seed of modern Raï music, began to mix poetic diatribes with Andalussian and Egyptian sounds. Simultaneously, the Cheikh, an homage to Raï’s religious origins, became the Cheb (young man). But it was not a young man that is credited as being the point of origin.

The Queen of Raï

Born Saadia (meaning joyful), Cheikha Remitti is the Queen of Raï. Orphaned at a young age, she worked odd jobs, learning to sing at wedding parties for a troupe of musicians. She was one of the first women to sing to mixed audiences denigrating the occupiers and the general misery of the Algerian people.

“I sang all the subjects back then,” she told Afropop Worldwide in 2001. “I sang about misery. I sang about love. I sang about the condition of women. I sang about ordinary life, concrete things. I sang the life I had seen, my own history.”

Cheikha Rimitti, is known as the Queen of Raï music.

Cheikha Rimitti, is known as the Queen of Raï music.

Although she composed hundreds of songs, Cheikha Rimitti (a reference to the French verb remettez or ‘top me up’) was illiterate. “Words sing silent in my head until I sing them loud,” she once said. “No need to take either a pencil or a notebook.”

The rebellious streak undoubtedly began with her. One of her first recordings, which touched on the virtue of young women, caused national controversy. When Algerian independence was achieved in 1962, her music was banned from national airwaves but her words reverberated in underground cabarets and gatherings.

Young and Brash Voices

During the 1970s and 1980s, Algeria was developing a post-colonial identity and an independent political paradigm. Islamists, socialists, marxists, and neo-liberalists were all fighting to occupy the hearts and minds of the populace. Raï was the musical experiment for the creatives and the outlet for youth starving to find their place between these diverging philosophies.

From Cheikha Remitti’s brashness emerged a class of courageous young Algerian musicians. Banned by President Houari Boumedienne, Raï singers openly criticised the young regime’s failure to fix social and economic issues. And, in opposition to increasingly militant strands of Islamism, they also attacked social and religious taboos on marriage, love, alcohol, and music.

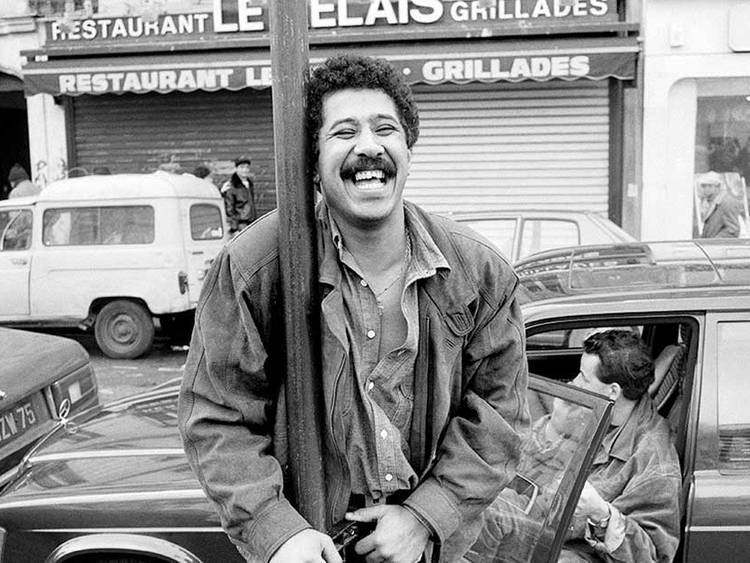

Cheb Hasni, a musical martyr, was a child of that generation. To this day his face is memorialised on the graffitied walls of Algerian casbahs. A singer with a powerful voice, Hasni was front and center on the music scene and a rebel to his death. Against the advice of his parents and like the Queen herself, Hasni sang at wedding parties and his popularity spread across the entire Maghreb and France. His cassettes spread like wildfire.

Cheb Hasni

Cheb Hasni

His death came at the height of the Algerian civil war, as the regime was fighting an Islamist insurgency that brutally targeted musicians, journalists, artists, lawyers, judges and authors for their symbolic value. In September 1994, despite innumerable public threats against his life, Hasni returned to his neighborhood of Gambetta in Oran to stay close to his public and his origins. He was killed on the ground floor of his parent’s apartment building.

Raï, the World’s Music

In the late 1980s, with Islamists taking a strong stance against Raï, the Algerian government decided to reverse its ban. Its first move was to finance a studio album by a then-young artist named Cheb Khaled. A concert was also co-organised between the French and Algerian government in 1988 at Bercy. This concert and that album, Kutché, are tributed as the genesis of modern Raï with expertly studio-produced albums and sound-engineered voices.

