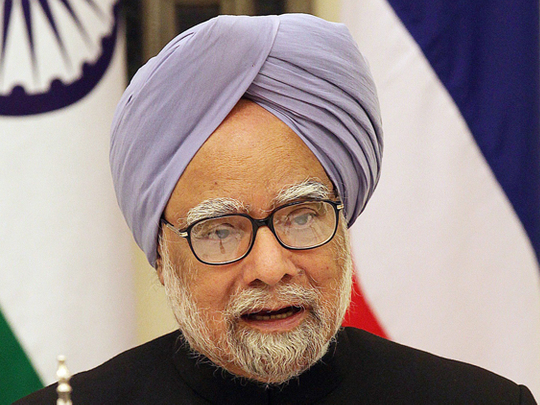

Politics was never his cup of tea. But former prime minister late P.V. Narasimha Rao had closely studied Manmohan Singh’s track record as the Reserve Bank of India governor and as the deputy chairperson of the Planning Commission and was convinced that Manmohan was indeed the man he needed to change the form and substance of Indian economy – lock, stock and barrel. In fact, when word first reached Manmohan that the ‘PM’ had included him on his list of cabinet ministers and that he wanted him to be the nation’s next finance minister, he ignored it as some kind of a joke making its rounds in the corridors of South Block.

Speaking to BBC correspondent Mark Tully, Manmohan once said: “On the day (Rao) was formulating his cabinet, he sent his principal secretary to me, saying: ‘The PM would like you to become the minister of finance’. I didn’t take it seriously. He (Rao) eventually tracked me down the next morning, rather angry, and demanded that I get dressed up and come to Rashtrapati Bhavan [presidential palace] for the swearing in. So that’s how I started in politics”.

After Congress lost the elections in 1996, Manmohan was named the leader of the opposition in Rajya Sabha and right through the Vajpayee days, from 1998-2004, he held on to that position.

The year 2004 marked a watershed in his career as Congress president Sonia Gandhi anointed him to be the nation’s next prime minister after the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance defeated the Atal Bihari Vajpayee-led National Democratic Alliance government at the Centre.

While an unrelenting opposition raised the bogey of Sonia’s Italian origin as ground for disqualifying her candidature for prime minister, firebrand Bharatiya Janata Party leader Sushma Swaraj swore to tonsure her head should a “foreigner” like Sonia become the next PM. To push such an unsavoury controversy to the back burner for good, Sonia came up with the masterstroke of nominating Manmohan as PM – keeping in mind that son and first-time parliamentarian Rahul was all too inexperienced and would need a few more years of ripening in the rough and tumble of Indian politics.

From finance minister to leader of the opposition to being the PM, Manmohan’s career graph has scaled many a height, but there is no doubt that it was as the nation’s finance minister that he made the biggest impact and ironically, it took a non-Nehru/Gandhi Congress PM like ‘chanakya’ Rao to get the best out of an Oxford-Cambridge scholar.

The ‘lame duck’ PM:

Grappling with a dual power-centre in government, Manmohan Singh’s days at the PMO (prime minister’s office) were often like a self-inflicted torture course. Right through his tenure at 7, Race Course Road (the prime minister’s official residence), Manmohan had to live and work under the looming shadow of dynastic politics, with the baggage of the Nehru-Gandhi family name hanging like an albatross round his neck. He had to comply with the thankless responsibility of keeping Sonia’s dreams alive of having son Rahul anointed as the PM at some point; he had to swallow the bitter pill of having to ignore Rahul’s pointed barbs at his government, time and again, as the ‘prince’ sought to emerge as the Congress party’s voice of conscience; and he also had to play a doting guardian to the whims and wishes of truant coalition allies, whose illogical demands at times made a travesty of a prime minister’s prudence.

True, Sonia offered prime ministership to Manmohan on a platter, but it is equally true that playing second-fiddle to the Gandhi brand name and following diktats from 10 Janpath (Sonia’s residence) with an unquestioned allegiance for 10 years have sucked out whatever semblance of an independent-minded individual there ever was in Manmohan.

