TENOSIQUE, Mexico

Unable to find work and terrified by the street gangs that brazenly roamed the streets, Karen Zaldivar was one of tens of thousands of young people who fled Honduras in 2014.

Caught trying to slip across the US-Mexico border, she was promptly deported.

Last year, Zaldivar set out again, but with a new destination: Mexico. She now lives in a small city just north of the Guatemalan border, along with growing numbers of other Central Americans who have concluded that if they can’t reach the United States, the next best thing is Mexico.

“I decided to make a life here,” she said at a small open-air restaurant in Tenosique, where she works in the kitchen, frying fish. “It’s calmer and safer.”

Estimates of how many Central Americans are living in Mexico are hard to come by, in part because some, such as Zaldivar, have obtained forged Mexican identity documents. But statistics show an increasing number are staying legally by seeking political asylum or humanitarian visas.

Asylum applications in Mexico nearly tripled over three years, reaching 3,424 in 2015. Asylum requests this year are poised to be twice that, human rights advocates say, with most filed by Hondurans and Salvadorans.

The number of migrants seeking to stay in Mexico pales in comparison with the droves heading to the US — more than 400,000 people were apprehended at the US Southern border in the fiscal year that ended in September, most of them from Central America.

But the burden on Mexico and other countries is likely to increase if President-elect Donald Trump makes good on his promises to beef up border security and deport up to three million people living in the US illegally.

Jaime Rivas Castillo, a professor at Don Bosco University in El Salvador who has studied the Central American diaspora, said faltering economies, as well as fear, drive migrants from their homelands. “There aren’t jobs for everybody, and people fear for their life,” Rivas said. “So they go look for other places to live, if not in the US, then in Mexico, Panama, Costa Rica or Nicaragua.”

Yessica Alvarado, 20, said she fled El Salvador in October after she was attacked on her way to nursing school by gang members angry that her grandparents had refused to pay an extortion fee.

“It’s hard getting to Mexico, but not as hard as getting to the US,” Alvarado said.

On a recent afternoon, she sat on a sunny patio at a crowded Catholic migrant shelter in Tenosique chatting with a new acquaintance, a 27-year-old woman who escaped Honduras after her gang-member boyfriend beat her and threatened to kill her children. The shelter, La 72, was named for the 2010 massacre of 72 migrants in northeastern Mexico by members of a drug cartel.

Roots of violence

Even with its long-running drug war and a sliding peso, Mexico boasts a degree of safety and economic stability not seen in Honduras and El Salvador, which are among the poorest and most dangerous nations in the world. The roots of the violence there can be traced in part to the mass deportation of Los Angeles gang members to Central America in the 1990s. Experts say those countries aren’t prepared to reintegrate large numbers of new deportees.

Javier Eduardo Ferrera, 23, was deported to Honduras from North Carolina in September after police discovered cocaine in the car that he was driving.

Six days after he was released in the Honduran capital, Tegucigalpa, Ferrera left for Tenosique. He didn’t feel safe in Honduras, but he also didn’t want to risk ending up in prison if he were caught illegally crossing the US border. Immigrant deportees who are discovered again in the US can be charged with a federal crime punishable by up to two years in prison — a sentence Trump has threatened to increase to five years once he is in the White House.

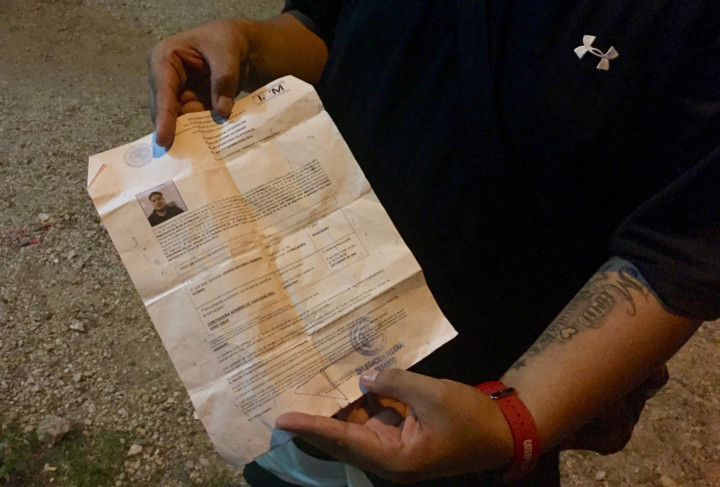

“Let’s wait and see whether Trump accomplishes his goals,” said Ferrera as he unfolded a crinkled document that gives him the right to temporarily stay in Mexico while his request for a humanitarian visa is processed. “If I can’t be there, I’d rather be here.”

A sleepy city built along a muddy river in the oil-rich state of Tabasco, Tenosique has long been a way station for migrants heading north. “La Bestia,” the infamous cargo train that has taken the limbs and lives of many migrants clinging to its roof on their way north, rolls through town.

Mexico crackdown

In the past, immigrants would spend only a few days in Tenosique, resting and waiting for the train, said teacher Gaspar Geronimo Gonzalez. “Now, many stay,” he said. Some families live in cinder-block shacks near the train station, while others sleep near the river. The town’s schools enrol well over 100 children from Honduras, who can be distinguished by their accents and Central American slang.

The migrants are staying despite Mexico’s crackdown on illegal immigration.

After tens of thousands of Central American children started streaming to the US border in 2014, generating headlines, President Barack Obama responded by requesting money from Congress to help improve conditions in Honduras and El Salvador. More quietly, his administration pressured Mexico to dramatically step up its border enforcement.

Parts of the southern states of Chiapas, Oaxaca and Tabasco now resemble border communities of Arizona and south Texas, with an influx of federal agents, militarised highway checkpoints and raids on hotels frequented by migrants.

The result? Mexico deported nearly 200,000 people last year, and from October 2014 to May 2015, they detained more Central American migrants than the US Border Patrol.