Dubai: Justice delayed is justice denied, there goes the saying.

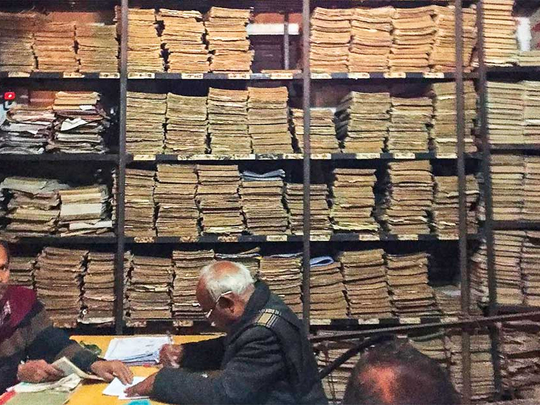

According to a Guardian report in May 2016, as many as 60,000 cases were waiting to be heard at the Supreme Court of India, while at the lower courts, the figure stood at a staggering 22 million.

Decades pass, governments change, witnesses die … but the long winding ways of the judiciary in the world’s second-most populous nation show little or no sign of a change for the better.

While most of these cases involve common people seeking redressals, some such as the 1984 anti-Sikh riots or the 1992 Babri Masjid demolition have profound socio-political concomitants, raising serious questions about the efficacy of jurisprudence in view of the inordinate delays in handing out justice.

From the Bofors scam to fodder scam, from the 1984 anti-Sikh riots to the 2002 Gujarat killings, fortunes of those accused in some of these high-profile cases have vacillated between extremes with new public interest litigations (PIL) filed, new probe committees formed and sometimes with a change in the ruling party at the Centre!

$10m kickback scandal

Take, for instance, the Bofors case — a $10 million kickback scandal over the purchase of artillery guns for Indian Army in 1986, leading to the then prime minister Rajiv Gandhi’s defeat in the 1989 general elections.

In 2004, Delhi High Court quashed all charges of bribery against Rajiv.

The following year, Delhi High Court acquitted the Hinduja brothers — Gopichand, Srichand and Prakash — too, who were alleged to have played a role in the payoffs to secure the gun deal for Bofors AB.

Massive backlog

A study conducted on Delhi High Court by Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy (a not-for-profit company), found that in 91 per cent of cases delayed over two years, adjournments were sought and granted.

As of September 30, 2016, the Supreme Court had nearly 61,000 pending cases.

The high courts had a backlog of more than 4 million cases. And 94 per cent of cases were pending for 5 to 15 years.

All subordinate courts together were yet to dispose off around 28.5 million cases.

At all three levels, courts dispose off fewer cases than are filed.

What could speed up the judiciary:

1. Setting up of more courts.

2. Appointment of competent judges.

3. Less adjournments.

4. Government to have faith in judiciary.

5. Research portal for the legal fraternity.

However, 12 years after those verdicts were pronounced, on September 1, last year, the Supreme Court agreed to hear an appeal, challenging the acquittals!

Three decades on, the hearing continues.

■ Differing views from the legal fraternity

■ Major cases in the judiciary

Another case in point is the 1984 anti-Sikh riots that saw 3,325 Sikhs, according to official estimates, massacred in the aftermath of the then prime minister Indira Gandhi’s assassination by two of her Sikh bodyguards.

34-year-old case

Earlier this month, a Supreme Court Bench headed by the Chief Justice of India, Dipak Misra, issued a two-month time frame to a new Special Investigation Team (SIT) to submit a status report.

This announcement came after a supervisory committee set up by the Supreme Court last August had observed that an SIT constituted in February 2015 had closed many cases without following proper procedure.

Until earlier this month, 11 inquiry commissions have been set up to probe the 1984 anti-Sikh riots, though with little to show for a tangible closure.

Thirty-four years on, the hearing continues.

2G case

But what probably takes the cake is the 2G spectrum case.

In February 2012, Supreme Court ruled that the allocation of 2G spectrum licences to telecom companies was “unconstitutional and arbitrary” and cancelled all the 122 licences that had been granted under a contentious e-auction conducted under the supervision of A. Raja, the then telecom minister.

The apex court’s intervention followed the Comptroller and Auditor General’s office complaining of massive irregularities in the auction, resulting in a $4.9 billion loss to the national exchequer.

Raja and his Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam party colleague Kanimozhi were arrested, along with several others, for their alleged complicity in a scam amount that included so many digits that an ordinary calculator would be ill-equipped to display it in full!

However, surprisingly, on December 21, 2017, the special court in New Delhi acquitted all those accused in the case, citing insufficient evidence and severely castigating the Central Bureau of Investigation for a botched probe.

Inconclusive evidence, fresh PILs, new commissions, retrospective action … the story continues.

And so is the plight of those with the short end of the stick.