Malfeasant Central Bankers, again

The drive to recapitalise banks will lead to a contraction of money supply

We are witnessing two inchoate, high-energy movements in the United States. The first — the so-called Tea Party movement — appeared in 2009. It is a quintessentially American revolt against the political establishment. The second — Occupy Wall Street — appeared little more than a month ago. It is also opposed to the same establishment.

But, unlike the Tea Party movement, Occupy Wall Street has international resonance. Perhaps the reason for that rests with the fact that many of the Tea Party movement's remedies hark back to a reliance on individual bourgeois virtues and a rejection of the welfare state.

In contrast, the remedy for the multiple grievances of the Occupy Wall Street movement all boil down to one big thing: a radical, state-mandated redistribution of income.

Indeed, Occupy Wall Street's mantra — tax the rich — is simply the second point in the ten-point action plan laid out in The Communist Manifesto: "A heavy progressive or graduated income tax."

In spite of their shared antipathy towards the establishment, it's as if the descendants of America's Founding Fathers were duelling it out with the offspring of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Never mind.

Let us step back from the street protests and identify the primary culprit of the huge economic dislocations that began in the fourth quarter of 2007. The application of Austrian Business Cycle Theory allowed practitioners to anticipate the crash. As for the culprit, all indicators pointed to the Federal Reserve (Fed). The Austrians weren't alone in anticipating the crash and fingering the Fed, however.

Amazing prediction

The followers of Professor Hyman Minsky foresaw a Minsky Moment well in advance of the Panic of 2008-09. Dr Bob Barbera's book The Cost of Capitalism: Understanding Market Mayhem and Stabilising our Economic Future contains a clear Minsky-like diagnosis. But perhaps the most amazing prediction was made by Professor Fred Foldvary, a student of the 19th century American political economist and advocate of the "single tax" on land Henry George.

In a 1997 article The Business Cycle: A Georgist-Austrian Synthesis, Professor Foldvary wrote: "The next major [real estate] bust, 18 years after the 1990 downturn, will be around 2008, if there is no major interruption such as a global war."

Professor Foldvary's analysis also anticipated the perpetrator of the downtown — the Fed.

That said, the Austrian Business Cycle Theory is the most relevant because it hits the nail on the head when it comes to a critique of the specific thing that was (and is) driving the Fed's monetary policy: inflation targeting.

For the Fed, and for most other central banks, monetary policy boils down to hitting an inflation target, such as a 2 per cent annual growth rate in the consumer price index.

It's as if nothing else matters. But, one of the main lessons delivered by the late Friedrich Hayek, one of the early pioneers in Austrian business cycle research, is that a reliance on one magic index, such as the consumer price index, to guide monetary policy is a recipe for disaster. Indeed, Nobelist Hayek stressed that changes in general price indexes don't contain much useful information. He demonstrated that it is the divergent movements of different market prices during the business cycle that count.

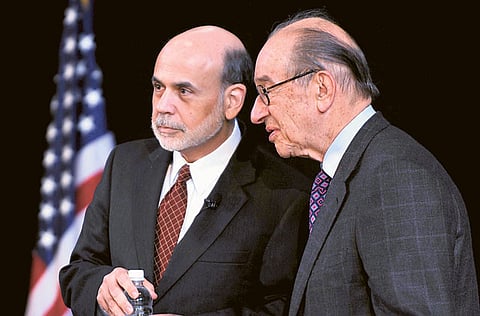

The accompanying chart of relative prices illustrates this perspective. Former Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan and his successor Professor Ben S. Bernanke — inflation targeters through and through — thought the economy was sailing smoothly on calm waters during the 2003-07 period.

After all, the consumer price index (less food and energy) was growing at a very regular "targeted" pace of 2.1 per cent per annum during that period. By contrast, the Austrians saw the huge relative price distortions in major commodity and asset groups. For example, share prices were accelerating at an 11 per cent annual rate during the 2003-07 period; housing prices measured by the Case-Shiller index were rising at an annual rate of 13 per cent during the 2003-2006 (first quarter) period; and commodity prices measured by the CRB index rose at a 13 per cent annual rate during the 2003-2008 (second quarter) period. For the Austrians, these surging prices and relative price distortions resulted from the Fed's ultra-lax monetary policy. They correctly anticipated that trouble was just around the corner.

Even after the Panic of 2008-09, the Fed (and other central banks) remains in denial, refusing to admit that monetary policy had anything to do with creating the bubbles that popped and the ensuing economic difficulties. The Deputy Governor of Sweden's Riksbank and a well-known pioneer of inflation targeting, Professor Lars Svensson, made clear what all the inflation-targeting central bankers have in mind.

