On Manus Island By the glow of his phone, Benham Satah leads the way into the Manus Island “regional processing centre”, abandoned now by both the Australian and Papua New Guinean governments, and left to ruin and the resourcefulness of those left within.

The massive steel fences that have surrounded this place for years have been, in large part, pulled down, but in haste, and much of the perimeter lies half-dismantled, twisted and torn. Inside is decay and despair, but also defiance.

Two weeks since the camp was shuttered and essential services withdrawn, the 400 men who remain inside are resolute in their determination to stay.

They say they have spent nearly five years living with uncertainty of indefinite detention, and they are adamant there is no possible future - no safety - for them on Manus Island.

But they survive on increasingly meagre resources.

- Kurdish refugee

There is a fraught underground supply chain of food and medicine coming into the camp from Manusians outside anxious to help. But it is ad hoc and vulnerable.

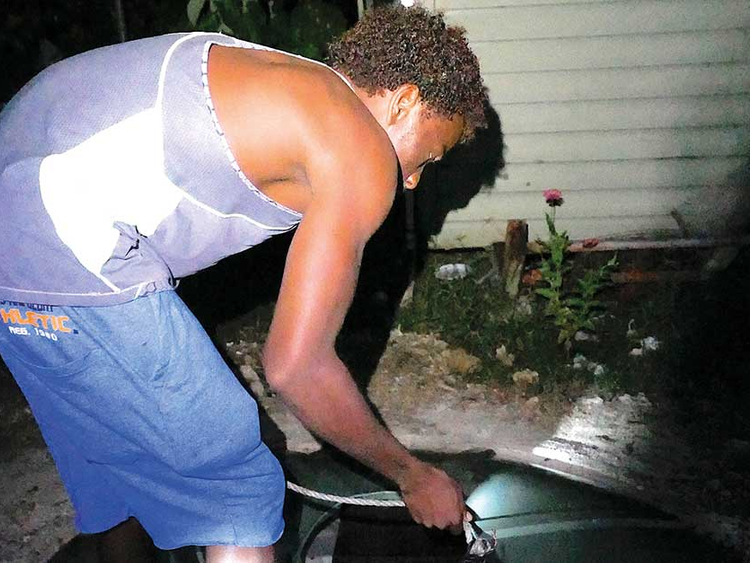

Phones, lifelines to the outside world, are kept charged via batteries dragged from one of the abandoned administrative blocks. Those are kept replenished by solar panels brought from another building.

The camp is rotting in the muggy tropical heat. Refugees have been pulling apart the abandoned buildings, using the timber frames as firewood so that they can cook on earth stoves.

The generators that powered the centre have been removed, and water lines cut. Other items of value and utility - fans, fridges, furniture - have been stolen by people from the surrounding military base or further outside.

The water in the jury-rigged wells the men have been dug has been deliberately spoiled. Rubbish and oil have been poured into them by PNG immigration officers sent in to encourage the men to leave.

Papua New Guinea wants to reclaim the land where until recently it allowed the men - refugees and asylum seekers - to be held on behalf of Australia, which is refusing to resettle them. PNG police have brought officers from across the country to Manus to oversee the final shutdown. Thus far, there has been no force used against the men themselves, but shelters have been torn down, and pumps and pipes sabotaged so they can’t be repaired.

In response, the men who remain in the camp have coalesced into an anarchic collective, co-operating to share the tasks of running the “camp” in the absence of anyone else here, and anywhere else to go.

They say the abandonment has inspired a new unity among them. It is a resilience born of new agency: after four-and-a-half years at the whim of a capricious detention system, the men of Manus finally feel in charge of their lives again.

“All our brothers here are contributing in whatever way they can to make life a little bit easier,” Satah says. “This situation has made us more closer, and more determined. Many of us have experienced war, and this is like a war. We are all together.”

The refugees have established a roster of men “on watch” guarding the perimeter of the camp, for any incursions, and people are assigned jobs based on their skills.

Engineers have supervised the digging of the wells, and what little battery power can be generated is overseen by electricians. Others take charge of dispensing medicines and providing basic medical care.

“Everyone does what they can, what they have the ability to do,” Sudanese refugee Abdul Aziz Muhamat tells the Guardian. “And that way we help each other, because it’s only us.”

The camp sleeps in the day, to avoid Manus’s relentless heat. While the 400 men who remain here are awake at night, there is little movement.

“We are sick,” Satah says. “We are tired and we are hungry.”

