When eight-year-old Guddi* arrived at the Charbagh Railway Station in Lucknow in the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, she had no one for company except her six-year-old brother Ravi* who gripped her hand tightly. Their parents had died in a road accident and the relatives who were supposed to look after them simply didn’t care. “For several days we had to go to sleep hungry because the relatives we were living with didn’t bother to give us food,’’ sobs Guddi.

Fed up with the ill treatment, she told Ravi they would be better off living on the streets of a city than with their distant family. So one night, a month after arriving, Guddi woke her little brother and together they slipped out of the house and walked to the nearby railway station. She didn’t know where to go or how she and Ravi would survive. “I only knew I wanted to run away from the family that was treating us badly,’’ she says.

Leap of faith

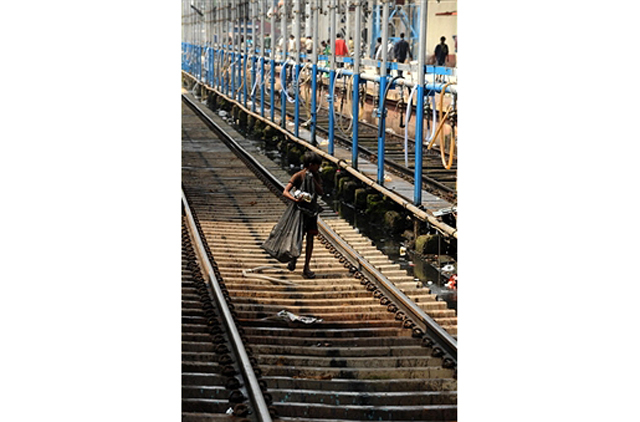

They jumped into a compartment of the first train that stopped at their village railway station and, without tickets, headed into the unknown. “We didn’t know where the train was going or how long it would take to reach a city,’’ says Guddi. But when they arrived at their final destination, Lucknow, they stepped out into the strange city without money, friends, family or a place to go to. In the chaos of a busy station, they could easily have become prey to gangs ready to abuse and exploit them or sinister strangers eager to share drugs with children desperate to escape their grim reality.

Fortunately for Guddi and Ravi, a former runaway, Sanoj – who now works with a UK-based charity, Railway Children – was scanning the station looking for vulnerable children who had recently arrived in the city. The moment Sanoj saw the pair get off the train – clinging to one another, their faces white with tiredness and fear – he knew that they were alone.

Within seconds he approached them and, slowly gaining their trust, told them to relax because they were safe. As someone who once lived on the streets, Sanoj, 22, knows the risks. “I’ve been in their shoes and could easily imagine the danger they were in. If they were not rescued they could end up on the streets and brought into a life of exploitation,’’ he says.

Sanoj was barely ten when he ran away from his home in a village in northern India and arrived at Charbagh Railway Station. He slept on the platform and began refilling water bottles, which he sold to passengers in order to get money for food. Sometimes the station police would beat him and the other railway children because they were a nuisance.

Living in constant fear, there seemed little hope of anything better until a volunteer of Railway Children spotted him and took him to the centre. They gave him a place to live and a basic education. Now he is an outreach team member for Ehsaas – a partner of Railway Children that helps street children and child labourers. He reaches out and is able to connect with children who arrive alone in the station in a way that few others can. He is a figure that children can talk to, look up to and trust.

“Initially Guddi and Ravi were apprehensive to go along with me but after I spoke to them at length, they agreed to accompany me to the charity centre,’’ he says. After getting the duo some food from the railway restaurant he took them to the charity’s office in the city and handed them over to caretakers.

That was a month ago. Today, the two children are being taken care of in the centre. Guddi will be enrolled in school while her little brother will live in a house for destitute children on the same compound. The two will be able to meet regularly and will have a chance to get an education, proper care and a life away from the terror of the streets.

Violence and poverty

Other children are not so lucky. Figures vary widely, but Railway Children says an estimated 120,000 arrive on Indian railway platforms every year. In simple terms, a child arrives alone on a railway platform in India every five minutes.

Violence at home and poverty are two of the main reasons children run away and the most favoured mode of transport they take to escape their village and their past is the train, according to charity workers. Volunteers say the kids are hoping to find a better life and realise their dreams. But far from finding a brave new world, they end up living in terrible conditions, either in the station or on the streets. Constantly under threat from abusers, many resort to drugs and substance abuse for a brief escape.

According to Railway Children, India has the highest number of vulnerable children in the world, and the vast rail network allows children to travel great distances across the country. “We are proud that our work with our partner Ehsaas in Lucknow has created the first ‘child-friendly’ station in India,” says Navin Sellaraju, the charity’s director in India. At Charbagh, officials, police and station vendors are trained to see children as vulnerable and deserving of care.

Since January 2010, station police have handed over about 1,200 unaccompanied children to Ehsaas and several other child-focused local charities. “This pioneering model is being replicated by our partners in Kolkata,’’ says Navin. Railway Children is the brainchild of retired British railway manager David Maidment who was horrified to see a young street girl whipping herself at the Mumbai train station to win sympathy and donations. Desperate to do something, David first worked with Amnesty International reporting child abuse cases.

Determined to do more, David set up Railway Children in 1995. The organisation now works with local partners across India, East Africa and the UK to help children as soon as they arrive in a city station, and help keep them safe from abuse and exploitation. “We fight for vulnerable children who live alone and are at risk on the streets, where they suffer abuse and exploitation,” says Railway Children spokesman Rob Capener. “In the UK, society often denies their existence, and in countries like India the problem is so prevalent that it has become ‘normal’.

“The children run away or are forced to leave homes where they suffer poverty, violence, abuse and neglect. They find themselves on the streets because there is nowhere else to go and no one to turn to. But the problems they face on the streets are often even worse than those they endured at home.”

And timing is key, says Rob. “We race to reach children as soon as they arrive on the streets and intervene before an abuser can. Our work enables us to get to street children before the streets get to them.” The charity works beyond the city of Lucknow. When Raju, now ten, arrived at Sealdah in Kolkata a few years ago, alone and frightened, the charity helped him get on his feet. He was given shelter, food and education. He also became a member of the charity’s support staff, spending hours on platforms spotting vulnerable children and taking them to the charity’s office.

“When I first met Raju, he had just returned from his role as child health volunteer at Sealdah station,” says Wendy Brawn, the international liaison officer at the organisation. “Dressed in his uniform – a white coat with a red cross on the back – he’d spent the morning on the platforms searching for young children arriving alone by train in Kolkata.

“Mistrustful of adults who have let them down in the past, young runaways are able to turn to Raju and other child health volunteers equipped with a first-aid kit to tend to their cuts and bruises,” Wendy says. They then direct them to the shelter. “Peer support such as this can break down barriers of mistrust,” she says. Emboldened by his health volunteer work, Raju now hopes to become a doctor.

Offering timely help to children is vital, says Rob. “Right now, thousands of children on the streets in India are making decisions that can shape their future. Some will be so hungry that they take food from strangers and get lured into a life of slavery. Some will trust a kind-looking woman, only to be forced into a position where they are likely to be exploited and abused.

“The dangers are many, and the adults who will abuse them are all too persuasive. The deciding factor in these children’s lives is early intervention. Getting to the children before the streets do is key to all of our work.” Ehsaas and Railway Children are just two of several charities working to help runaway children across India, and Lucknow is just one station where they work.

In the south of the country, Bangalore is another city that attracts a lot of children simply because it is well known. Other cities that attract a lot of railway children are Mumbai, Kolkata and Delhi. In these cities there are several charitable organisations that place volunteers in railway stations to spot runaway children.

EveryChild, a UK-based charity that has a chapter in India, has helped rescue nearly 300 railway children from Bangalore station and safely reunited them with their families. “EveryChild India helps identify children in desperate situations and provides safe shelters, helps counsel those traumatised by their time on the streets and, where possible, reunites them with their parents or extended family,’’ according to the website.

Changing perceptions

Railway Children not only takes runaway children to safety, but it works with government homes and aims to change perceptions of street children. It also helps children return home to their family if they are willing and able to care for them. Last year 2,088 children were successfully reunited with their families – from a total of 8,641 – and another 2,488 were referred to long-stay homes.

Samir was nine when he left his abusive home, living on the streets but eating at the drop-in centre in Sealdah. Two years later, he started school, and now at 24 he works at the centre that changed his life. Turning his love of art, drama and photography to good use, Samir teaches children to paint, dance and dream of a world far from the squalor and abuse of the streets. He’s just one more bright, caring young man transformed through the work of Railway Children – who aims to help many more escape the dangers of an isolated railway platform.

*names changed to protect identity. Additional reporting by Anand Raj OK