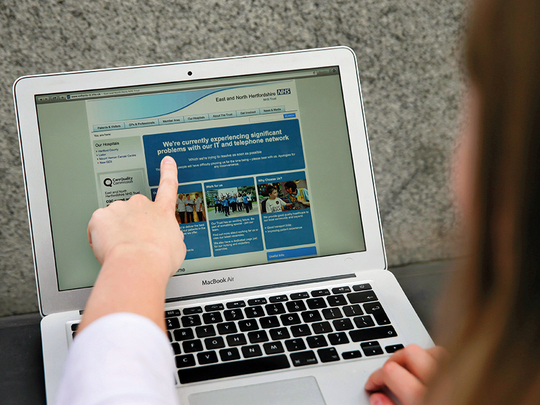

LONDON: Britain’s National Health Service ignored numerous warnings over the last year that many of its computer systems were outdated and unprotected from the type of devastating cyberattack it suffered Friday.

The attack caused some hospitals to stop accepting patients, doctor’s offices to shut down, emergency rooms to divert patients, and critical operations to be cancelled as a decentralised system struggled to cope.

At some hospitals, nurses could not even print out name tags for newborn babies. At the Royal London Hospital, in East London, George Popescu, a 23-year-old hotel cook, showed up with a forehead injury. “My head is pounding and they say they can’t see me,” he said. “They said their computers weren’t working. You don’t expect this in a big city like London.”

In a statement on Friday, the NHS said its inquiry into the attack was in its early phases but that “at this stage we do not have any evidence that patient data has been accessed”.

Many of the NHS computers still run Windows XP, an out-of-date software that no longer gets security updates from its maker, Microsoft. A government contract with Microsoft to update the software for the NHS expired two years ago.

Microsoft discontinued the security updates for Windows XP in 2014. It made a patch, or fix, available in newer versions of Windows for the flaws that were exploited in Friday’s cyberattacks. But the health service does not seem to have installed either the newer version of Windows or the patch.

“Historically, we’ve known that NHS uses computers running old versions of Windows that Microsoft itself no longer supports and says is a security risk,” said Graham Cluley, a cybersecurity expert in Oxford, England. “And even on the newest computers, they would have needed to apply the patch released in March. Clearly that did not happen, or the malware wouldn’t have spread this fast.”

Just this month, a parliamentary research briefing noted that cyberattacks were viewed as one of the top threats facing Britain. The push to make medical records systems more interconnected might also make the system more vulnerable to attack. Britain plans to digitise all patient records by 2020.

Several news reports have addressed the outdated systems of the NHS that potentially left confidential patient data vulnerable to attack. In November, Sky News did an investigation showing that units of the NHS, serving more than 2 million people, spent nothing on cybersecurity in 2015. Jennifer Arcuri, of Hacker House, which worked with Sky on the report, said then: “I would have to say that the security across the board was weak for many factors.”

On Friday, Arcuri said on Twitter: “We told every [one] back in Nov this would happen! @myhackerhouse identified NHS trusts putting patient data at risk.”

The NHS, founded after Second World War, employs 1.6 million people with a combined budget of £140 billion (Dh662 billion), making it one of the largest employers in the world.

But its budget is always under pressure and the Conservatives, while increasing funding, have been sharply criticised by opposition parties for not devoting enough resources for new, more expensive treatments and to cope with an ageing population.

As the attack unfolded on Friday, NHS officials struggled to get a handle on the problem, but urged patients who had emergencies to go to hospitals or seek care as they normally would.

At St. Bartholomew’s, a sprawling hospital in London’s financial centre, non-essential appointments and surgeries were cancelled. Some ambulances were diverted to other hospitals.

One surgical resident, who declined to give his name because he was not authorised to speak to journalists, said he was in the middle of a heart operation around lunchtime when several computers suddenly flickered off, although monitoring equipment remained operational. He said his group was able to safely perform surgery.

He said the hospital had cancelled any noncritical operations because of the difficulty of getting into patient medical records, but that patient safety was not at risk.

Esther Rainbow, a manager of cardiac services at the Barts unit of the NHS in London, said in an interview that in coping with the attack, the hospitals had to use older systems involving patient notes on paper. “Pretty much everything now is electronic,” she said. “Each patient has a folder of notes, but we’re doing that less and less. So had to revert to the older paper note system.”

Prescriptions for pharmacies, which are normally ordered online, had to be written on paper, too, she said.

The hospitals also struggled with some heart scanning machines that feed into the computer network, and had to shut those down, she said.

“For us the main issue has been getting information,” she said. “At Barts, we were told not to use our work mobiles and to turn off all WiFi. Later in the day we were told to unplug everything from the network. The main impact in terms of the diagnostics was that we had no idea who was turning up and which patient was seeing which unit.”

“As the day went on it felt a little bit more scary,” Rainbow added, “as we were told to shut things down and unplug things. We also don’t know what other patients are due to come in. There may be a knock-on effect for Monday and Tuesday.”