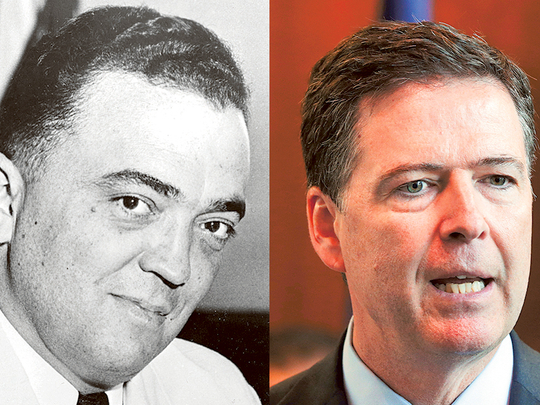

Washington: In July, after FBI Director James B. Comey declined to bring charges against Hillary Clinton for her handling of classified emails, leading Democrats hailed his leadership.

“This is a great man,” said Nancy Pelosi, the House minority leader. “We are very privileged in our country to have him be the director of the FBI.” No one, added Harry Reid, the Senate minority leader, “can question the integrity” of Comey.

But on Friday, after Comey revealed that the FBI would review newly discovered emails potentially related to the case, Democrats changed their tune.

Reid all but accused him of criminality, writing to Comey, “You may have broken the law.”

Comey, who was once so broadly admired that the Senate confirmed his appointment in 2013 by a vote of 93-1, has emerged as the most vivid example of how difficult it is for institutions to remain insulated from partisan combat in this hyperpolarized era.

Clinton and her opponent, Donald Trump, who has made incendiary statements against Comey, are practicing the politics of total war, where there can be no non-combatants or neutral actors. Supporters have to be rallied, and adversaries must be distinguished from allies.

“Everything now gets weaponised,” said David Axelrod, a former adviser to President Barack Obama. In their response to Comey, he said, “the Clinton people saw a strong rebuttal against him as a way of galvanising their own forces.”

That Clinton would make the FBI director a target of her campaign’s wrath is deeply troubling to some Republicans, including those who are no admirers of Trump and believe that she is compounding what they see as the Republican candidate’s irresponsible behaviour.

Even more worrisome, they say, is that the attacks are eroding what little faith the public still has in government.

“What we’re seeing in this election, with Trump saying the election and everything else is rigged and now this attack by Hillary and her people on the FBI, is basically an attack on our form of a constitutional government,” said former Sen. Judd Gregg, R-N.H. “They’re undermining the core elements of what gives our government credibility.”

Axelrod said Hillary Clinton had a “legitimate” criticism of Comey, and her advisers felt they had no choice but to exert pressure on the FBI director to reframe a potentially damaging narrative. In the minds of Clinton’s aides, Comey made himself fair game when he issued a vague three-paragraph letter and inserted himself and his agency into the final days of a high-stakes contest.

“By taking this highly unusual, unprecedented action this close to the election, he put himself in the middle of the campaign,” said Jennifer Palmieri, Clinton’s communications director. The campaign’s advisers also felt they had to act, she added, because they believed that Trump would distort the letter.

Yet the evolution of Democrats’ handling of Comey’s letter illustrates just how tempting, and rewarding, total-war politics can be.

When Clinton first addressed the inquiry on Friday evening, hours after news of Comey’s letter emerged, she was firm but also careful to avoid anything that could be seen as a personal criticism of the director. “It’s imperative that the bureau explain this issue and question, whatever it is, without any delay,” she told reporters in Iowa.

On Saturday, though, Clinton saw an opportunity. When she referred to “the FBI director,” the Democratic audience responded with a chorus of boos for an official who was appointed by Obama.

“It’s pretty strange to put something like that out with such little information right before an election,” Clinton told supporters in Daytona Beach, Florida, winning applause. “In fact, it’s not just strange; it’s unprecedented, and it is deeply troubling.”

Similar emails to donors targeting Comey were soon sent.

And by Sunday, Clinton’s top surrogates felt comfortable going even further, seeing that their supporters were roused by the eleventh-hour story. Sen. Tim Kaine of Virginia, Clinton’s running mate, said at a campaign stop in Michigan, “It has kind of revved up some enthusiasm — a little bit of righteous indignation and righteous anger.”

John D. Podesta, her campaign chairman, when asked on CNN about how WikiLeaks had obtained his hacked emails, used the opportunity to ridicule the FBI director.

“Maybe Jim Comey, if he thinks it’s important, will come out and let us know in the next nine days,” Podesta said.

Later that day, Reid all but accused Comey of violating the Hatch Act, which bars government officials from engaging in any activity that can influence elections.

“Through your partisan actions, you may have broken the law,” Reid, D-Nev., wrote in a letter to Comey.

What started as a request for additional information had escalated into claims of criminality in less than 48 hours.

Such accusations are unfamiliar territory for Comey, a Republican. The political left and Centre hailed him when, as deputy attorney general to President George W. Bush, he staged a made-for-Hollywood intervention at the hospital bed of Attorney General John Ashcroft to prevent other administration officials from making Ashcroft approve aspects of the National Security Agency’s domestic surveillance program.

And Comey was, of course, respected enough across party lines to be tapped by Obama.

“I’ve found him to be a straight guy,” Vice President Joe Biden said Friday shortly after the letter was disclosed.

Comey remained silent over the weekend, perhaps not wanting to add accelerant to the raging political fires. But by doing so, and by not disclosing further information about what new material his agents may have discovered, he has only fuelled speculation.

“It is a shame how contentious everything now is, this state of our public discourse,” said Donald B. Ayer, a deputy attorney general under President George Bush. “But he broke the most fundamental rule as a prosecutor: You either put up or shut up.”