BANGKOK

The insurgent group announced its existence with a predawn attack on three Myanmar border guard posts. Hundreds of Rohingya militants, armed mainly with knives and slingshots, killed nine police officers and seized weapons and ammunition.

It was about time, Naing Lin, 28, said of the October attack near his village, Kyee Kan Pyin.

“The government is torturing us,” he said by phone this week. “The aim of the group is to protect our rights. That’s all. They are doing what they should do.”

The beginning of an armed resistance is just one of several developments that are shifting the landscape for the Rohingya, Myanmar’s persecuted Muslim minority, with potentially far-reaching consequences.

The group that attacked the border posts, Harakah Al Yaqin, is believed to have several hundred recruits, substantial popular support and ties to Saudi Arabia and Pakistan, according to a report by the International Crisis Group. Separately, there has been a surge of international humanitarian and political support for the Rohingya cause, mainly from Muslim countries that have cast the Rohingya as the Palestinians of Southeast Asia.

The combination threatens to internationalise and escalate a long-simmering conflict. The Myanmar government has responded to the attacks with a sweeping counter-insurgency campaign that witnesses and human rights groups say has included the killing of hundreds of civilians, the burning of villages and the systematic rape of women and girls.

In addition, some analysts fear that turning the Rohingya into a transnational Muslim cause could draw foreign militants of varying stripes to Myanmar, adding terrorism to an already combustible mix and giving the Myanmar military a convenient excuse for a draconian response.

But after decades of persecution and violence, to which the rest of the world largely responded with a shrug, some Rohingya say an armed response is overdue.

“They are doing good things,” Naing Lin said of the insurgents. “They are protecting our rights. If it’s needed, I might join them.”

The attack on the border posts in Rakhine state was a “game changer,” according to the International Crisis Group’s report.

Harakah Al Yaqin, Arabic for “Faith Movement,” is directed by about 20 Rohingya emigres in Saudi Arabia and led on the field by another 20 or so Rohingya with international training and experience in guerrilla warfare, the report said. It is well connected in Pakistan and Bangladesh and appears to be attracting financial backing from the Rohingya diaspora, the report said.

The militia enjoys growing support from many Rohingya in Myanmar who see it as the only alternative to government repression, the International Crisis Group said. The organisation warned that a continued heavy-handed approach by the military would backfire, attracting stronger backing from the Rohingya and possibly inspiring foreign groups to join the conflict.

There have already been signs of interest by Daesh. In November, Indonesian authorities arrested three men who claimed allegiance to the Daesh and were accused of planning to bomb prominent sites across Jakarta, including the Myanmar embassy.

This month, Malaysian authorities detained a man who the government said was a Daesh follower heading to Myanmar to carry out attacks.

“All this clearly demonstrates Daesh slowly and steadily making inroads to influence the Rohingya issue,” said Rohan Gunaratna, a professor of security studies at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore. “You can even say it’s an attempt to hijack the Rohingya agenda.”

The Myanmar government has largely denied allegations of human rights abuses, and it says it is responding to the situation according to the rule of law.

The government has barred journalists and aid workers from entering the conflict area, in northern Rakhine state just over the NAF River from Bangladesh, and accusations that the military is carrying out a campaign of murder, rape and arson have not been independently verified.

But the reports and images of violence there have fuelled the concern of other countries in the region, especially Bangladesh and Malaysia.

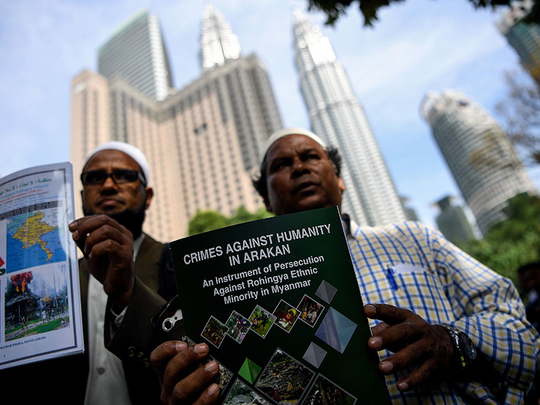

On Thursday, the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, a coalition of 56 countries, held an emergency session in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, where it called for an immediate halt to military operations in Rakhine state, an independent investigation into accusations of human rights abuses, and humanitarian aid to the affected areas.

At the same time, countries in the region are wary of escalating violence in their backyards.

Bangladesh, struggling to contain the spread of extremist networks within its own borders, is concerned about the rise of an insurgency next door and the prospect of Rohingya militants using Bangladesh as a base to carry out attacks in Myanmar.

Refugees fleeing the crackdown in Myanmar have been “pouring over the border” into makeshift settlements, said Shafqat Munir, a research fellow at the Bangladesh Institute of Peace and Security Studies. “If there is a risk of potentially radicalised people coming in, that presents quite a challenge.”

Still, in contrast to previous crises, there has been little effort to stem the flow by sending refugees back to Myanmar. About 65,000 Rohingya are believed to have arrived in Bangladesh since October, joining about a half-million already living in the refugee camps near Cox’s Bazar.

Islamist organisations, including the powerful Hefazat-e-Islam, organised large rallies in Dhaka, the Bangladeshi capital, in November and December, urging the government to give the Rohingya shelter.

Madrasa students have journeyed to the refugee camps from far-flung cities to help build temporary shelters. Others travel halfway across the country from Dhaka and beyond to hand small gifts of cash to the once-reviled Rohingya.