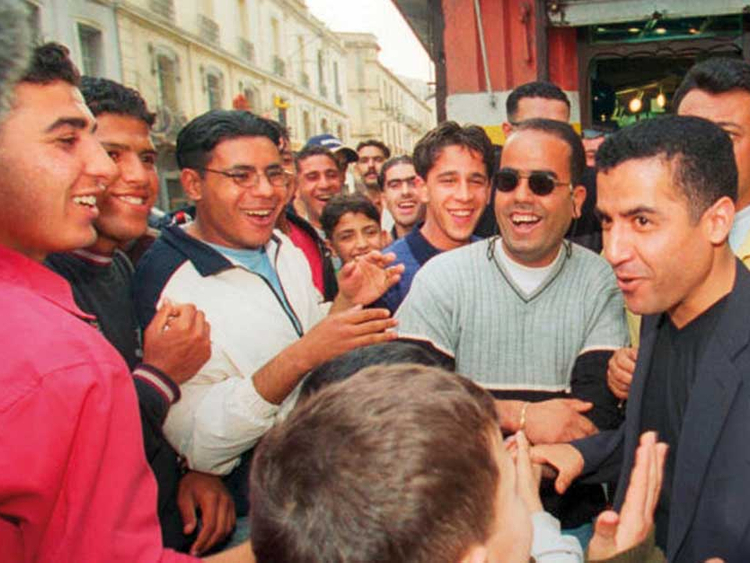

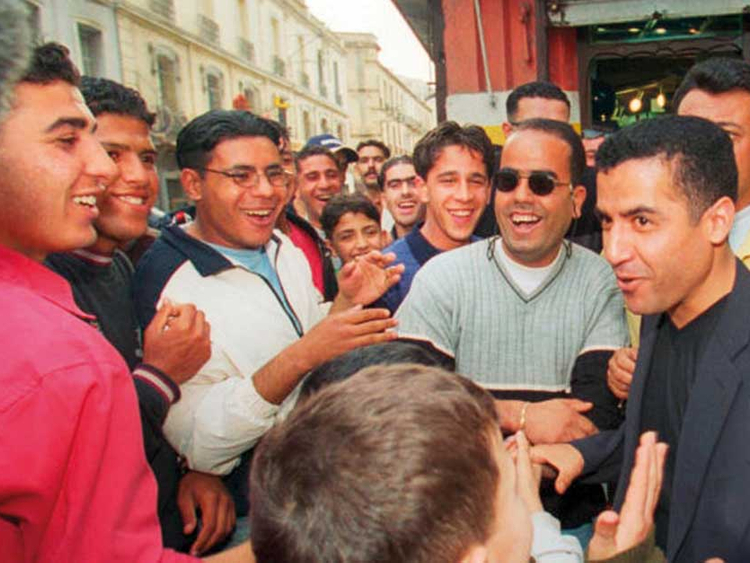

With their lives threatened in Algeria, the Raï musicians of the 1990s were found in Paris and London, and their sound transfixed audiences worldwide. Two men stood out above the fray and their albums were selling in the millions. By the late 1990s and into the 2000s, Cheb Khaled (or Khaled as he is now known) and Cheb Mami were touring the world selling out shows in Tokyo and Los Angeles, and showcased on US late night talk shows or the Superbowl.

Cheb Khaled

Cheb Khaled

Today, their music, although not as edgy or daring as it once was, continues to be played by the million. Khaled’s 2012 hit single, ‘C’est La Vie’, was streamed 95 millions times on YouTube and he was the headlining Arab artist for Abu Dhabi’s Formula One concert in 2015.

Nevertheless, these hugely successful and rich artists, continue to live in the shadows of their predecessors. In Algiers, Cheb Hasni always takes the cake, and, in the history books, it is Cheikha Remitti that will be marked as the Queen of Raï.

She sang daringly and forthrightly about sexuality, poverty, drinking, oppression and independence. “Misfortune is my teacher,” she often said. “Raï music has always been a music of rebellion, a music that looks ahead,” she said in 2001.

Cheikha Remitti died in 2006 at the tender age of 83. A rebel to death itself, two nights before her death, Remitti was performing at the Zénith concert hall in Paris.

-Tarik Chelali is an independent analyst on North Africa. This article is adapted from a presentation given to the Afikra community.