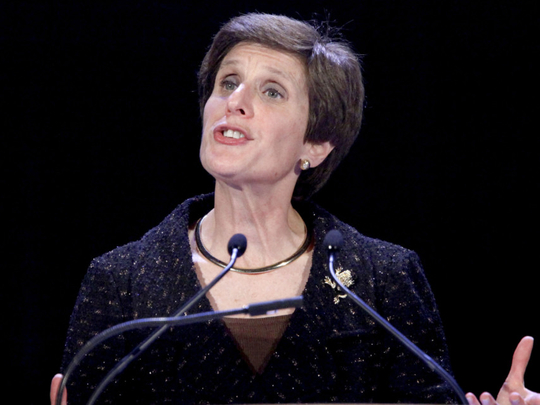

Irene Rosenfeld, the chief executive of the snack food maker Mondelēz International, wandered through an ocean of processed foods one day recently, admiring her handiwork. The centre aisles of Mariano’s, an upscale supermarket near the Mondelēz headquarters, were stuffed with her company’s creations — Oreos, Wheat Thins and Ritz crackers.

As Rosenfeld stepped down as CEO after 11 years leading Mondelēz and its predecessor, she reminisced about a career spent trying to increase sales of cookies, candies and chips — and reflected on shifting consumer preferences that are demanding fresher, healthier foods than the ones she championed for so long. “I set out to create the world’s greatest snacking company,” she said. “But the legacy I’m most proud of is the ethos of this company, where individuals care about one another, they have each other’s back and they care about the world they live in.”

A 36-year veteran of big food companies, Rosenfeld took over as chief executive of Kraft Foods in 2006, acquired the British chocolatier Cadbury in 2010 through a hostile takeover, and split the company in two in 2012, creating Mondelēz. With $26 billion in annual sales and a market value of $63 billion, Mondelēz makes cupboard staples including Triscuits, Fig Newtons and Oreos, as well as dozens of chocolate and biscuit brands sold around the world.

Rosenfeld has kept up with the move toward globalisation, shifting away from the US and Europe and into emerging markets like Asia and Latin America, and introducing some healthier options. Along the way, she tangled with the British government, Warren Buffett and hedge fund activists including William A. Ackman and Nelson Peltz — not to mention the groups advocating for healthier foods in a much more health-conscious era.

By many measures, she was successful. Through acquisitions, spin-offs, disposals and dividends, she made billions of dollars for investors and a fortune for herself.

“She has focused on building shareholder value successfully by increasing margins with no dewy-eyed nostalgia over changing conditions,” said Jeffrey Sonnenfeld, a professor at the Yale School of Management. “She is an honourable leader who has survived an industry going through wrenching change and pressure from tough, vocal short-term activists.”

Rosenfeld was richly rewarded for her work. In her 11 years as CEO — first of Kraft Foods and now of Mondelēz — she has made about $231 million, according to Equilar. That does not include her compensation before 2006, or a retirement package, yet to be announced, that will surely be worth many millions more.

But as consumer tastes change, millennials are embracing upstart brands. Health concerns over processed foods are on the rise. Mondelēz sales were falling until the company reported an uptick last month, and the stock has barely budged in the last year.

Rosenfeld and the company say it was her decision to step down. “I’ve been doing this for over a decade,” Rosenfeld said. “Ever since I announced my retirement, I’ve been sleeping better.”

But the board was ready for change and began looking for her replacement in the spring. Dirk Van de Put, head of frozen food maker McCain Foods, will take over Mondelēz, leaving one fewer woman at the helm of a major company. “It’s painful for her to leave,” said Lois Juliber, who is on the board of Mondelēz. “I’m not sure she feels like she feels like the job is done yet.”

Born in New York City in 1953, Rosenfeld grew up on Long Island and went to college at Cornell, where she played basketball and gained advanced degrees in business, and marketing and statistics. After school, she went to work for an advertising firm, and then in 1981 joined General Foods, which made Oscar Mayer meats and Maxwell House coffee. General Foods was acquired by cigarette maker Philip Morris in 1989, which at that time also owned Kraft.

