Earth-bound Chinese spacelab to light up sky 'like a meteor show'

Update: 8-tonne Tiangong-1 set to plunge between the afternoon of Sunday and early Monday morning GMT

BEIJING: China's defunct space lab could hurtle back to Earth later than previously forecast, with the European Space Agency saying it may re-enter the atmosphere as late as Monday morning GMT.

The ESA, which is tracking the craft, had earlier given a window of between midday Saturday and early Sunday afternoon GMT.

Chinese authorities have said the roughly eight-tonne Tiangong-1 is unlikely to cause any damage when it comes down and that its fiery disintegration will offer a "splendid" show akin to a meteor shower.

ALSO READ:

The abandoned craft is expected to make its plunge between the afternoon of Sunday and early Monday morning GMT, the ESA said in a blog post announcing its revised forecast.

In its update Saturday the agency said calmer space weather was now expected as a high-speed stream of solar particles did not cause an increase in the density of the upper atmosphere, as previously expected.

Such an increase in density would have pulled the spacecraft down sooner, it said.

The re-entry window remains "highly variable", the ESA cautioned. There is similar uncertainty about where debris from the lab could land.

But there is "no need for people to worry", the China Manned Space Engineering Office (CMSEO) said earlier on its WeChat social media account.

Such falling spacecraft do "not crash into the Earth fiercely like in sci-fi movies, but turn into a splendid (meteor shower) and move across the beautiful starry sky as they race towards the Earth", it said.

Over the past 60 years of space flight, we are nearing the mark of 6,000 uncontrolled reentries of large objects, mostly satellites and upper [rocket] stages.”

Tiangong-1 — or "Heavenly Palace" — was placed in orbit in September 2011 and had been slated for a controlled re-entry, but it ceased functioning in March 2016 and space enthusiasts have been bracing for its fiery return since.

Uncontrolled reentry

The ESA said the lab will make an "uncontrolled re-entry" as ground teams are no longer able to fire its engines or thrusters for orbital adjustments.

A Chinese spaceflight engineer, however, denied earlier this year that it was out of control.

China will step up efforts to coordinate with the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs as the re-entry nears, foreign ministry spokesman Lu Kang told reporters on Friday.

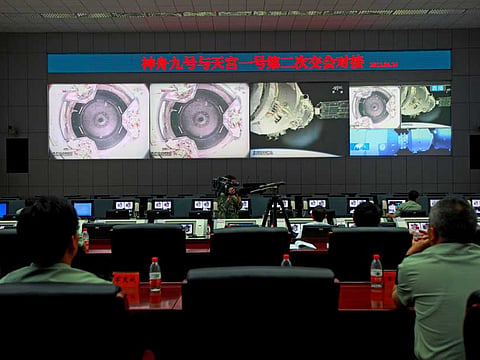

Beijing sees its multi-billion-dollar space programme as a symbol of the country's rise.

It plans to send a manned mission to the moon in the future. China sent another lab, Tiangong-2, into orbit in September 2016 as a stepping stone to its goal of having a crewed space station by 2022.

'Spectacular show'

During the re-entry, atmospheric drag will rip away solar arrays, antennas and other external components at an altitude of around 100 kilometres (60 miles), according to the Chinese space office.

The intensifying heat and friction will cause the main structure to burn or blow up, and it should disintegrate at an altitude of around 80 kilometres, it said.

Most fragments will dissipate in the air and a small amount of debris will fall relatively slowly before landing across hundreds of square kilometres, most likely in the ocean, which covers more than 70 percent of the Earth's surface.

Experts have downplayed any concerns about the Tiangong-1 causing any damage when it hurtles back to Earth, with the ESA noting that nearly 6,000 uncontrolled re-entries of large objects have occurred over the past 60 years without harming anyone.

Jonathan McDowell, an astronomer at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, estimates that Tiangong-1 is the 50th most massive uncontrolled re-entry of an object since 1957, when the Soviet Union launched Sputnik 1 - the world's first artificial satellite.

At an altitude of 60-70 kilometres, debris will begin to turn into "a series of fireballs", which is when people on the ground will "see a spectacular show", he said.

What are the chances of falling debris hitting you?

Over the past 60 years of space flight, nearly 6,000 uncontrolled reentries of large objects were recorded — mostly satellites and upper rocket stages.

More than 90 per cent of those bits of high-tech space junk weighed 100 kilos or more.

“Only one event actually produced a fragment which hit a person, and it did not result in injury.”

Lemmens calculated the odds of being struck by space debris at one in 1.2 trillion — 10 million times less likely than getting hit by lightning.

The China Manned Space programme, which put Tiangong-1 into orbit in September 2011, has been mostly mum on the fate of China’s first space station, designed to test technologies related to docking in orbit.

Daily updates on its official website have tracked its gradual descent — average altitude as of Tuesday was 207.7 kilometres — but not much else.

On Monday, China’s state-run news agency Xinhua cited the agency as saying the spacelab “should be fully burnt as it reenters the Earth’s atmosphere.”

During its operational lifetime, Tiangong took part in two crewed missions, and an unmanned one.

As with all large satellites and spacecraft, the Chinese spacelab had been slated for a “controlled reentry” that would have seen it fall somewhere in the Pacific Ocean, far from human habitation.

In March 2016, however, the space station ceased functioning.

More than 5,000 rockets launched since 1957 have hoisted some 7,500 satellites into orbit, with more than 4,300 of them still in place.

Debris tracker

The US Space Surveillance Network tracks some 23,000 debris objects travelling at speeds of up to 28,000 kilometres per hour.

Statistical models estimate that there are nearly 30,000 objects of at least 10 centimetres across, and 20 times that number measuring between one and 10cm in diameter.

“These form a real collision risk for spacecraft and manned space-flight activity,” said Lemmens.

“What we really fear is the so-called ‘Kessler Syndrome’, whereby objects collide in an exponential cascade, with one collision causing thousands of fragments that in turn start colliding with others.”

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox