Robben Island: Nelson Mandela’s handwritten memoirs were smuggled off South Africa’s Robben Island to become an international bestseller after his release from 27 years in apartheid jail.

The manuscript’s risky passage is just one of the extraordinary journeys of the island’s books and the lengths taken to obtain, protect and share them in cells where learning and reading were celebrated.

“We weren’t allowed any reading material and I applied for permission to go to the library. They refused and eventually they agreed for me to have one book,” recalled Sonny Venkatrathnam who was jailed in the 1970s.

“It’s a problem to have one book and the only thing I could think of that would keep me going was ‘Shakespeare, Complete Works’ so I got that.”

The book was confiscated within weeks.

But a quick-thinking Venkatrathnam managed to get it back after convincing a warder it was “the Bible by William Shakespeare” and needed for church before disguising it as a religious text with pictures of gods from Diwali cards.

“My parents sent me greeting cards with Indian religious pictures on them so we cut them up and pasted [them] on the spine and on the outside. So that’s how it survived. I still have it like that,” the 78-year-old said.

The Shakespeare book will go on display at the British Museum on July 19, decades after it was passed from cell to cell with signatures dotting the texts that resonated most, such as Mandela’s sign-off next to Julius Caesar.

Reading was a lifeline inside the four walls and the thirst for books saw authors like Emile Zola and Jack London devoured alongside textbooks as libraries and teaching systems were set up among the political prisoners.

Apartheid’s idiosyncrasies meant that a version of Karl Marx’s Das Kapital made it past authorities, while a popular Indian cook book and the 19th century children’s classic Black Beauty were banned.

“They had a number of books that came in because the warders didn’t know who they were so everybody took advantage of it but we were also studying,” said Ahmad Kathrada, 82, who was the librarian in a section with Mandela.

“We were having people who were completely illiterate and they had to be taught ABC upwards, and eventually we can boast that nobody left Robben Island illiterate. They learned from one another.”

Sedick Isaacs was the librarian in his section when Capital, the English version of Das Kapital, arrived in a donation of old books.

The classic Marxism text made it through inspection — at a time when the apartheid regime had banned the local communist party — but an anatomy textbook was barred.

“It was a huge amount of amusement for me,” said Isaacs of being told: “Capital, oh its about money, you can have it.”

Isaacs, who went on to be head of biomedical informatics at Groote Schuur Hospital in Cape Town, wrote his first textbook on toilet paper in solitary confinement.

The mathematical concepts were penned out for a friend in the next cell in the tiny handwriting forced by shortages of writing materials.

“I left it in the toilet, he picked it up and took it in, studied it, did exercises. That’s how I wrote my first book: on toilet paper in small script.”

He even helped a warder with his studies.

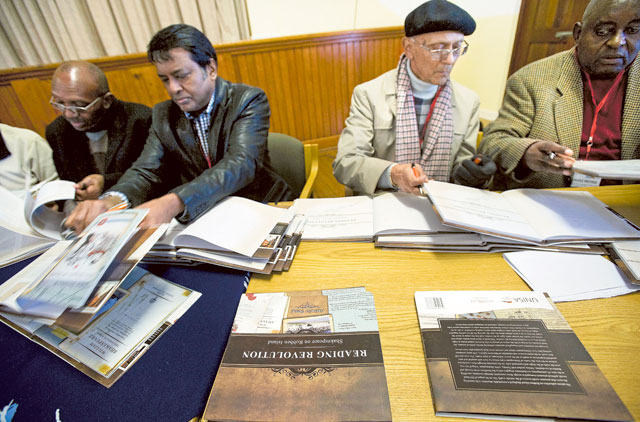

The unique literary insight into the anti-apartheid fight is captured in academic Ashwin Desai’s Reading Revolution, Shakespeare on Robben Island which was inspired by Venkatrathnam’s volume.

The book was circulated in an exercise that initially set out to collect signatures as a memento as the book circulated.

“I realised that this wasn’t just signing a book. These people thought about Shakespeare, they read Shakespeare, they were imbued with the sense of Shakespeare as they read it back onto local struggles,” said Desai.

The beauty and quest for a better life among the barbarism and lack of civility of the apartheid jailers was also a strong motivation.

“The real juxtaposition about this reading and literacy and the desire for knowledge was they were incarcerated because of apartheid, because they were simply inferior beings,” said Desai.

“Yet they thought and dreamed such big things and really improved their lives and had a constant quest for knowledge, and the warders who were white and supposedly of a superior race couldn’t be bothered.

That drive to read — and to learn with prisoners copying out textbooks in longhand — is a far cry from democratic South Africa which lacks a culture of reading in an education system that is sorely underperforming.

“It wasn’t just boredom,” said Marcus Solomons, who was jailed as a qualified teacher and bemoans current levels of literacy.

“Learning was always seen as an important aspect of freedom.”