SILVER SPRING: Many people can turn on the lights and then they’re not helping the Earth,” said Tuvey Le, a student at William Tyler Page Elementary School in Silver Spring, Maryland. “So it’s better to turn off more.”

Le has been passionate about helping the Earth — she pauses, mulling — since she was 7 or 8 and joined her school’s green team as an environmental ambassador in classrooms and at home. Learning about the environment at school sparked her passion.

“I use less water when I’m brushing my teeth and then my lights are off when I’m changing, so I can save electricity,” she said. “At the end of the day, I always turn off my iPad before I go to bed,” and she’s sparing with shower water.

The state’s push for green schools was highlighted in a recent Chesapeake Bay Program report, which said that in 2015, more than 80 per cent of the certified sustainable schools in the improving watershed were in Maryland.

Beyond ‘sitting, listening’

The Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement was signed in 2014, and Maryland’s Republican Gov. Larry Hogan established Project Green Classrooms in June, signing an executive order that renewed the state’s commitment to expose students to the outdoors and environmental issues.

As a result, students are not just “sitting and listening” to teachers anymore, but taking an active role in their classes, said Britt Slattery, director of the Center for Conservation Education and Stewardship with the Maryland Department of Natural Resources.

“They have a remarkable ability to comprehend these vigorous concepts when they’re actively engaged in their learning,” said Slattery, who is also a co-coordinator of Project Green Classrooms.

“They’re able to see that they have a powerful role in shaping the future of their world, so they are much more interested in the learning.”

School programmes in the watershed that adopt sustainable practices and teach students to be environmentally literate are helping to save the bay now, and ensuring it remains well, said Tom Ackerman, vice president of education with the Chesapeake Bay Foundation. Education, he said, is the “best, really long-term, solution for protecting the health of our environment.”

Millions in the programme

Students at Page are a portion of the roughly 2.7 million students in the Chesapeake Bay watershed, and other states, including Virginia, and the District of Columbia also have taken steps to certify green schools and incorporate environmental literacy into curriculums, Ackerman said.

Data from about 120 schools in the Maryland Green Schools programme show sustainability efforts conserved more than 700,000 gallons of water and a drop of nearly 7 million kilowatt-hours from 2015 to 2017. “It’s preparing kids for the 21st century economy and the 21st century citizenry,” said Ackerman.

Students have also developed an understanding of the impact of their personal actions, leading them to eco-friendly habits, said Michele Dean, the school’s green team leader and a prekindergarten teacher.

Recycling, a way of life

As lunch wraps up, a steady stream of students bring their trays to the centre of the cafeteria where different coloured receptacles are located. Without hesitation, they methodically separate food remnants, cardboard trays and plastic containers. Leftover water is poured into buckets to be repurposed.

“Very rarely do we have to remind them,” said Dean, who has led the green team at Page for more than 10 years. “They just know that we have to recycle at lunch.”

Before the school installed hand dryers, they knew to use one — just one — paper towel. “It’s a natural thing here,” she said.

Sophie Hofherr, a first-grader and green team member, said she recycles every day. If people don’t take care of the environment, the consequences would be dire, the 6-year-old said.

“If you litter and you don’t recycle ... the Earth will get all dirty and then if people stop taking trash and putting it away,” said Sophie, “the Earth will just fall apart and it will be all garbage.”

You have 15 minutes - to think of a solution

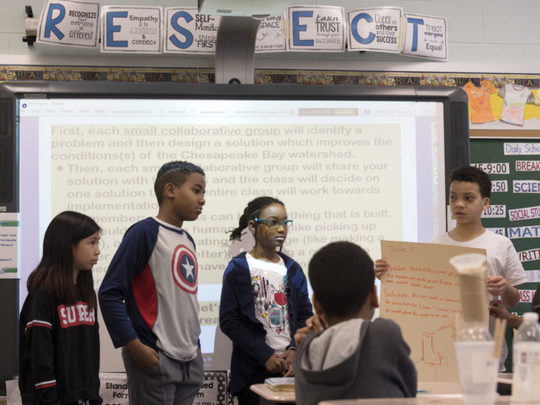

The activity and noise in one of Carlette Jameson’s morning science classes at Page rival a sporting event’s. Jameson’s voice pierces the din, “you have less than a minute.”

Visible panic flits across the faces of fourth-graders clustered in groups around the classroom, their construction paper rustling. Armed with coloured markers, they frantically finish an assignment that would challenge many college-educated adults: identify and offer a solution to environmental problems in the Chesapeake Bay. In 15 minutes.

Sophia Carey, a student, said her group wanted to decrease the amount of snow salt and chemicals used because they cause water pollution.

Their solution was an underwater vacuum to suck up toxic water and clean it that seemed flawless. But then Jameson asked what they would do with the residual chemicals.

It would go to a landfill, somebody suggested.

“So then that goes to another type of pollution. What is that?” Jameson asked.

“Air pollution,” the students said as a chorus.

As the period drew to a close, no group had come up with a solid solution, and the room once again filled with overlapping voices engaged in spirited debate.

“This is a working thing,” Jameson told her class. “The goal is to get students to think critically, Jameson said.

“I didn’t really know what things could pollute water and air, but then I learned more things than I thought could do it,” said Sophia.