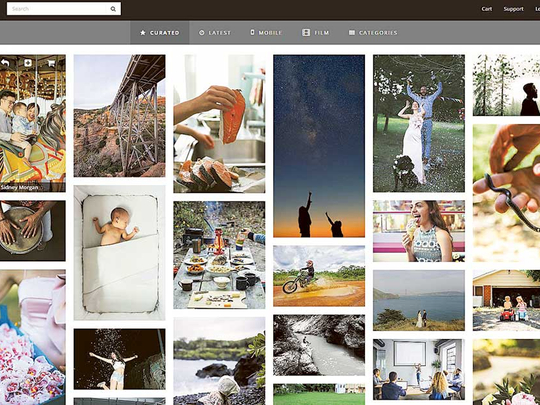

New York: The arresting images on Stocksy.com are far from the standard fare found on many stock photography sites. Colourful portraits, unexpected compositions and playful shots greet visitors.

The most distinguishing feature, however, may be the structure of the site’s owner, Stocksy United: It is a cooperative, owned and governed by the photographers who contribute their work. Every Stocksy photographer owns a share of the company, with voting rights. And most of the money from sales of their work goes into their pockets rather than toward the billion-dollar valuations pursued by many venture-backed start-ups.

Stocksy was founded in 2013 by Brian Livingstone and Brianna Wettlaufer, the core team behind iStockphoto, which in 2000 pioneered the idea of selling stock photos online in exchange for small fees. (Livingstone was the founder and Wettlaufer, the vice-president of development and employee No. 4). IStock – which billed itself as “by creatives, for creatives” – caught the attention of Getty Images, which acquired it in 2006 for $50 million (Dh183.6 million).

Livingstone and Wettlaufer, who are now married, grew dismayed as the community spirit they had cultivated and the royalties photographers received began to erode under the new ownership. Like many artists in the digital age, their photographer friends grumbled that they were being underpaid and exploited by online sites.

“Everyone had the same story,” Wettlaufer said. “They were feeling disenfranchised. They weren’t creatively inspired anymore. The magic was gone.”

So using money from the sale of iStock to Getty, she and Livingstone set out to create Stocksy, paying photographers 50 to 75 per cent of sales. That is well above the going rate of 15 to 45 per cent that is typical in the stock photography field. The company also distributes 90 per cent of its profit at the end of each year among its photographers.

“We realised we could do it differently this time,” said Wettlaufer, who took over the chief executive role in 2014. “We could enter the market with a model that ensured artists were treated fairly and ethically.”

Stocksy is part of a new wave of start-ups that are borrowing the tools of Silicon Valley to create a more genuine “sharing” economy that rewards the individuals generating the value.

According to a recent Pew poll, 72 per cent of Americans have used some sort of shared or on-demand service, whether it’s Uber for rides or TaskRabbit for things as diverse as dog walking and household chores. But there has been much criticism that, after the platforms take their cut and the workers pay for expenses, little may trickle down to those doing the actual work.

And, although many workers appreciate the flexibility to schedule their own hours, they don’t have the same protections and benefits as full-time employees. Evidence suggests that the shift to on-demand labour may increase economic vulnerability for the roughly one-third of Americans who are contingent workers.

In just a few years, Stocksy has grown to 900 photographer-members, carefully selected from more than 10,000 applications. It has 20 full-time employees at its headquarters in Victoria, British Columbia, and another five contractors who work remotely.

Hugh Sitton, a photographer based in Britain, is typical of the quality of talent Stocksy is attracting. His profile page on Stocksy showcases his globe-trotting style, from portraits of a Samburu tribesman in Kenya to Vietnamese women in a pond of lotus flowers. His images have sold to clients ranging from travel sites to financial institutions.

“The stock photography industry has become much more competitive, and many photographers are definitely struggling due to the current price war for images,” he said.

He said he found the Stocky site easy to upload photos, create a portfolio page and track his sales. And he likes the fact that any member of the cooperative can submit an idea for discussion or to be put to a vote.

When Wettlaufer and Livingstone set out to create Stocksy, they considered making it a non-profit organisation, but decided to form a digital cooperative (“Think more artist respect and support, less patchouli,” reads the website).

Stocksy is what’s known as a multi-stakeholder cooperative, with three classes of shares: one for executives, one for staff and a third class for photographers. There is no fee to join or annual dues; members pay just $1 for their share of stock. That collaborative approach has helped the upstart thrive in a crowded and competitive market.

Stocksy’s customers include major media names, such as the magazines Glamour and Elle, as well as start-ups and small businesses.

Vanessa Bruce said she was mesmerised when she came across an ad for Stocksy while flipping through a magazine. The images were “clean but quirky,” said Bruce, who was then a brand manager for ReferralMob, a job referral site. She licensed several Stocksy photos, including one of a dog and a dinosaur that inspired language for a ReferralMob ad: “Match your friends with unique opportunities,” the ad read.

That Stocksy was owned by photographers was even more satisfying. “That made us love them even more,” said Bruce, who is now a co-founder of a marketing and branding agency called Six Things.

Stocksy’s revenue doubled last year to $7.9 million. More than half, $4.3 million, was paid out in royalties. After that and other operational costs, Stocksy last year generated its first “surplus revenue,” or what is akin to profit at co-ops. This allowed it to pay a dividend to members for the first time, totalling $200,000.

Stocksy’s success may be a model for other digital cooperatives taking on behemoths in other industries. In San Francisco, Loconomics has started an online cooperative for professional services, from massage to graphic design, comparable to TaskRabbit.

Others are developing profit-sharing platforms for filmmakers, domestic workers, taxi drivers and musicians.

Some business models are involving workers more but forgoing the co-op route. Juno, a new on-demand car service app being tested in New York, plans to take a smaller cut of the fares and will set aside half of its founding shares for its drivers.

These smaller upstarts, however, face an uphill battle against heavily funded and entrenched competitors that have benefited from a self-enforcing “network effect.” A large user base gives companies like Uber more prominence, and thus more visibility. The cooperatives also don’t have the billions in venture capital backing them.

“There’s no way we can ever outspend those giant companies,” Wettlaufer acknowledged.

But some consumers, workers and regulators are starting to push back against what they see as abuses in the sharing economy. Various lawsuits and proposed laws are aimed at protecting workers, and the descriptions of users’ negative experiences that have become widely publicised have hurt the image of the once-vaunted technology unicorns.

The flow of venture capital that subsidised rock-bottom consumer prices is drying up, and some companies are raising money at lower valuations than they did previously.

Even iStock’s new owner, Getty Images, has struggled under $2.6 billion in debt that it was saddled with after it was acquired in 2012 by the Carlyle Group, a private equity firm.

There is room for cooperatives to flourish alongside big competitors, some in the industry say. Craig Shapiro, founder and managing partner at Collaborative Fund, a venture firm based in New York, has backed highflying on-demand platforms including TaskRabbit and Lyft. But he said he saw the selling point of co-ops.

“As a shareholder in some of these businesses, I am hopeful that they’ll all be successful,” Shapiro said. “But models that reward the members who are generating value will ultimately win.”

Against this backdrop, Stocksy’s leaders see opportunity to grow. The company plans to add another 100 photographers by the end of the year and expand into video. It hopes that having quality photographers who are part owners will help it stand apart from the competition.

“It’s loving what we do,” Wettlaufer said.