Volkswagen’s decision to nominate a long-serving executive as chairman has once more highlighted the carmaker’s corporate governance and culture, which some experts argue were a root cause of the diesel-emissions scandal.

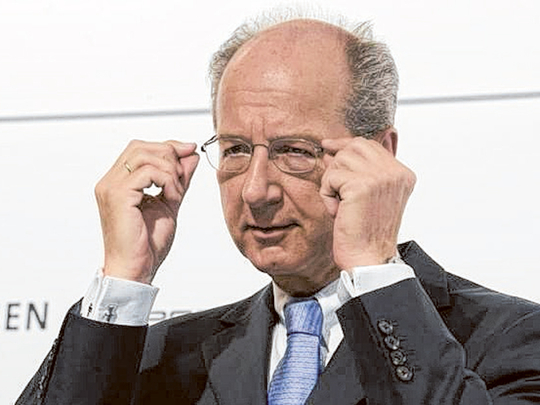

Top directors announced that Hans-Dieter Potsch, VW’s chief financial officer since 2003, would become chairman in the coming weeks, filling the spot vacated by patriarch Ferdinand Piech, who resigned in April. Hans-Christoph Hirt, a director of Hermes Equity Ownership Services, an adviser to pension fund investors in companies including VW, said the appointment created a “serious conflict of interest”.

“[Potsch] was a key VW executive for more than a decade and under German law the management board has a collective responsibility ... The lawyers will surely demand that he recuse himself from any supervisory board meetings when management’s role is discussed,” Hirt said.

VW’s response has been compared with the way Siemens dealt with a huge bribery scandal in 2006. For the first time in its 150-year history the German engineering conglomerate appointed an outside chairman (Gerhard Cromme from ThyssenKrupp) and chief executive (Peter Loscher from Merck in the US).

Together they transformed Siemens’s culture and Cromme took legal action against former Siemens executives for not stopping the bribery. “How is Potsch supposed to do that?” surmised Hirt.

VW has admitted installing software in engines over several years so they passed laboratory emission tests but belched out dangerous nitrogen oxides when on the road. Martin Winterkorn resigned last month as chief executive, insisting he knew nothing of the cheating, which analysts fear could cost VW billions of euros in fines, lawsuits and recall costs.

Assisted by a US law firm, VW has launched an internal investigation and reported the wrongdoing to prosecutors.

However, governance experts argue the cheating was predictable because of VW’s lax boardroom controls and peculiar corporate culture. “The scandal clearly also has to do with structural issues at VW ... There have been warnings about VW’s corporate governance for years, but they didn’t take it to heart and now you see the result,” says Alexander Juschus, director at IVOX, the German proxy adviser.

Even before the diesel scandal, VW’s shares traded at a discount to other carmakers partly because of governance concerns. A former chairman of a large German industrial company says “Germany has corporate governance problems but VW has long been uniquely awful”.

A key weakness at VW remains the lack of diversity of opinion and expertise on the company’s supervisory board, experts say. The 20-member council of directors — whose membership is equally divided between shareholder and worker representatives — is responsible for hiring and firing executives, providing advice to management and monitoring their actions.

Yet 17 of the 20 members are either German or Austrian and the board of directors has only one truly independent voice — Annika Falkengren, chief executive of Swedish bank SEB.

Many of the remaining directors are representatives of the three largest shareholders — the Porsche and Piech families, the State of Lower Saxony and Qatar. In 2012 VW appointed Ursula Piech — a former kindergarten teacher and the wife of Piech — to its supervisory board. Both have since resigned.

“VW’s supervisory board is short of people with relevant experience and skills and — significantly — independence,” says Hirt. External investors have only 12 per cent of the voting shares and therefore “can’t change anything”, according to Juschus.

Directors at other German companies often meet investors but their access to Piech was very limited.

It wasn’t always that way. Ten years ago VW’s supervisory board still boasted external luminaries including Cromme, the author of Germany’s corporate governance code. But Cromme quit VW’s board in 2006 when Piech used votes from workers to push through a trade unionist as head of personnel, against the wishes of some shareholder representatives on the board.

The influence of employees at VW remains far greater than at any other major German company. The carmaker’s response to the diesel scandal emissions crisis has been steered by a small committee of top directors and three of the five members are labour representatives.

Ferdinand Dudenhoffer, automotive expert at the university of Duisburg-Essen, describes Bernd Osterloh, VW’s chief labour representative, as a kind of “co-manager” who now “dominates the supervisory board”.

Due to a lack of suitable candidates among the shareholder representatives on the board, VW’s interim chairman is currently Berthold Huber, a former head of the IG Metall trade union.

Although these cosy relations have some advantages — in times of crisis, management can more easily get the backing they need to push through changes such as cost cuts — critics say they represent a Faustian pact in which managers protect German jobs, in return for support.

VW has almost 600,000 employees but its management board is staffed entirely by men. Under Piech and Winterkorn, decision-making at VW was highly centralised and more junior managers were frightened to speak their mind.

In the aftermath of the diesel-emissions scandal, Osterloh has urged to create a culture where problems are “not concealed but are openly communicated to superiors”.

Following his appointment as VW chief executive, Matthias Muller pledged to “develop and implement the most stringent compliance and governance standards in our industry”.

Others recall that previous crises at VW — including a prostitutes and bribery scandal in 2006 — did not deliver real reform. “If VW doesn’t change now then they will never do it. It really depends on the three big shareholders — whether they are willing to reform,” says Juschus. “I have my doubts.”

Financial Times