A robot is what a smart home needs

Tech giants to start-ups are trying to visualise how to put it all together

Colin Angle may run a robotics company but even he struggles to corral the automatons in his home. As the chief executive of iRobot, he has no complaints about his company’s Roomba self-piloting vacuum cleaners, of course.

But the co-founder of one of the world’s largest makers of domestic robots is frustrated with the expensive home automation system he installed at his home in Massachusetts a few years ago.

The heating cannot keep up with his oft-changing schedule and the biggest advance to his lighting is being able to turn on several bulbs with one switch rather than three. Maintenance visits are required all too frequently.

“Here I am, with 25 years as CEO of a robot company, using almost none of the power of a smart home system,” says Angle. “I was as excited as anyone when I put it in about snapping my fingers and having soufflés made. But it wasn’t the reality.”

Robots are starting to change the way we live, but not in the way that scientists predicted 50, or even 10, years ago. At a time when some technologists are fretting about the threat of killer robots being used on the battlefield, the coming wave of domestic robots are much more tame, or even mundane.

Rather than androids marching into our kitchens and living rooms, automation is creeping into our home appliances, security systems and even garages.

Yet while the addition of wireless connectivity has brought a semblance of intelligence to our thermostats and light bulbs, by turning our smartphones into remote controls for the “internet of things”, installing, using and managing all these new devices remains a labour of geeky love.

“There is a whole lot of experimentation around the space of connecting things but I would say it is not all successful — in fact, I would say it is almost all unsuccessful,” says Angle. “There is not enough benefit in the eyes of the consumer.”

A robot revolution has been predicted for centuries. Leonardo da Vinci is said to have created a mechanical knight in 1495 that could stand, sit, and move its arms. Yet we are still a long way from the “robot housemaid” that sci-fi author Isaac Asimov predicted in a 1964 New York Times essay would be available by now.

However, aside from some examples such as vacuum cleaners, Asimov, the author of ‘I, Robot’, was right about one thing 50 years ago: “Robots will neither be common nor very good in 2014, but they will be in existence.”

More recently, Bill Gates in 2006 promised a future in which “robotic devices will become a nearly ubiquitous part of our day-to-day lives”, thanks to advances in sensors, motors and processing power.

“We may be on the verge of a new era,” Microsoft’s co-founder wrote in ‘Scientific American’ magazine, “when the PC will get up off the desktop and allow us to see, hear, touch and manipulate objects in places where we are not physically present”.

Nine years later, Jeremy Conrad, an investor in early-stage hardware start-ups at San Francisco incubator Lemnos Labs, says that automation and robotisation are “major trends we are seeing” — but not necessarily for the reasons that Gates predicted.

“The reality is that the change is not in the core technology,” says Conrad. Because sensors and other components are being widely used in smartphones and other mass-market devices, the costs are falling for other applications too.

“That means a “smart” device, connected to an existing home Wi-Fi network, is much more accessible (and cheaper) than a professional home-automation system.

“There are a lot more good start-ups out there because they don’t need millions of dollars to get off the ground. Investors can now see a path to a product that people can afford,” says Conrad.

Defining what exactly a robot is, however, remains a controversial topic even among those who build and invest in them. “There are lots of things in our homes or our cars that exhibit robotic behaviour — we just don’t think of them as such because we have this vision of a humanoid robot,” says Jen McCabe, a director at electronics manufacturer Flex’s innovation unit.

“The robotic movement of Nest is behind the thermostat but [just because it isn’t visible] doesn’t make it any less robotic.”

The Nest thermostat, which was bought by Google for $3 billion last year, learns the comings and goings of family members to predict when to heat and cool a house, helping to save energy and ensure a comfortable home. Nest’s thermostat also communicates with its home security camera to know when to switch itself on and off, or with certain makes of cars, which tell the heating system when the driver is on their way home so it can warm up the house.