Just as he couldn’t say ‘no’ to Sonia when she wanted him to be the ‘chief executive officer’ (CEO) of the UPA government, similarly he couldn’t put his foot down when Sonia’s obsession to paint the government with a socialist brush ran contradictory to the principles of economic ‘glasnost’ and ‘perestroika’ (openness and restructuring) that ‘Manmohanomics’ had taught India to embrace through the revolutionary Union Budget of 1991.

Allowing foreign direct investment in multi-brand retail and opening up the aviation sector to foreign investers were only some of the patchworks of remedy that Manmohan was allowed to apply to a wound of gangrenous proportion.

Having someone like Pranab Mukherjee around as the finance minister made matters worse for him. Like Sonia, Mukherjee’s penchant for schemes like farm loan waiver and indefinitely delaying foreign direct investment in retail kept the government perennially hamstrung with a socialist baggage.

The man who had turned Indian economy on its head was reduced to a silent observer as the Indian rupee nose-dived to historic lows and inflation pushed the common man tantalisingly close to the edge of the cliff.

With such demanding allies like DMK and Trinamool Congress around, PM Manmohan could well have done without enemies! While the government dithered in taking action against ministers like A. Raja in the telecom scam, just to keep the equations with DMK unaltered, Manmohan had to accept a rollback of railway fares simply to keep Mamata Banerjee in good humour.

The result of such ready and wholesale compliance with the compulsions of coalition politics made Manmohan come across as a weak PM, whose hold over the government was not just brittle but terminally flawed.

The slew of scams that rocked UPA 2 could perhaps have been averted had Manmohan said ‘enough is enough’ at some point. He ought to have realised that he might have been tasked with the thankless job of keeping the seat warm for Rahul to step in at an appropriate time, but in so doing, he had compromised with the sanctity of the PMO and put his own reputation as ‘Mr Clean’ on the line. Tomorrow, if a new government at the Centre tries to heckle Manmohan over allegations of foul play in the allocation of coal blocks, will Rahul or Sonia step in to defend him? Your guess is as good as mine!

Technocrat the world loves:

‘World’s envy, India’s pride.’ No, that won’t be a misnomer so far as the economist Dr Manmohan Singh is concerned. His understanding of the subject and his stints as RBI governor, Planning Commission deputy chairperson and most of all as the Union finance minister caught the attention of world leaders like former US president George W. Bush and German Chancellor Angela Merkel.

With the global meltdown at its peak in 2008-09, Manmohan was the ‘go-to’ man for many a statesman like US President Barack Obama or former British premier Tony Blair who would just pick up the phone and dial New Delhi for a second opinion and some dispassionate suggestions.

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe heaps wholesome praise on Manmohan , referring to him as a “mentor”, while Obama spontaneously slips out of his presidential protocol and walks up to the Indian prime minister’s car at the White House portico to welcome him.

Such is the kind of personal rapport that Manmohan has struck and that has largely been possible not because of any prime ministerial halo, but by being a technocrat and an academic of the highest order.

If only he had a similar charisma as the premier of the world’s largest democracy!

Profile

- Name: Manmohan Singh

- Born: September 26, 1932

- Place of birth: Gah, Punjab (now part of Pakistan)

- Wife: Gursharan Kaur

- Children: Upinder, Daman and Amrit.

- Alma mater: Punjab University, Chandigarh; St John’s College, Cambridge;

- Nuffield College, Oxford.

- Employment recital: Professor of International Trade, Delhi School of Economics; Governor, Reserve Bank of India; Deputy Chairperson, Planning

- Commission; Economic Adviser to the Prime Minister (V.P. Singh); Chairman, Union Public Service Commission; Chairman, University Grants Commission.

- Ministerial portfolio: Union Minister of Finance (1991-1996); Prime Minister (2004 to present ).

- Personal assets: Rs50 million (Dh3.67 million). This includes an apartment in New Delhi worth Rs8.8 million.