“If they come to take us by force, we will not fight back, we cannot, we are for peace. But that is the only way we will go.”

Mostly, the men sit without speaking, in small tight groups, their faces illuminated by the glow of their phones or the light of a fire.

Some, however, prefer the darkness. One man sits in total silence in the very corner of one compound, his forehead resting against the pillar of the decrepit fence. He makes no sound.

In quiet pockets men are bathing, standing up, with water from buckets, others are pulling water from the re-dug wells.

The refugees and asylum seekers who remain inside the Manus “RPC” live largely divided by nationality and language groups, though there appears little hostility to the divisions. In this polyglot refuge, English is the lingua franca.

“Over here is where the Tamils live,” Satah says, nodding to the man standing in the darkened doorway. “The Kurdish area is over here.”

“Here,” he says, reaching the top of a flight of stairs at M Block. “This is where my roommate Reza Barati was murdered. “

In February 2014, in the midst of a riotous invasion of the centre from outside, Satah watched from the doorway as Barati was struck twice in the head with a stick spiked with nails, before a succession of guards kicked the prone Iranian and, finally, a rock was dropped on his head, the injury that ultimately killed him.

While Barati was reportedly attacked by up to 15 people, including expatriate guards, only two local men were ever charged, convicted and sentenced - to five years’ jail. Eight months ago, one of those escaped from prison and hasn’t been apprehended since.

On a wall in the middle of the centre are posted pictures of men who have died in the detention centre - Barati, murdered; Faysal Ishak Ahmed, who collapsed after being rebuffed from medical help after dozens of fits ; Hamid Kehazaei , who died of sepsis after a small infection in his leg overtook his whole body; Hamed Shamshiripour , who killed himself after more than a year of warnings to Australian authorities he was psychotic and a danger to himself and others.

Over tea - there is a little sugar remaining - Satah is mournful for lost friends, but is moved to rage as he says hope for the future is what has been damaged most.

Most of the refugees have abandoned any ideal of Australia as a country that might one day welcome them.

“I don’t care about Australia, I don’t care where they send me, I just need to be somewhere safe,” a Kurdish refugee, who declines to give his name, says. “Safety is all I want, and we are not safe here.”

Far beyond the issue of their alternative accommodation on Manus not being ready (power and water is intermittent in the places refugees are being encouraged to relocate to), safety is the major reason why men are still in this place.

There are rising tensions in Manus between the local population and the transplanted refugee one. The province’s only city, Lorengau, is small, monocultural and close-knit. It is a conservative place and almost everybody is linked by the familial bonds of wantok that criss-cross all over the island. The imposition of several hundred young men from vastly different backgrounds into their town, living on their land, has had the obvious outcome from Manusians. Tensions are especially high over relationships between refugee men and local women.

After dark, many refugees say, they are too scared go out, and almost all have a story about being attacked and robbed. Some show scars from having been assaulted by gangs wielding iron bars and machetes.

There are other men still in the detention centre who have never left it after being sent there more than four years ago.

But at the same time, there are many Manusians who are supportive of the refugees and empathetic to their situations. Many Manusians are trying to assist the refugees stranded inside the detention centre.

Ezatullah Kakar still has the kickboxer’s physique that made him a champion in Pakistan, but he says his mind has been weakened by years of indefinite detention, and the capricious, shape-shifting regime which has held him.

“I lost my memory in this place. I can’t remember my past and I can’t think about my future. The future for us is the next day; will we survive?”

Hassan, who is older, gives his first name and his six-digit boat ID, PRT094, by way of introduction.

“I am like everybody else. Waiting for my life back. Waiting for ... I don’t know what.”

He has two children, now aged 11 and 15, he hasn’t seen in four-and-a-half years.

“I miss them every day. All those years I have lost.”

Hassan sleeps on top of a shipping container, surrounded by a makeshift clothesline bearing all the clothes he owns.

Each night he climbs a ladder to reach his makeshift bed. It is cooler outside, he says, and safer up high.

“When they come,” he says of the police raid he expects, “I can kick the ladder away and I am more safe. But only a little.

“Goodnight.”

In the morning, Satah is calmer. He says he slept little. He takes a dangerous number of sleeping tablets each night, but his tolerance is so high, after years uninterrupted consumption, they barely have any effect.

“My mind is too hard to control. It is hard to think properly, because there is so much pressure on us. Four-and-a-half years is too long. Still, we don’t know what will happen to us.

“So we just wait. And we try to survive.”