Seoul: Nearly 400 mostly elderly and frail South Koreans began a tearful, emotionally fraught reunion Thursday with family members in North Korea, more than 60 years after they were separated by the Korean War.

After crossing the heavily militarised border into North Korea in a convoy of buses, the families from the South finally met their relatives in a mountain resort that has hosted similar reunions in the past.

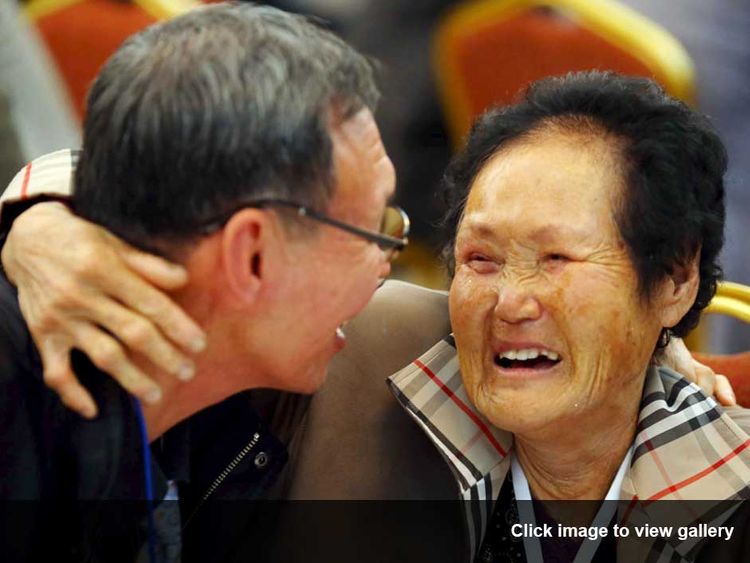

There were moving scenes as divided brothers, sisters, uncles, aunts, step-siblings and in-laws sought each other out and then collapsed into each others’ arms.

For Lee Jeong-Sook, 68, the moment brought her face-to-face with her 88-year-old father, Ri Hong-Jong, who she was separated from when she was just two years old.

Ri was brought into the meeting room in a wheelchair and promptly burst into tears at the sight of his younger sister, Lee’s aunt, who rushed towards him shouting: “Brother!”

“This is your daughter. This is your daughter,” his sister said, pointing to Lee.

Seemingly overcome by the moment, Ri just nodded and squeezed his sister’s hand before asking for news of other family members in the South.

“Almost all died in the war,” she answered.

Millions of people were displaced by the sweep of the 1950-53 Korean conflict, which saw the front line yo-yo from the south of the Korean peninsula to the northern border with China and back again.

The chaos and devastation separated brothers and sisters, parents and children, husbands and wives.

With more than 65,000 South Koreans currently on the waiting list for a reunion spot, those who made it to the Mount Kumgang resort on Tuesday represented a very fortunate minority.

The two ambulances following the South Korean buses on Tuesday testified to the advanced age and, in many cases, poor health, of those making the journey.

More than 20 people required wheelchairs for mobility and one woman needed treatment and oxygen Tuesday morning before boarding her bus. Four others dropped out of the trip altogether, saying they felt too unwell.

The eldest South Korean taking part in the event, 96-year-old Kim Nam-Kyu, was supported by his two daughters as he met his younger sister for the first time in more than six decades.

At first they simply sat in silence, holding hands, and then Kim’s sister produced photos of her family in the North — her son, daughter-in-law and granddaughter.

Details of the meetings came from pool reports provided by travelling South Korean media.

The reunion — only the second in the past five years — was organised as part of an agreement the two Koreas reached in August to ease tensions that had pushed them to the brink of armed conflict.

South Korean Red Cross officials wearing bright yellow jackets had waved the South Korean families off they crossed the border, holding up banners reading “We are people of one nation”.

The reunion programme began in earnest after a historic North-South summit in 2000, but the numbers clamouring for a chance to take part have always far outstripped those actually selected.

Among the generation that actually experienced the division of their families, the vast majority died without ever having any contact with their relatives in the North.

Because the Korean conflict concluded with an armistice rather than a peace treaty, the two Koreas technically remain at war and direct exchanges of letters or telephone calls are prohibited.

After so many years of waiting, the reunions are cruelly short.

Over the next three days, the South Koreans will sit down with their North Korean relatives six times.

Each interaction only lasts two hours, meaning a total of just 12 hours to mitigate the trauma of more than six decades of separation.

In a reflection of the stark economic divide between the two Koreas, all the South Korean families had brought gift packages, including winter clothing, watches, cosmetics and — in most cases — several thousand US dollars in cash.

South Korean officials had warned in advance that a substantial slice of any money handed over would be “appropriated” by the authorities in the North.

After the last reunion, in February 2012, some South Koreans complained that their Northern relatives had felt obliged to deliver lengthy political sermons parroting Pyongyang’s official propaganda.