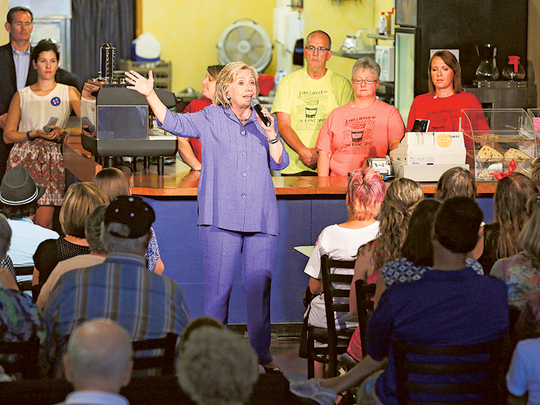

Portsmouth: Hillary Rodham Clinton hit on a variety of subjects at her sun-splashed campaign rally here this weekend, but not once in her 30 minutes of speaking did she utter these words: Bernie Sanders.

Campaigning 1,200 miles away in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, Sanders was interrupted for applause 77 times — but not a single line in the senator’s nearly hour-long stump speech referred to Clinton or any other Democratic primary opponent.

The Republican presidential campaign is being dictated by how the 17 candidates, led by Donald Trump, attack each other — from policy disagreements to nasty personal barbs.

The Democratic race stands in stark contrast. Despite tightening polls, the two leading candidates refuse to draw sharp contrasts, let alone criticise each other, leaving voters to discern the differences in their agendas and priorities largely on their own.

Former President Ronald Reagan famously pronounced an 11th commandment for the GOP: “Thou shalt not speak ill of any fellow Republican.” In the 2016 contest, however, it’s the Democrats who are heeding Reagan’s call — at least so far.

Sanders boasts that he never has run an attack ad in his four-decade-old career in politics and, in an interview on Saturday in Iowa, explained his rationale for not going after his chief rival this time.

“You’re looking at a candidate who honestly believes that the discussion of the serious issues facing the American people is not only the right thing to do, it’s good politics,” Sanders said. “I know the media would like me to attack Hillary Clinton and say all kinds of terrible things and tell the world that I’m the greatest candidate in the history of the world and everybody else running against me is a jerk and terrible, awful people. Nobody believes that stuff.”

Sanders and his campaign strategists have calculated that to beat Clinton he must expand the electorate — and that going negative will turn off too many potentially new voters.

“We have to follow the formula that brings people into the process,” said Sanders adviser Tad Devine. “Otherwise we can’t win.” When pressed by reporters, however, Sanders is willing to explain his policy differences with Clinton.

Recent polls show Sanders gaining on or jumping ahead of Clinton — a surge he attributes to his progressive economic and social agenda and his populist pitch to take on “the billionaire class.”

In New Hampshire, home to the nation’s first primary, an NBC/Marist poll released on Sunday shows Sanders leading with 41 per cent of Democratic voters, followed by Clinton at 32 per cent. The same poll in July had Clinton ahead, 42 per cent to 32 per cent.

In Iowa, which holds the first caucuses, the NBC/Marist survey showed Clinton leading Sanders 38 per cent to 27 per cent. Her advantage there has narrowed since July, from 24 percentage points to 11. A week ago, a Des Moines Register-Bloomberg Politics poll showed the Iowa race even closer, with Clinton ahead 37 per cent to 30 per cent.

There are some signs that the intensifying race may lead to more direct engagement between the two candidates. The first primary debate, scheduled for October 13, is certain to showcase their differences.

Looking ahead to the debate, Clinton’s campaign chairman, John Podesta, told reporters last week, “The ideas that she’s put out, we feel very confident, contrast with the ideas of the other Democrats, including Sen. Sanders.”

When asked to specify the areas in which Clinton believes she differs from Sanders, Podesta demurred. But he highlighted several key policy proposals, including plans to combat drug and alcohol addiction, reduce student loan debt and prioritise family-friendly issues such as equal pay and early childhood education.

Clinton assiduously has avoided referencing Sanders, in part because she cannot afford to alienate his impassioned supporters; should she win the Democratic nomination, she will need their votes and enthusiasm in the general election.

To that end, Clinton has passed on even the easiest contrasts. She indisputably has more foreign policy experience than Sanders, yet gives her tenure as secretary of state nary a mention on the stump.

At the Portsmouth rally, Clinton said, “Other candidates may be out there hurling insults at everyone, talking about what’s wrong with America and who’s to blame for it, but I’m going to keep doing that I’ve always done: fight for you and fight for your families.”

Some voters in the crowd said they wished Clinton would explain the differences between her and Sanders. “That’s exactly what we want to hear as voters,” said Beth Chambers, 46. “What do you think of your opponent? Why should we vote for you over him?”

In a rare sit-down interview Friday, Clinton took what was widely interpreted as a veiled jab at Sanders. “You can wave your arms and give a speech, but at the end of the day are you connecting with and really hearing what people are either saying to you or wishing that you would say to them?” she told Andrea Mitchell of NBC News.

The next day, however, Clinton insisted to reporters that the comment was not about Sanders. “I was talking about Donald Trump,” she said, referring to the brash GOP front-runner. “It certainly is clear that my campaign is focused on the Republicans.”

Sen. Jeanne Shaheen, D-N.H., hit on the same theme as she formally endorsed Clinton in Portsmouth on Saturday. She decried the Republican primary as a “round-the-clock spectacle of scapegoating and name-calling” but said Clinton “always chooses to lift people up rather than tear people down.”

There is little doubt, however, that Clinton will try to tear Sanders down if and when she decides she needs to. In 2008, she was stinging in her attacks on Barack Obama, including her infamous “3am phone call” ad, which suggested that she, not Obama, had the national security experience and diplomatic relationships to be commander in chief.

Some of Clinton’s campaign surrogates have started doing her dirty work for her. Sen. Claire McCaskill, D-Mo. said Sanders, an independent from Vermont and self-described democratic socialist, is too liberal to get elected. Connecticut Gov. Dan Malloy (D) said Sanders’s record on guns was “anathema” to many Democrats. And Rep. Joaquin Castro, D-Texas, criticised his outreach to Latinos.

Asked about those volleys on Saturday, Sanders told reporters: “Don’t tell anybody: I think they’re getting nervous.”

Former Maryland Gov. Martin O’Malley, who is trailing far behind Clinton and Sanders in the polls, has been more aggressive in directly criticising them. He regularly calls himself a “lifelong Democrat,” in contrast with the independent Sanders. And he has referred to the State Department email controversy dogging Clinton.

“What is our message in the Democratic Party?” he asked at a recent house party in Hollis, N.H. “It seems our brand is, what did Hillary Clinton know about her e-mails and when did she know it, and did she wipe her server or did she not?”

Jim Manley, a Democratic strategist supporting Clinton, said he sees no upside for her in attacking Sanders. “That kind of contrast is just the kind of oxygen his campaign needs and it would feed his fund-raising,” he said.

As for Sanders, Manley said going negative on an opponent “is not who he is. Doing so would seem forced and inauthentic. He’s always been about fighting issues — big issues. Personal attacks are not his forte.”

Yet even by talking about the issues, Sanders frames a contrast with Clinton. As he rallied about 2,000 people on Friday night in Cedar Rapids, he said he was putting the nation’s ultra-wealthy — the kind of people who piled into manses from Nantucket, Mass., to Aspen, Colo., this summer to hear Clinton speak at fund-raisers — on notice that “their day has come and gone.”

Without mentioning Clinton, Sanders regularly highlights policy areas where they differ. He wants to reinstitute Glass-Steagall, a Depression-era banking regulation; she has not taken a position. He opposes the Keystone XL oil pipeline; she has no position. He voted against authorising the Iraq war; she voted for it, though now says her vote was a mistake.

At the Cedar Rapids rally, neighbours Valerie Smith and Victoria Kircher, both 53, said they appreciated that Sanders did not talk about Clinton.

“Just tell us who you are,” said Smith, adding that she cannot stand it when Trump calls his rivals “stupid” or “low-energy.”

“Act like grown-ups,” Kircher said. “I hate bashing.”