Calais, France: Dozens of refugee youths were left fending for themselves on Friday after a second night sleeping rough in the Calais “Jungle” as France and Britain battled over who was to blame for their plight.

Around 100 teenagers and young men slept in some of the shelters left standing in a part of the slum that was razed in March, a prelude to this week’s massive clearance of the camp.

Some bedded down in a makeshift church, others in a mosque, according to the Care 4 Calais charity, which said it expected the authorities to lay on buses to take them to children’s shelters.

The fate of minors left behind in the blackened mess of the sprawling camp emptied of thousands of refugees this week, some of whom set fire to their shelters on leaving, has sparked a war of words between France and Britain.

France sees the “Jungle” — one of the most visible symbols of Europe’s refugee crisis — as a problem of Britain’s making given that most of the asylum seekers living there hoped to smuggle across the Channel into England.

On Thursday evening, French Interior Minister Bernard Cazeneuve reacted indignantly to a demand by his British counterpart, Amber Rudd, that children left in the Jungle “be properly protected.”

In a joint statement with Housing Minister Emmanuelle Cosse, Cazeneuve expressed “surprise” at Rudd’s call.

“These people ... had been planning to migrate to the United Kingdom”, the ministers said, insisting that France “had fulfilled its responsibilities out of solidarity and without trying to shy away [from its duty].”

Nearly 1,500 children have been moved to a container camp reserved for minors next to the Jungle. Britain has taken in 274 others since mid-October and is examining hundreds of other applications.

On Thursday, eight more buses left from the slum that has become a ghost town, carrying 226 adults and 16 minors to far-flung shelters.

A spokesman for the United Nations (UN) children’s agency, UNHCR, said on Friday the agency had asked that “special arrangements be made to ensure the safety and welfare of children in the Jungle”, before it closed.

“We are continuing to work to identify and protect children and other individuals with special needs in Calais,” spokesman William Spindler said in an emailed statement.

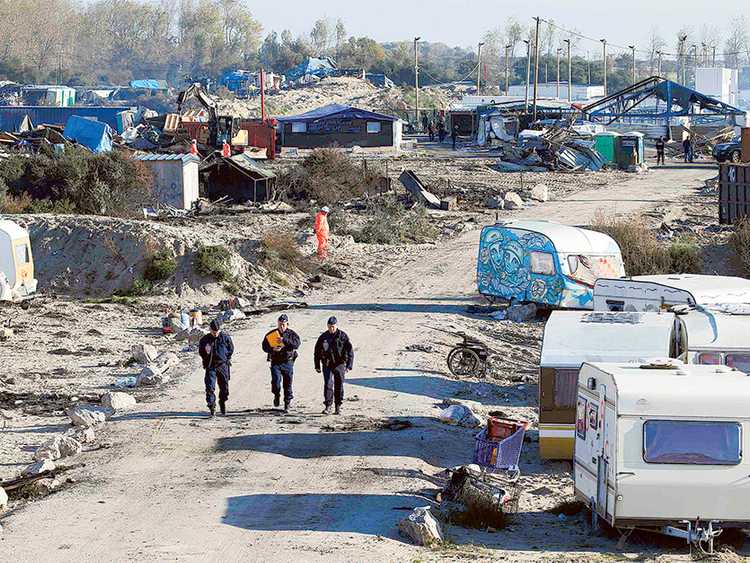

On Friday, demolition teams resumed tearing down the makeshift dwellings where around 6,400 people, mostly Afghans, Sudanese and Eritreans, had been living according to official estimates.

‘Serious obligation’

Nearly 4,400 adults, mostly single men, have been moved to towns and villages around France.

Regional security chief Fabienne Buccio declared the camp empty on Wednesday after nearly all the refugees had been bussed away and claimed those left on Thursday were new arrivals.

“You can’t say the operation is over when there are people left,” said Anne-Louise Coury, angrily, the Doctors Without Borders (MSF) coordinator in Calais. “The state still has a serious obligation towards migrants who are minors.”

In sections that had yet to be razed, youths and charity workers huddled around coal fires Thursday evening.

A giant teddy bear lay face down in the sand and flowers still sprouted from planters, a reminder of a community that had tried to preserve basic pleasures while living in transit.

More than one million people fleeing war and poverty in the Middle East, Asia and Africa poured into Europe last year, sowing divisions across the 28-nation bloc and fuelling the rise of far-right movements, including Germany’s Pegida and France’s National Front.

Most of the refugees in Calais hoped to reach Britain because they have contacts there, speak the language and believe their job prospects to be better than in France.

Aid groups estimated that between 2,000 and 3,000 refugees still intent on crossing the Channel left the Jungle before the evacuation began, some of them fleeing south to Paris.

Charles Drane, coordinator of an NGO that helps asylum seekers sleeping rough in northeast Paris said his charity was now feeding over 1,000 people a day, up from 700-800 a few days ago.

French authorities has those who agree to be moved to shelters can seek asylum in France. Those who refuse risk being detained and deported.

Many locals fear new settlements will simply spring up in the area after the Jungle is razed.

Calais Mayor Natacha Bouchart said claims of the Jungle’s demise were “premature” and demanded “guarantees” that it would not spring up again, once the police had left.