Maracay, Venezuela: The ballot for congressional elections, in which Venezuela’s ruling socialists face their stiffest challenge in 16 years, is dizzying enough in this industrial state, with more than two dozen parties on the ballot.

But most worrisome for incumbent Ismael Garcia, a fierce opponent of the deeply-unpopular socialist administration, is a 28-year-old parking lot attendant whose name will appear directly beside his on the ballot, under a nearly identical party title and logo.

He, too, is named Ismael Garcia. And three weeks ahead of the December 6 vote he has yet to make a public campaign appearance or even explain his platform.

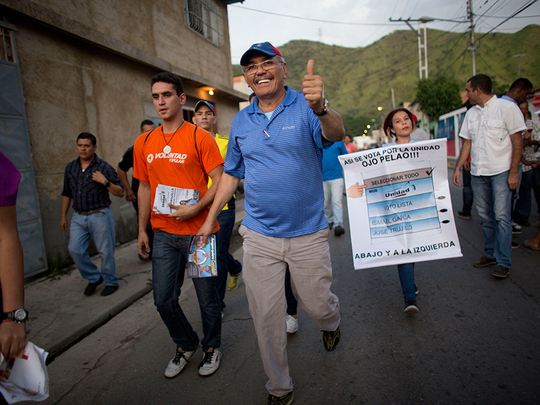

The result has been a bizarre campaign in which political veteran Ismael Garcia is mostly focused on helping voters identify him correctly when they go to the polls.

Opposition leaders say the race in Maracay is the most blatant example of a trick the ruling United Socialist Party of Venezuela, which has never lost a national election, is using in its effort to keep control of the National Assembly despite dismal poll ratings. With the world’s highest inflation, second-highest homicide rate, and a deepening recession, just 10 per cent of voters say they are happy with how things are going. Polling suggests the opposition could win control of the 165-seat congress by a landslide.

“It shows how crazy and desperate the government has become. They have fake candidates posing as the opposition in almost every contest in the country,” the older Garcia said, canvassing a neighbourhood of low-slung cinder block homes where he handed out flyers showing a mock-up of the ballot with a bright red arrow pointing to his name.

Supporters trailed the 61-year-old deputy, calling out the opposition’s slogan for the district, which it won by a slim margin in the last legislative elections: “Don’t get confused.”

It would be easy enough to make a mistake. The names of the Garcias’ parties are MUD Unity for the opposition and MIN Unity for the third-party.

Opposition figures have tried to unite their often-fragmented forces under the MUD Unity coalition to avoid splitting the anti-government vote. They say the government is trying to undercut that strategy with pseudo-opposition parties, chief among them the younger Garcia’s MIN, whose blue-coloured “Unity” symbol is almost identical to that of the MUD.

There are fewer than 150 adults in Venezuela named Ismael Garcia, according to state records. The young Garcia running in Maracay happens to work at the outdoor parking lot across from his rival’s office. The congressman’s staffers park their cars among stray dogs and rusty pickups there every day, but only realised this past week that their opponent was the heavyset young man with spiky gelled hair they see on their way out.

In his first public comments, the younger Garcia told The Associated Press that he can’t help it if the other Ismael Garcia — or as he called his opponent, “the old Ismael” — feels threatened.

“Everyone has a right to participate,” he said. “I can’t change my name.”

The small MIN Unity party had been part of the opposition’s MUD Unity coalition until this summer. But in August, a court ordered the party to replace its leaders, prompting coalition fears that a pro-government judicial system was being used to sabotage the opposition from within.

MUD expelled the party, and its choice of candidates — an array of novice and pro-government figures — has done nothing to dispel doubts.

The most recognisable of MIN Unity’s 61 aspirants is William Ojeda, a critic-turned-supporter of the late President Hugo Chavez, who initiated Venezuela’s socialist overhaul. Ojeda is a sitting congressman for the governing party, but he’s running in a hardscrabble part of Caracas as a MIN Unity candidate with the tagline, “We are the opposition.”

Ojeda denies he’s trying to confuse voters, and says MUD Unity is wasting time going after alternative parties when it should be focusing on the issues.

The head of the Washington-based Organisation of American States, Luis Almagro, recently accused Venezuela’s government of undermining the validity of the coming election through dirty dealing, including allowing MIN Unity to confuse voters. Other tactics that have drawn international criticism include the jailing of prominent opposition leaders who might otherwise win seats, the use of state media and official events to promote socialist candidates, and the redrawing of electoral districts to favour the ruling party.

In Maracay, the young Garcia said party leaders have barred him from speaking to the press because of security concerns and declined to explain who suggested three months ago that he run for office. His party opened its still mostly empty regional headquarters last month in a storefront the size of a two car-garage. It received its first shipment of branded baseball caps last week.

Garcia’s father, Argenio Garcia, said his son never participated in politics before this summer, but is having the time of his life. He dismissed charges of trickery as cynical attempts to undermine a legitimate candidate.

“That’s the old brand of politics,” he said. “Ismael is the future.”