Sao Paulo: Even under three blankets, Marcio Carvalho can’t stop shaking as he seeks shelter on the streets of Brazil’s biggest and richest city, Sao Paulo.

The teeming central streets of a city that is home to 20 million people are deserted at night except for members of the estimated 16,000 homeless population.

And while much of Brazil basks in tropical conditions, a chilly wave in the first days of the southern hemisphere winter has already claimed the lives of six people this month.

Among their few lifelines are volunteers from the aid group Anjos da Noite (Angels of the Night), who distribute food, water and blankets to the hundreds sleeping rough.

Carvalho, 41, who moved to Sao Paulo from the northeastern state of Bahia to improve his life, said he has been homeless for three years.

“I was working as a plumber, but I separated [from his wife] and I couldn’t stay in the house,” he said. “That’s how I ended up here.”

“Life on the street is very difficult and dangerous,” he added.

“I’ve been attacked several times. They’ve stolen my things and I’ve been very cold. I’ve had a drinking problem since I got here. To live on the street you have to drink.”

Cold is his latest enemy. Temperatures hit a 22-year low in early June to 3.5 degrees Celsius.

Homeless people and local media also accused security officers of stripping street people of their blankets and mattresses, prompting an outcry.

The leftist mayor, Fernando Haddad, initially said he didn’t want squatters occupying public squares with shacks and other gear, but later backtracked, making clear that personal belongings can’t be taken from the homeless.

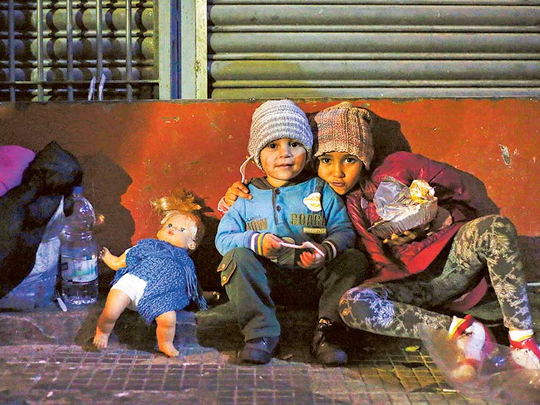

Sao Paulo’s population has risen around 0.7 per cent each year over the last decade-and-a-half, but the homeless number has gone up by almost 5 per cent annually. More than 80 per cent are men and 2.5 per cent children — 403 in all, according to the most recent study.

For those who fall through the cracks in Brazil’s crumbling economy, the landing is brutal, says Silvia Schor, an economics professor at Sao Paulo University.

“Survival conditions in Sao Paulo are cruel,” she said. “The city has inacceptable inequality, where income distribution means a lot of families can’t have their own house.”

Some two million residents live in slums called favelas, she added.

The severe recession has resulted in a 10 per cent increase in homeless numbers, says Kaka Ferreira, head of Anjos da Noite and a 27-year veteran of helping the city’s homeless.

“There are the unemployed, the sick, those with no family,” said Ferreira, who works at the agriculture ministry and devotes Saturdays to caring for the homeless along with a network of 80 others.

One of those gratefully collecting a plate of dinner recently was Marina Mayara da Silva, 19. Homeless with her two-year-old son and five months pregnant with another child, she sells sweets during the day.

“I’ve been here for two months because I couldn’t pay the rent anymore,” she said. “I used to live with my mother but there came a time when I couldn’t.”

Just along the street was Carvalho, wrapping himself in the blankets and saying he dreamed of being able to return to his one-time home in Bahia, where Brazil is tropical and even the winters are hot.