Beirut: Three years into the revolt against his rule, Syrian President Bashar Al Assad is in a stronger position than ever before to quell the rebellion against his rule by Syrians who rose up to challenge his hold on power, first with peaceful protests and later with arms.

Aided by the steadfast support of his allies and the deepening disarray of his foes, Al Assad is pressing ahead with plans to be re-elected to a third seven-year term this summer while sustaining intense military pressure intended to crush his opponents.

The strategy is not new, but in recent months it has started to yield tangible progress in the form of slow but steady gains on several key fronts on the battlefield that call into question long-held perceptions of a stalemate.

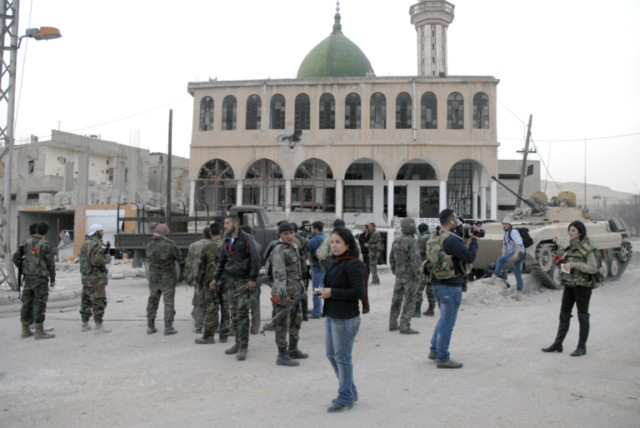

Most notably, the government has pushed the rebels back or squeezed them into isolated pockets in large swathes of the territory surrounding Damascus, diminishing prospects that the opposition will soon be in a position to seriously threaten the capital or topple the regime.

For those who joined the effort to unseat Al Assad three years ago, flush with the fervour of the Arab Spring protests sweeping the region, the realisation that the rebellion is faltering is “deeply depressing,” said Abu Emad, a student activist who has watched as the government has steadily crushed the armed rebellion in his hometown of Homs, once regarded as the epicentre of the revolt.

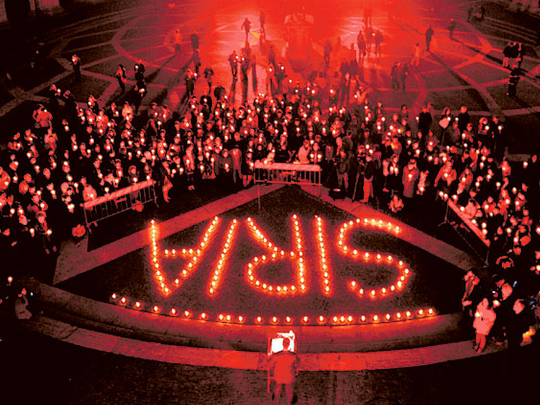

Saturday marked the third anniversary of the initially tentative antigovernment demonstrations that spiralled into civil war, and many Syrians are wondering whether the 140,000 deaths and the displacement of millions of people were worth the price, he said.

“More than ever there is no hope. Not on the ground and not politically,” Abu Emad said, using a pseudonym to protect his identity. “For the rebels to win, it will take a miracle.”

The extent of the progress has been such that Al Assad felt confident enough last week to travel 30km outside Damascus, through territory held by the rebels for much of the past two years. In the northeastern suburb of Adra, he visited displaced people, promised them aid and pledged to uphold the fight.

Meanwhile, the poorly armed and highly disorganised rebels have not launched a significant offensive or captured an important military facility since the fall of Menagh airbase in northern Aleppo province in the summer.

A much-anticipated rebel offensive in southern Syria, widely reported to be imminent after the collapse of peace talks in Geneva last month, has not materialised. Nor have new supplies of weapons from foreign backers that the Syrian opposition coalition said were promised last month.

Despite some scattered sightings of Chinese-made antitank weapons that were recorded and then posted on the Internet as YouTube videos, there is no indication of any influx of new weapons sufficient to make a difference to the balance of power on the ground, said Jeffry White, defence analyst at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy.

The chances that the government will be able to restore its authority over all the far-flung parts of the country that have slipped beyond its control seem remote. But the likelihood is growing that Al Assad will be able to pacify enough of the country to sustain his hold on power and claim victory, White said.

“The possibility of the regime winning in a real sense is there,” he said. “It depends on a lot of factors — that the regime continues to get support from [the Lebanese militia] Hezbollah and Iran, that there’s no outside intervention, and that the rebels don’t get better organised or new weaponry. But unless the rebels can change the situation on the ground in some way, the regime is going to keep grinding them down.”

Deepening rifts among the rebels have further enhanced the government’s prospects. A revolt in January by an assortment of diverse rebel groups against the Al Qaida-inspired Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (Isis) led to widespread bloodshed across northern Syria, most of which has been under rebel control for the past two years.

The rebel landscape has since continued to fragment. Al Qaida’s central command repudiated Isis, triggering a rift between that group and Al Qaida’s main Syrian affiliate, Jabhat Al Nusra, that has erupted in fighting in the east of the country. The mainstream Supreme Military Council, backed by the US, has split into two feuding camps after the ouster of its commander, Gen. Salim Idriss.

The divisions have diverted resources and attention from the effort to dislodge Al Assad. Since January, 3,000 rebel fighters on both sides have been killed, according to the Britain-based Syrian Observatory for Human Rights.

Liwa Al Tawheed, the biggest rebel force in Aleppo, lost 500 men in those weeks, compared with 1,300 in two years of fighting government forces, according to a logistician with the brigade, who spoke on the condition of anonymity. His brigade is deeply divided over the confrontation with Isis, with some battalions in favour of fighting the extremists and others opposed, and the subject is sensitive even within his own unit.

“It has taken a heavy toll, and the regime is taking full advantage,” he said of the rebel rifts. “Now we are in danger of losing Aleppo.”

Meanwhile, preparations are gathering pace in Damascus for presidential elections due by July under the terms of Syria’s current constitution. A new election law passed by Syria’s parliament last week permits challengers to Al Assad for the first time — but under restrictions that will preclude serious opposition contenders. Candidates must secure support from the parliament, which is dominated by Al Assad’s Baath Party, and have remained in residence in Syria for the past 10 years.

UN mediator Lakhdar Brahimi warned members of the Security Council in a briefing Thursday that such an election would jeopardise prospects for a resumption of the failed Geneva peace talks, which underpin the Obama administration’s Syria policy.

“If there is an election, then my suspicion is that the opposition, all the oppositions, will probably not be interested in talking to the government,” he told reporters after the briefing.

The government, however, has displayed no desire to talk to its opponents, and the failure of the Geneva talks also revealed that Syria’s ally Russia is disinclined to pressure Assad to do so. The attention of the US and other Western powers has been diverted by the crisis in Ukraine, and the opposition’s main Arab allies, Saudi Arabia and Qatar, are consumed with disputes of their own.

In an interview this week with the Lebanese daily Al Akhbar, the Russian ambassador to Lebanon boasted that Russia had succeeded in blocking UN action against Syria at the Security Council, and he predicted an Assad victory.

“The Syrian army is making major progress on the ground,” he said. “The tide of the war cannot be reversed anymore.”