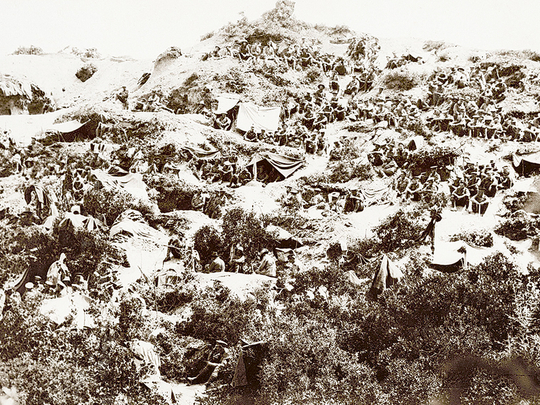

Dubai: A hundred years ago on April 25, 1915, 20,000 Australian and New Zealand soldiers known as Anzacs (Australian and New Zealand Army Corp) landed on a cove in Turkey. It was the First World War and the Anzacs, along with British, British Imperial colonies, including India, and French forces aimed to take the Gallipoli Peninsula and throw the German-allied Ottoman Empire out of the war.

The First World War was Australia’s first international military involvement since becoming a country in 1901, and Australia joined it out of “empire loyalty” to the British, Dr Ben Wellings, a lecturer in politics and international relations at Monash University in Australia, told Gulf News.

It was also a pivotal moment in developing a national identity through values of “mateship,” an Australian expression for friendship, and unity.

The Anzac values have helped Australians find pride in their country’s history that is stained with invasion, occupation and oppression of the country’s indigenous population by the British.

“Since the 1980s, there has been a kind of reworking of what it means to be Australian,” Wellings said.

Australians of all backgrounds are able to identify with the Anzac values, Wellings said, while few choose to identify with the country’s “White Australia” past.

April 25, since 1916, has been known as Anzac Day in both Australia and New Zealand, and is used to remember the sacrifices by the country’s military servicemen and women.

“It has morphed into a commemoration for all sacrifices made by our men and women in wartime including operationally on the home front, people that were prisoners of war [and] people involved in peacekeeping missions. It’s become our most significant day of remembrance,” Pablo Kang, the Australian Ambassador to the UAE and Qatar, told Gulf News.

“Having a celebration like Anzac Day does reinforce the ‘Australianness’ that we share,” he added.

In Australia, the day is marked with dawn services across the country involving processions with the descendants of soldiers, active and retired military personal and the wider Australian public and government.

“It’s become quite symbolic for us,” Rear Admiral Trevor Jones, commander of the Australian forces in the Middle East Region, told Gulf News.

“Anzac Day is about a focus on where all Australian’s can reflect upon all loss of life in the pursuit of a great Australian ideal,” he added.

The importance of the Anzac Day among the Australian public deteriorated in the 1970s when many protested against the country’s involvement in the Vietnam War. But interest picked up in the late 1990s, after the 1993 reburial of the body of an unknown soldier recovered from Adelaide Cemetery near Villers-Bretonneaux in France, Wellings said.

The rising interest of Anzac Day continued into the 2000s, and over the next four years Australia will spend at least A$300 million (Dh857 million) commemorating the century of its involvement in the First World War.

“It’s very strong at the moment. It gets a lot of official support and popular support,” Wellings said.

“It’s very useful for the Australian government diplomatically. They find it very helpful to set the mood with various partners in Europe, Asia and the Middle East,” he added.

Currently, Australia has around 2,200 military personal serving in conflict and disaster areas around the world, with the majority in the Middle East and Afghanistan. Two weeks ago, Australian Prime Minister, Tony Abbott, committed at least 300 soldiers to train the Iraqi Army to fight Daesh.

Wellings wondered if the centenary of the First World War evokes the same emotions of Australia’s military involvement as the questions raised at Australia’s bicentenary in 1988 when thousands protested over issues of national identity and historical interpretation.

Australia also controversially followed the US into invading Iraq in 2004.

Meanwhile, in recent years, the participation of indigenous Australians serving in the military has been garnering attention. At least 1,300 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders served in the Australian military in the First World War even though the then Australian Imperial Force had a policy of soldiers being of “substantial European descent.”

In 2014, “black diggers” were the subject of a play of the same name by Wesley Enoch, an Australian playwright, which highlighted the lives and deaths of the thousand indigenous soldiers who fought for the British Commonwealth in the First World War. Indigenous Australian’s fought for the Commonwealth despite not being recognised as citizens until 1967.

The Australian War Memorial has said Indigenous Australians “were treated as equals … paid the same as other soldiers” in the First World War. But once they returned after the war some found that their family land had been carved up for white veterans. Others who had sent money home came back to find that the protectors of their families had stolen the money and that their families had been broken up and the children taken to orphanages. Most Indigenous veterans were never paid post-war entitlements and denied health-care services available to other veterans.