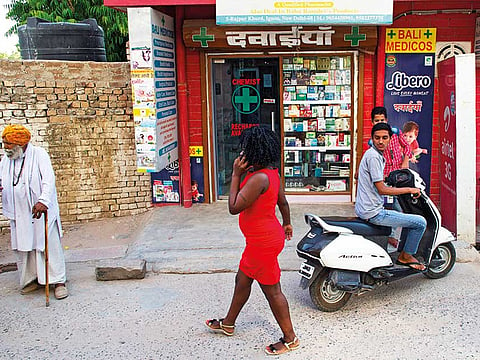

Africans studying in India grapple with racial prejudice

An estimated 25,000 are students at Indian colleges and universities

Greater Noida: Evelyn Benjamin was at home with her 3-year-old son when the manager of her apartment complex and three police officers came to the door.

The middle-age physician who lived upstairs had found what she thought were two hunks of human flesh on the pavement outside and was convinced that Benjamin was responsible.

“She thinks that Africans are cannibals,” said Benjamin, a business-school student from Nigeria.

The meat appeared to be chicken. But the accusation and its racist overtones were nothing new for Africans living in India.

An estimated 25,000 — primarily from middle-class families in Nigeria and Sudan — are students at Indian colleges and universities. They are drawn by affordable tuition and the promise of educational institutions better than those back home, but they often leave feeling insulted and alienated.

False accusations of cannibalism have long surrounded the African community in India. They have grown since an Indian teenager briefly went missing last month in this fast-growing city outside New Delhi — and his mother accused five Nigerian men of eating him.

Unprovoked attacks

Police found no evidence implicating the Nigerians, but after the boy died — reportedly of a drug overdose — packs of Indian men spilled into the streets and for four days attacked black foreigners with fists, sticks and chairs. At least nine victims were hospitalised and one African student group urged its members to stay indoors.

The attacks last month followed a series of violent incidents in 2016: several Africans beaten with bricks and iron rods by a mob outside New Delhi; a Congolese student tied to a pole and whipped for playing loud music; and a Tanzanian woman assaulted and stripped in the high-tech hub of Bengaluru.

African diplomats complained in a statement that the attacks “weren’t sufficiently condemned by Indian authorities” — who continue to insist they were not motivated by racism.

The incidents were a setback to India’s efforts to flex its soft power in Africa. It has courted African medical tourists and in February announced 50,000 scholarships for African students over the next five years.

As a student in southern Nigeria’s Bayelsa state, Benjamin watched Bollywood movies and dreamed of living in India before she enrolled last June at the Jaipuria Institute of Management, a private business school outside New Delhi.

“I was so much in love with India,” she said on a recent evening, moments after the encounter with police. “I thought I would learn the culture, learn to dance. But then I came here and it was a different story.”

Security guards harass Africans visiting her apartment complex and refuse to let their cars into the parking lot, while Indian-driven vehicles are usually waved through, she said. When Benjamin brings her son to the swimming pool, others rush out of the water.

Beyond differences of culture and diet — many Indians don’t eat meat — Africans stand out in a country where light skin is such an obsession that Indian mothers admonish their children from a young age not to go out in the sun and the public spends nearly half a billion dollars a year on “fairness creams” that are routinely advertised on the front pages of national newspapers.

Racist myths about Africans abound. In 2014, a politician in New Delhi led a late-night raid on a house occupied by Nigerian and Ugandan women whom he falsely accused of running a drugs and prostitution ring, ordering one to produce a urine sample in public.

Blessing Odozor, a 23-year-old journalism student from southeastern Nigeria, was outside a KFC in Greater Noida recently when a young Indian man made a lewd gesture and propositioned her.

“It’s gotten to the point that I can’t spend that much time out of the house,” Odozor said. “I only talk to Indians at school.”

Zubair Isa Sulaiman, a 30-year-old from northern Nigeria, said that when children see him walking in the street they sometimes cross to the other side. Others laugh or point. Landlords have refused to rent to him, and shopkeepers overcharge him.

The first Hindi words he learnt were epithets aimed at him: kala (“black”), chor (“thief”), bandar (“monkey”).

“We get a good education here, but the society we find ourselves in is difficult,” Sulaiman said.

His father, a retired accountant, pushed him to study in India after sending his older siblings to China and Malaysia. Nigerian universities are shambolic institutions.

Sulaiman went online to view pictures of Greater Noida and was impressed. Transformed by the explosive growth of New Delhi, 20 miles away, the former farming community has sprouted apartment towers, shopping malls and “knowledge parks” with dozens of private universities.

Yet the residents are still villagers in many ways — the type of people who introduce themselves by their ancient Hindu caste.

“The changes have been fast and furious, and people are barely getting used to having urban people around,” said Vandana Vasudevan, author of a book on Greater Noida called “Urban Villager: Life in an Indian Satellite Town.”

“In that situation, to expect them to embrace Africans so quickly is a bit of a long shot.”

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox