ISLAMABAD

Saeed Hamid’s restaurant is covered with touristic murals from Afghanistan — blue-tiled shrines and aqua lakes, ancient Buddhas carved into cliffs, and an enormous scene of horses and riders scrimmaging on a muddy field, trying to capture the carcass of a goat.

Hamid’s nostalgia stops right there. His parents fled their conflicted homeland before he was born, and he grew up in Pakistan’s capital. He learnt English, married and raised his own children here, and built a flourishing bakery and kebab house that employs 20 people and is packed every evening.

So it is easy to understand his anxiety about the future. In the past year, more than 250,000 undocumented Afghan refugees have returned to their impoverished, insurgent-plagued country under pressure from Pakistani auth-orities.

Now the population of 1.5 million long-settled, registered refugees has been given six months to leave as well.

“No one has bothered us yet, but everyone is worried,” Hamid said on a recent afternoon, as the smell of newly baked bread filled his eatery.

“We are happy and busy here. If we had to go back, there would be nothing to do and no one to welcome us, only the Taliban and Daesh,” he said, using the Afghan term for the Daesh militants.

For decades, neighbouring Pakistan has provided a safety valve for Afghans who fled successive periods of conflict and repression, hosting up to 5 million at a time. The reception has not always been enthusiastic, but it has been heavily subsidised by the United Nations, and most refugees have easily blended into the large population of ethnic Pashtuns that historically straddled the border.

They have also been a headache for security agencies, who often complained that some refugee camps and communities harboured thieves, drugs and armed militants, and that it was impossible to police a population that flowed loosely across the border and whose members often held no official IDs.

The refugee population has also become hostage to tensions between Pakistan and Afghanistan, with both countries accusing each other of harbouring militants in the porous border regions.

In late 2014, when terrorists invaded a Pakistani military school, killing 141 students and teachers and enraging public opinion, authorities vowed to start sending the refugees back.

Thousands return

The push took many forms, from police harassment to a government publicity campaign, endorsed by officials in Kabul, that urged Afghans to return with the slogan, “My home is my flower.”

After refugee leaders protested, departure deadlines were postponed several times, but the trickle of returnees swelled to tens of thousands early this year, especially after the United Nations added an extra cash bonus for each family once they resettled in Afghanistan.

The surge intensified in June, when Pakistan erected a large gate at Torkham, the major border crossing near Peshawar, and announced that no Afghans could re-enter without a passport and visa. That was tantamount to social death for refugees used to visiting relatives back home and then returning to the safety and prosperity of Pakistan. Riots and shootings broke out at the border gate, but the passport policy stood.

“Torkham gate was the biggest factor. It sent out a very clear message that this was not going to be business as usual,” said Imran Zeb Khan, Pakistan’s chief commissioner for Afghan refugees. He said the cash incentives, as well as public encouragement from Afghan diplomats here, added to the push. By early September, more than 260,000 Afghans had been formally repatriated.

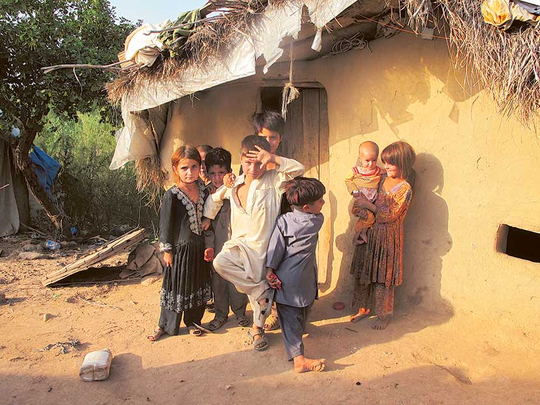

So far, most of the returnees have been undocumented refugees, those who had never registered with UN officials and lived in Pakistan illegally for years. Many were poor families without job skills and little to show for their years abroad; 70 per cent were younger than 24, and 75 per cent had been born in Pakistan. Of an estimated 1 million unregistered refugees, officials said 700,000 still remain here.

Meanwhile, though, longtime refugees such as Mohammed Rauf Derrighel, 63, are fuming.

“I was a child when I came here. Now I am an old man, and suddenly I am being told to go. I feel helpless,” complained the burly, grey-bearded businessman, who was commiserating with a friend at his tailor shop in Islamabad.

— Washington Post