What started in the 1930s in Europe and the US to stimulate trade and business in underdeveloped regions through tax and tariff incentives was a hugely successful concept — free trade zones.

They were mainly located at or around crucial infrastructure hubs such as airports, ports, national frontiers and industrial centres of host countries that acted as fertile grounds for the implementation of liberal market economy principles. Their significance rose tremendously after the end of the Cold War when the world’s division into countries adhering to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade in the West and the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance in the Eastern bloc was broken up.

The beginning

What followed was the creation of the World Trade Organisation (WTO) and the mushrooming of bilateral and multilateral free trade zones all across the globe. As of today, there are more than 3,000 free trade zones over 110 countries. And together with additional bilateral free trade agreements and a number of other international agreements, mainly facilitated by the WTO, global trade has got a much-required boost.

“The main objectives of governments in establishing free trade zones are to encourage investment and job creation,” says William Methenitis, Global Director of International Trade and Development at consultancy EY.

“By easing barriers to trade, governments seek to attract business that could be conducted effectively from other countries. While benefits for businesses can differ by country, there are common advantages that include duty exemptions, tariff and tax reliefs, supply chain benefits, easy business structures, and currency exchange benefits.”

Over time, it turned out that those benefits could be increased by expanding free trade zones with more participating economies and streamlining their structure across several nations over much larger areas.

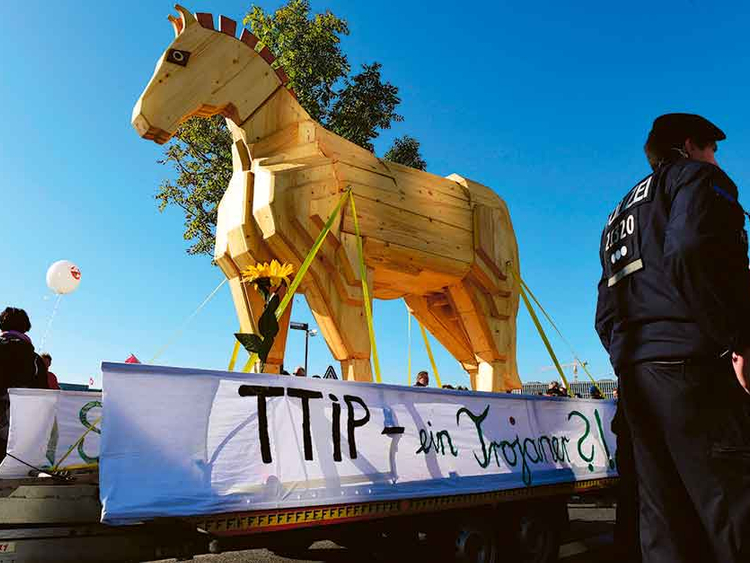

Today, the concept of multilateral trade agreements is culminating in the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) between the US and 11 other countries including Japan, Australia, Malaysia and Mexico, and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) between the US and the European Union (EU). However, not everyone in the EU is happy with the negotiations over TTIP.

Widespread protests in France over unregulated free trade that they say the TTIP may come to define culminated in French president Francois Hollande threatening to pull out of the deal early this week. Germany, that has been seeing anti-TTIP protests since late last year, saw fresh protests this week during US president Barack Obama’s visit.

Too many, too soon

Heribert Dieter, Senior Fellow at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP), calls what he feels to be a “mushrooming” of many preferential trade agreements “puzzling”, as they have grown so fast and became so powerful that they started to undermine the envisaged multilateral system of the WTO and redivide the world into new economic blocs.

“This is best shown by the fact that few free trade projects have been welcomed more enthusiastically than the TTIP and the TPP, which both exclude the main emerging powers, namely China, Russia, India and Brazil,” says Dieter. “At the same time, the excitement over the WTO has evaporated.”

The impact of this development is obvious. The TTIP, for example, is far more than a trade pact, as it carries the potential to strengthen the Euro-Atlantic geopolitical leverage as such, creating a new global economic order between the EU and the US. Many emerging regions such as the Middle East, Africa, and Western, Central and South Asia will not be a part.

“It’s an opportunity to cement the Euro-Atlantic geopolitical alliance and restore faith in the Western model of market economies,” says Jacob Schrot, founder of non-profit organisation Young Transatlantic Initiative and a popular advocate of TTIP in Germany.

“In Germany, some 600,000 jobs depend on this pact, and across the Atlantic, it’s 15 million.”

But the US pursues its own agenda if both TTIP and TPP are taken together. “With both agreements in place, the US will be at the centre of a free trade zone covering nearly two-thirds of the global economy,” wrote US Trade Representative Michael Froman in an article in Foreign Policy magazine.

“Combined with all of the strengths that already make the US an attractive place to invest and do business, we will be one step closer to becoming the world’s production platform of choice, further increasing our economic strength and influence.”

The Middle East and the new economic world order

The Middle East and North Africa are left out of the two big trade agreements, TTIP and TTP, as are India, China, Brazil and Russia.

This means — particularly in the wake of dwindling oil prices that bring with them the need for economic and structural change — that the region will have to pursue the deepening of its existing agreements such as the Greater Arab Free Trade Area or trade relations within the GCC and enhance its participation in the US Middle East Free Trade Area and the European Union-Mediterranean Free Trade Area.

The latter could bring about positive outcomes from the TTP. Some parts of the Middle East and Western Asia are also enticed by alternative trade initiatives such as the new Silk Road Economic Belt project by China or the Eurasian Economic Union spearheaded by Russia.