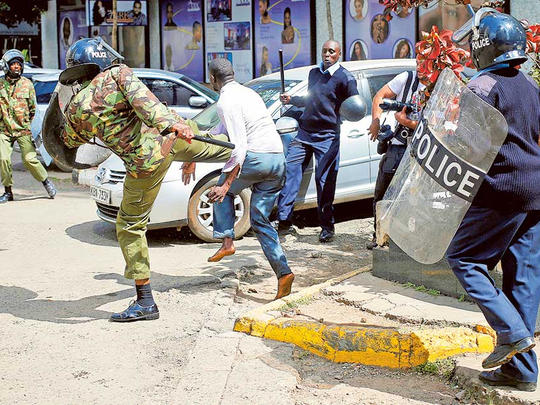

Nairobi: Police killings of Kenyans are on the rise, a Kenyan newspaper said on Sunday, as it published the country’s first comprehensive database detailing hundreds of such alleged killings in the past two years.

The Daily Nation, one of Kenya’s top selling newspapers, said it hoped the database covering 262 killings since the beginning of 2015 would help policymakers tackle police impunity.

Kenya’s struggle to track such killings has many parallels with the United States, the paper’s data editor Dorothy Otieno said. In both countries, the lack of official information about police killings prompted the national media to begin compiling their own statistics, she said.

In the United States, the Federal Bureau of Investigation announced last week it would begin tracking police use of deadly force, US media reported. But Kenyan authorities do not track police killings.

“The police are one of the major institutions in any country. They have the power of life and death. So the media has to play a watchdog role if the government isn’t tracking this [police killings],” Otieno said.

The database showed 121 Kenyans were killed by police in the first eight months of 2016, compared to 114 in the same period last year.

Cases included a 4-year-old girl shot near a demonstration, a 14-year-old girl whom two officers said attacked them and scores of young men in the slums described as criminals by police.

In most cases, police admitted the killings but said they were justified, Otieno said. In other cases, witnesses said police were involved.

Kenyan police say killings are mostly justified and deny impunity is a problem.

“There’s no policy in the government to kill anyone,” police spokesman Charles Owino said.

“Remember, there’s circumstances in law when officers are justified to use their firearms against people. And in order to protect life of the police officer, life of the citizen and even property and many other underlying circumstances.”

In June, hundreds of Kenyans demonstrated after human rights lawyer Willie Kimani, his client and their driver were shot dead after suing the police over a shooting.

Kenyan officials did not respond to questions about the number of cases submitted to or investigated by the country’s police oversight body, set up in 2012. The Independent Policing Oversight Authority’s website only mentions three cases where officers were charged for shooting civilians.

Mutuma Ruteere, the director of the Centre for Human Rights and Policy Studies in Kenya, said it was very rare for police to face punishment.

“There’s a large number of people who get killed [by the police] but who die, who get buried anonymously. Nothing is done. Over time that becomes a cancer, a virus, within the police,” he said.

Stephen Mwangi, a former resident of Mathare, one of the capital’s biggest slums, said he has lost many friends and a brother-in-law to police bullets.

Now he’s studying law to try to hold the police to account, he said. But individual families could not do it alone.

“If you’ve lost a son, you try and do advocacy by your own self. Maybe you can pull along two or three relatives. But then people have not come together to say: why the continuous and systematic killing of young men?”