Other big tech companies are chasing similar goals. Amazon’s Echo, for instance, is an internet-connected speaker and music player that responds to its owner’s voice. This way, the Echo can be used to turn on and off Wi-Fi-enabled Philips Hue light bulbs and Belkin WeMo electrical switches, not with a Wallace and Gromit-style mechanical arm but by putting itself at the centre of a wireless network of connected devices.

Apple has its own plans for a “smart home” platform too, called HomeKit, that will make the iPhone and its Siri assistant the remote control for lights, garage doors and even front door locks.

For some in the robotics industry, though, these sorts of applications are not ambitious or useful enough — even if they serve as inspiration for what comes next.

Cynthia Breazeal, director of the Personal Robots Group at MIT’s Media Lab, describes her start-up Jibo as the “iPhone of robotics”. When it is released next year, Breazeal promises that a Jibo placed on a desk or kitchen counter will not only be able to see, hear and speak but learn a family’s habits, relay messages between family members, make helpful suggestions and reminders — and even provide companionship.

“Because of the mobile computing revolution driving large sales of cameras and microprocessors, it’s possible to build a compelling experience at a mass consumer price point that wasn’t even possible two years ago,” says Breazeal.

The device looks like a cross between a Dyson fan, a curvy desk lamp and Eve, the robot in Pixar’s Wall-E. It has already raised $3.7 million from pre-orders through crowdfunding site Indiegogo.

Breazeal is pitching Jibo, which will sell for about $750, as a “social robot” with its own personality and character that, she claims, will get to know its owners. “A significant part of the Jibo experience is when it’s just hanging out — the ambient persona, when it’s there but you’re not tasking it to do something,” she says.

Such traits are how Jibo will differentiate itself from smartphones’ virtual assistants such as Apple’s Siri, Microsoft’s Cortana or Google Now.

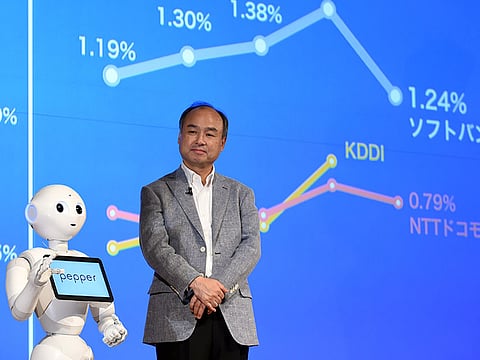

A more ambitious robotics venture is in Japan, where SoftBank has started selling Pepper, a 1.2 metre-tall humanoid robot that costs Y198,000 ($1,600). With two arms, big round eyes and a screen on its chest, the sleek white robot purports to be able to understand and respond to human emotions.

Bruno Maisonnier, co-founder of Aldebaran, the French company behind Pepper, which SoftBank acquired in 2012, told the FT that robots must ultimately look more like people if they are to “fight loneliness” — especially among older people — and aid communication.

“The majority of the message you send to someone isn’t through the words we are using, it is body language and expression,” says Maisonnier, a special adviser to SoftBank. “I need my robot to be able to read your body language and you to be able to read with your gut the messages the robot sends to you.”

There is a fine line between cute and creepy.

But Flex’s McCabe predicts that “therapy robots” will follow pets into our homes. “We want something we feel understands us. Just being heard sometimes is such a valuable thing.”

Yet she also warns of the challenges in selling general-purpose devices such as Pepper or Jibo to consumers, after working at now-defunct start-up Romotive, which made a small roving robot that used an iPhone as its brain and screen.

“The next-generation robots that are going to be really successful are going to be more specialised,” says Conrad. “They work every time and they are very reliable.”

“The giant enabler for connected intelligent home products is having enough context, in the cloud most likely, about the place that you live, in order for the machines that live there with you to understand what you are trying to do and how to help,” Angle says. “Your cleaning robot is, on a daily basis, exploring your home — so what better thing to make maps with?”

Understanding not only the layout but the purpose of each room, and the presence of people in it, will bring true automation to our homes, he predicts.

“It’s a very interesting time but ultimately connecting devices is giving hands to the body without the brain,” he says. “We need to build the brain for the hands to be useful.”

— Financial Times