New Delhi: Every month, Seema Mishra and her daughter make the trip to a hospital, praying that the blood transfusion the youngster needs to keep her alive will not make her condition still worse.

But Mishra’s fears were realised last month when seven-year-old Aarushi, who was born with a rare blood disorder, was diagnosed with hepatitis C from a contaminated transfusion.

“She has suffered so much already, how come she has to suffer more?” Mishra said as she watched her daughter practise her dance steps.

Experts say blood is not always properly screened and there is a black market supplied mainly by poor Indians who are paid for their blood, especially in rural areas.

Government documents released in June showed that more than 2,000 people said they had contracted HIV from transfusions in the 17 months to March.

The government says some probably falsely blamed transfusions, a more socially acceptable way of contracting HIV than sexual contact.

But blood specialist J.S Arora said infection figures among India’s 150,000 thalassaemia sufferers such as Aarushi, who require transfusions for life, are worrying.

Arora, head of India’s thalassaemia welfare society, estimated up to 40 per cent of sufferers have contracted hepatitis B or C, many more than in other countries. Some have also contracted HIV.

Sufferers cannot produce enough haemoglobin, the substance in red blood cells that transports oxygen, a genetic disorder most common in Asia and the eastern Mediterranean.

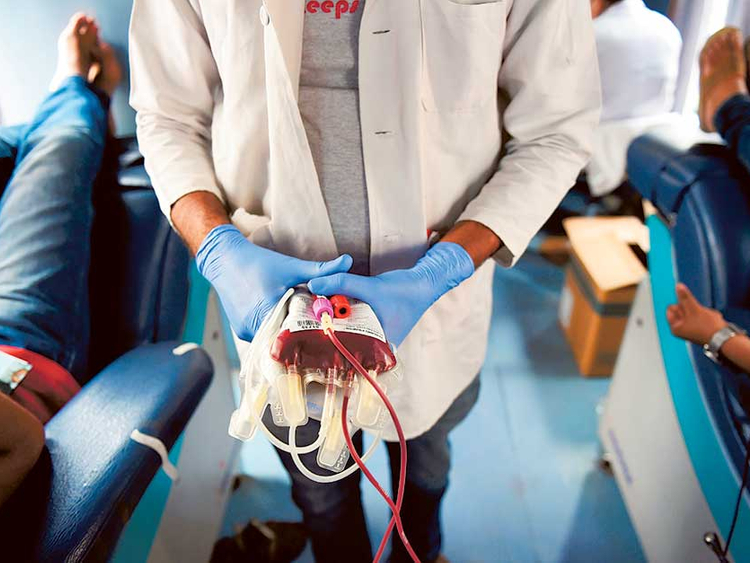

Contaminated blood donations have dropped significantly in recent years thanks to concerted efforts to improve regulation, but experts still hold concerns about the safety and security of supplies.

India has 2,760 licensed blood banks run by government and private hospitals and charities. They must screen for HIV, hepatitis viruses, syphilis and malaria, but the standard of testing varies.

The more sophisticated methods reduce the period when an infected donor does not test positive, but they are expensive and not used everywhere.

Experts say India needs a central collection agency - common in many countries – with rigorous and standardised testing.

“India is a massive country and the range of services is huge, from extremely good to extremely poor,” said Shailaja Tetali, who has studied blood supplies in India’s south.

“There needs to be an overhaul of the system because the way in which blood services are carried out in India is haphazard,” Tetali, from the Indian Institute of Public Health in Hyderabad, told AFP.

In western Gujarat state, families are fighting for a fresh probe into how 32 children, all suffering from thalassaemia, contracted HIV from transfusions in 2011. Eight have since died of Aids, their lawyer Paresh Vaghela told AFP.

Police closed the original case, saying there was no criminal intent, while the hospital allegedly involved says the children received transfusions from more than one place.

The government says thalassaemia sufferers are at higher risk than the general population of contracting an infection because they need so much blood.

“There is no guarantee of a 100 per cent clean blood supply in any country,” deputy director general of blood transfusion services, R.S. Gupta said.

India has long suffered from severe blood shortages, according to the World Health Organisation, which says countries should have blood in reserve from at least one per cent of the population.

Fear of falling ill from donating along with taboos about swapping blood with those of different social castes are blamed for the shortage of volunteer donors.

The shortfall of several million units a year is exacerbated by needless transfusions ordered by doctors which expose patients to unnecessary risk of infection.

As a result patients needing blood at many hospitals have to first provide donors from among friends and family for each unit required.

But experts said some have no choice but to pay people to donate blood - mainly poor Indians desperate for money.

“If relatives don’t want to donate, are not fit to donate or are not there to donate, then how do you get the blood? You pay someone,” the head of one blood bank said.

In her research, Tetali said she found families hiring donors, including an impoverished father who travelled to a city with his daughter suffering leukaemia. He was forced to borrow money to pay touts for a donor so she could receive hospital treatment.

Vinod Bansal, president of the nonprofit Rotary Blood Bank in Delhi, whose donors are all volunteers, said the replacement system bordered on coercion.

Bansal said more properly-screened volunteers are needed to regularly give blood to ensure all Indians, rich and poor, have good access to clean supplies.

Mishra, whose family struggles to pay for Aarushi’s treatment, wants that too, along with better testing technology at government hospitals. “I’m shocked and I’m scared,” she said.