COLUMBIA, South Carolina: They pooled by the thousands in the scorching July heat - white and black, old and young, civil rights veterans and everyday Southerners who grew up with the symbols and assumptions of the racial order of the South. They waited quietly at first, but eventually erupted into spontaneous chants of “Take it down!”

And when the red and blue Confederate battle flag was finally, permanently lowered here from its place of honour on the grounds of the South Carolina State House, they chanted again: “USA! USA!”

The banishment of perhaps the most conspicuous and polarising symbol of the Old South from the seat of South Carolina government Friday morning was the culmination of decades of racially charged political skirmishes.

At issue were vexing questions about how a state that was first to secede from the Union - and then later raised the battle flag in 1962 when white Southerners were resisting calls for integration - should honour its Confederate past.

It was a conversation that seemed like it might never end here, until it was hurried to a resolution by unspeakable horror: the massacre of nine black churchgoers in downtown Charleston last month, and a gathering sense of outrage and offense that was felt even by many white conservatives who had previously supported the flag. The arrest of the alleged gunman, 21-year-old Dylann Roof, who posed proudly with the flag and apparently posted a long racist manifesto online before the massacre, was the flag’s final undoing.

“It’s a long time coming,” said Edward Dunn, 47, an African-American who works as a grocery clerk, who had come with his wife and two children to see the flag come down. “It just shows that South Carolina is trying to do something to unify the races.”

There were some who watched with heavy hearts. Joy Jackson, 76, walked to the State House with a battle flag wrapped around her shoulders like a shawl, and with a timeworn photo of her grandfather, William Marcus Faircloth. She said he had fought for the Confederacy and was wounded three times in battles in Virginia. The flag, she said, was to honor veterans like him.

“I hope you don’t hate me,” she said to a black journalist who was wrapping up a video interview with her.

Others saw the deaths at Charleston’s Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church as part of an ugly continuum that the flag represented, and the decision to lower it as an extraordinary shift in thinking.

“This right here is an acknowledgment that, yes, this was put up in defiance,” Kelvin Peoples, 41, said. “Yes, this flag is used by persons who are inclined to racial superiority thoughts, and it’s offensive to a lot of people.”

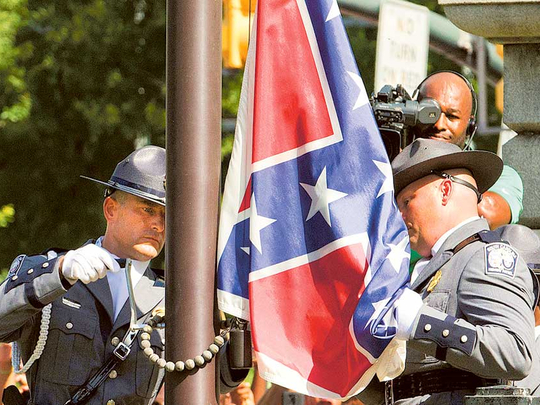

Around 9:45am, a seven-member gray-suited honour guard from the South Carolina Highway Patrol appeared in front of the State House, where state officials estimated that more than 8,000 had gathered.

About 20 minutes later, Gov. Nikki R. Haley, who had asked the state Legislature to change the law to allow the flag to be removed, walked onto the steps of the State House, joined by her husband, Michael; the Rev. Norvel Goff, the interim pastor of Emanuel AME Church; Mayor Joseph P. Riley Jr. of Charleston; and two former South Carolina governors, David Beasley and Jim Hodges.

Within minutes, the troopers - five white and two black - began a slow, closely orchestrated march toward the 30-foot pole. There had been questions here about how the flag would come down; before Friday there had been no visible way to lower it, and on June 27, a protester managed to pull the flag down briefly, but only by shimmying to the top of the pole using climbing gear. It turned out there was an internal mechanism that could raise and lower the flag.

Two of the white-gloved troopers crossed the decorative fence that has long stood around the pole. Soon one of them was turning a crank inserted into the pole and the flag began to descend. The crowd cheered. It took less than 30 seconds for the flag to come down. It will now be housed at the Confederate Relic Room and Military Museum, a state-supported museum near the State House.

By late afternoon the flagpole was removed, too.

Jack Bass, an emeritus professor of social sciences and humanities at the College of Charleston, called the flag lowering “a high moment for South Carolina” that could have some practical effect. Haley and other state officials have worked hard to lure multinational corporations and fuel job growth in recent years, and Bass said the state could have an easier time with that task now.

But Bass and others said it was far from clear if this rare liberal victory in a state thoroughly dominated by conservative Republicans would result in other more substantive policy changes, like an expansion of Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act. Haley, a Republican and staunch fiscal conservative, has opposed the idea.

In the crowd, Hesh Epstein, 53, rabbi at Chabad of South Carolina, said the lowering of the flag was “a sign of progress, of sensitivity to people who for a very long period of time felt they didn’t have a voice.”

“In Judaism, symbols are always meant to move us to real actions, to be better people,” he said. “If this moves us to be more generous and kind and righteous, then we have something of value we’ve really accomplished.”

— New York Times News Service