"My view is that the crisis was largely caused by factors that had very little to do with monetary policy. And my main conclusion for money policy is that flexible inflation targeting — applied in the right way and in particular using all the information about financial conditions that is relevant for the forecast of inflation and resource utilisation at any horizon - remains the best-practice monetary policy before, during, and after the financial crisis," he said.

For central bankers, the "name of the game" is to blame someone else for the world's economic and financial troubles. How can this be, particularly when money is at the centre?

Biased reporting

To understand why the Fed's fantastic claims and denials are rarely subjected to the indignity of empirical verification, we have to look no further than the late Nobelist Milton Friedman.

In a 1975 book of essays in honour of Professor Friedman, Capitalism and Freedom: Problems and Prospects, Professor Gordon Tullock wrote: "…it should be pointed out that a very large part of the information available on most government issues originates within the government. On several occasions in my hearing [I don't know whether it is in his writing or not but I have heard him say this a number of times] Milton Friedman has pointed out that one of the basic reasons for the good press the Federal Reserve Board has had for many years has been that the Federal Reserve Board is the source of 98 per cent of all writing on the Federal Reserve Board. Most government agencies have this characteristic…"

Professor Friedman's assertion has subsequently been supported by Professor Larry White's research. In 2002, 74 per cent of the articles on monetary policy published by US economists in US-edited journals appeared in Fed-sponsored publications, or were authored (or co-authored) by Fed staff economists.

Now, under increased criticism and pressure, the Fed proposes to ramp up its capacity for snooping, harassment and mischief to new Orwellian levels. In September 2011, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York (FRBNY) solicited proposals from vendors who would "gather data from various social media outlets and news sources and provide applicable reporting to FRBNY.

This Request for Proposals (‘RFP') was created in an effort to support FRBNY's Social Media Listening Platforms Initiative."

If this isn't an invitation for trouble, I don't know what is. It might just ensure passage of the bills to audit the Fed, which are pending in the US House of Representatives (HR 459) and the US Senate (S 202).

Undercapitalisation claims

As part of the money and banking establishment's blame game, the accusatory finger has been pointed at commercial bankers.

The establishment asserts that banks are too risky and dangerous because they are "undercapitalised."

It is, therefore, not surprising that the Bank for International Settlements located in Basel, Switzerland has issued new Basel III capital rules. These will bump banks' capital requirements up from 4 per cent to 7 per cent of their risk-weighted assets. And if that is not enough, the Basel Committee agreed in late June to add a 2.5 per cent surcharge on top of the 7 per cent requirement for banks that are deemed too-big-to-fail.

The oracles of money and banking have demanded higher capital-asset ratios for banks. And that is exactly what they have received. Just look at what has happened in the United States. Since the onset of the Panic of 2008-09, US banks have, under political pressure and in anticipation of Basel III, increased their capital-asset ratios (see the accompanying chart).

The establishment has erupted in cheers at the sight of increased capital-asset ratios. They assert that more capital has made the banks stronger and safer. While at first glance that might strike one as a reasonable conclusion, it is not. For a bank, its assets (cash, loans and securities) must equal its liabilities (capital, bonds and liabilities which the bank owes to its shareholders and customers). In most countries, the bulk of a bank's liabilities (roughly 90 per cent) are deposits. Since deposits can be used to make payments, they are "money." Accordingly, most bank liabilities are money.

To increase their capital-asset ratios, banks can either boost capital or shrink "risk" assets.

If banks shrink their "risk" assets, their deposit liabilities will decline. In consequence, money balances will be destroyed. The other way to increase a bank's capital-asset ratio is by raising new capital. This, too, destroys money. When an investor purchases newly-issued bank equity, the investor exchanges funds from a bank deposit for new shares. This reduces deposit liabilities in the banking system and wipes out money.

So, paradoxically, the drive to deleverage banks and to shrink their balance sheets, in the name of making banks safer, destroys money balances. This, in turn, dents company liquidity and asset prices. It also reduces spending relative to where it would have been without higher capital-asset ratios. By pushing banks to increase their capital-asset ratios to allegedly make banks stronger, the establishment has made their economies (and perhaps their banks) weaker. This is certainly the wrong medicine to prescribe when the economy is weak. Professor Bill Barnett's new broad money measure — Divisia M4 — shines a bright light on the state of the US money supply (see the accompanying chart).

This market-based (in contrast to accounting-based) broad money measure gives us the most accurate dashboard metric available. A study of the Divisia M4 money-supply chart shows that the establishment has done it again. The push to recapitalise banks has thrown a monkey wrench into the money supply dynamics.

Steve H. Hanke is a Professor of Applied Economics at The Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore and a Senior Fellow at the Cato Institute in Washington, DC.