As her responsibilities expanded to overseeing consumer research, beverages and desserts, she learnt some key lessons that would inform her career. For one, she said, it was important to invest and innovate, which wasn’t easy as a subsidiary of a cigarette maker when tobacco makers were paying big colonies for health related lawsuits.

“The parent company was pressuring the food business to deliver cash,” she said.

But perhaps the most important truth she came to understand was an obvious one: People like to eat cookies. They like to eat chips. They like to snack.

“It’s an exceptionally impulse-driven set of products, so consumption is expandable,” she said. “The more displays we would put up in a store like this, the more products we would sell.”

But with those sales successes came the negative connotations associated with peddling “junk food” to a nation of consumers who increasingly sought out healthier and fresher options. Noting that “there is an accelerating interest in well-being everywhere in the world,” Rosenfeld said Mondelēz took the issue seriously, removing genetically modified ingredients from Triscuits, offering resealable packages of Oreos and introducing relatively healthy brands like Véa, a new biscuit line.

Kraft went public in 2001 and Rosenfeld ran the Canadian business, the operations group, and, by 2002, all of North America. But the higher she rose, the fewer women there were by her side.

Rosenfeld said she did experience sexism on the job, but declined to provide details. “I grew up in the industry at a time when there weren’t that many women and in key positions,” she said. “There was always a sense that we needed to work just a little harder, and we had to stand up for ourselves in the face of managers who weren’t as respectful as they ought to have been.”

Rosenfeld said she thought her athleticism gave her an edge, and that men were impressed that she could often beat them at tennis and golf during company retreats. “I held my own in a lot of these corporate outings,” she said. “I came with a sharply honed competitive instinct.”

In the wake of a flurry of sexual harassment revelations in the business world, Rosenfeld encouraged female professionals to have a zero-tolerance policy for abuse. “Do what in your heart you know is right,” she said. “It is easy to get caught up in your ambitions, but no job is worth not being true to yourself.”

And Rosenfeld said she had championed women in the workplace. Fourteen of her employees have gone on to become CEOs of major companies, including Denise Morrison of Campbell Soup and Michele Buck of Hershey. In 2004, after 23 years at the same company, Rosenfeld left Kraft to run the Frito-Lay division of PepsiCo.

She would have stayed there longer, but in 2006 she got an offer to run her old company, and became the CEO of Kraft Foods. At the time, Kraft was dominated by big American brands like Velveeta and its eponymous boxed Macaroni & Cheese.

Rosenfeld set out to change that. She acquired Lu, a cookie maker with a big business in Europe. And she set her eyes on Cadbury, the British chocolatier.

After waiting and watching for two years, Rosenfeld approached Cadbury with a hostile takeover bid in 2009. The company resisted, depicting her as a greedy outsider, and appealed to the British public to protect a cherished national brand. “In an effort to defend themselves, the company draped itself in the Union Jack,” she said.

To attend meetings during the takeover campaign, she would land at airports outside London so as not to be detected, and check into hotels using the pseudonym Debbie Friedman.

Some Kraft shareholders, including Warren Buffett, disapproved of the acquisition. “One of the reasons Buffett was concerned was he didn’t want to be diluted,” she said.

But Rosenfeld was undeterred, and the $20 billion deal got done. At a management meeting in July of 2010, Rosenfeld said, she surveyed the room and realised she was looking at two companies.

So in 2011, she announced the company would be halved — with Kraft focused on savoury US staples, and a new company, Mondelēz, focused on a global snacks business. (The name is a Romance language mash-up suggesting a world — “monde” — that’s delicious.)

Mondelēz stock has risen more than 50 per cent over the last five years, but hedge fund managers like Ackman and Peltz are rarely satisfied. Rosenfeld has dealt with both men for years, and Peltz now sits on the Mondelēz board.

She grudgingly accepts that activists are here to stay, but said “there is a short-term orientation that is not necessarily healthy for sustainable businesses.”

As her career winds down, Rosenfeld — who earned a fortune breaking glass ceilings and shaped the fates of so many important brands — remains a company loyalist to the end. She even sees the steady progress of women in the workplace — something she has championed — as a tail wind for her business.

“We’re seeing more and more women not eating traditional meals,” she said excitedly. “It’s a great thing for snacking.”

New York Times News Service