Changing times

A single calendar for the entire planet would simplify global business

For more than 500 years, the most popular and influential book, after the Bible, was The Golden Legend by Jacques de Voragine.* At the end of the 13th century Voragine grappled with the sacralization of time and its usage. Following the Council of Trent in the 16th century, the rules of time that, for the most part, have ruled Western civilisation, were established.

Recently, an interesting change occurred. On March 28, 2010, Russian President Dmitry Medvedev eliminated two of Russia's 11 time zones. Russia circles almost half the globe. Using our present 19th century method of marking the time, the clocks in Kaliningrad, far west of Moscow, read 10 hours differently (nine hours differently, after Medvedev's change) than clocks across the Bering Sea from Alaska. But, time, as measured by atomic clocks, is exactly the same in those two Russian locations. The time is the same everywhere, but the sun can be at very different locations in the sky — something that mattered in the 19th century far more than it does today.

Why did Medvedev make these changes? Imagine Washington D.C. on the US west coast and the US stretched over 11 time zones. If that were the case, when President Obama began work at 6am, it would already be 4pm on the (hypothetically stretched) East Coast, and all government workers would be going home in 30 minutes. Hard to keep in touch. That gives us a feeling for what Russia has to cope with. But Medvedev's solution, while mitigative, clearly does not totally solve the problem.

Yet, the problem is solvable for Russians, as well as for the rest of us, who are trapped both in temporal and calendrical messes. Our calendar is largely the product of disputes among churches — disputes important to those churches, but which should not be allowed to impact commerce and efficient business organisation today. The dates of Easter and of Christmas in Russia will always, of course, be set by the Russian Orthodox Church, but the Russian business calendar should be specified by Moscow, not by the Church.

There have been previous attempts to modernise and fix the calendar: George Eastman, founder of the Eastman Kodak Company in 1892 and a consummate man of business, was a strong advocate of calendar reform in the interest of business and commerce. Eastman favoured 13 identical months of 28 days. Writing in The Nation's Business (May 1926), Eastman complained that, with reference to the present Gregorian calendar, "there can be a difference of three days in the two half-years, and of two days in two quarters of the same year".

"Holidays occur on various days of the week, changing each year; shutdowns for holidays occurring in the middle of the week is expensive in certain plants. Complications arise in setting regular dates for meetings, in providing for holidays that fall on Sundays and in reckoning the passage of time, as for instance, in interest calculations," he wrote.

But Eastman's calendar drifted relative to the seasons, which is unacceptable. He suggested fixing that problem by adding occasional extra days that would not bear weekday names.

No exception

Eastman's effort at calendar reform failed because his proposed calendar did not respect the Sabbath. We propose a new calendar that preserves the Sabbath, with no exceptions. That calendar is simple, religiously unobjectionable, business-friendly and identical year-to-year. There are, just as in Eastman's calendar, 364 days in each year. But, every five or six years (specifically, in the years 2015, 2020, 2026, 2032, 2037, 2043, 2048, 2054, 2060, 2065, 2071, 2076, 2082, 2088, 2093, 2099, 2105, …, which have been chosen mathematically to minimise the new calendar's drift with respect to the seasons), one extra full week (seven days, so that the Sabbath is unaffected) is inserted, at the end of the year.

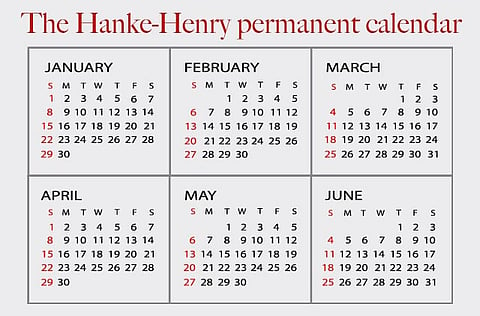

These extra seven days bring the calendar back into full synchronicity with the seasons. In place of Eastman's 13 months of 28 days, we prefer four identical quarters, each having two months of 30 days and a third month of 31 days (see the accompanying permanent calendar**).

That modern calendar would simplify financial calculations and eliminate the "rip-off factor". To determine how much interest accrues for a wide variety of instruments — bonds, mortgages, swaps, forward rate agreements, etc. — day counts are required. The current calendar contains complexities and anomalies that create day count problems. In consequence, a wide range of conventions has evolved in an attempt to simplify interest calculations.

Bond impact

For US government bonds, the interest earned between two dates is based on the ratio of the actual number of days elapsed to the actual number of days between the interest payments (actual/actual). For convenience, US corporate, municipal and many agency bonds employ the 30/360 day count convention. These different conventions create their own complications, inefficiencies and arbitrage opportunities.

Specifically, discrepancies between the actual/actual and 30/360 day count conventions occur with all months that do not have exactly 30 days. The best example comes from calculating accrued interest between February 28 and March 1 in a non-leap year. A corporate bond accrues three days of interest, while a government bond accrues interest for only one day. The proposed permanent calendar — with a predictable 91-day quarterly pattern of two months of 30 days and a third month of 31 days — eliminates the need for artificial day count conventions.

What will it take to produce regular dates and times throughout Russia and the rest of the world? Nothing but the will to do so. With regard to the regularisation of times and dates, Russia has the most to gain, particularly when it comes to time.

Moving on from the calendar to time, we recommend the abolition of all time zones, as well as of daylight savings time, and the adoption of atomic time — in particular, Greenwich Mean Time, or Universal Time, as it is called today. Like the adoption of a modern calendar, the embrace of Universal Time would be beneficial.

For example, the adoption of Universal Time would give new flexibility to economic management in the vast East-West expanse of Russia: everyone would know exactly what time it is everywhere, at every moment. Opening and closing times of businesses could be specified for every class of business and activity. If thought desirable, banks and financial institutions throughout the country could be required to open and to close each day at the same hour by the world time. This would mean that bank employees in the far East of Russia would start work with the sun well up in the sky, while bank employees in the far west of Russia would be at their desks before the sun has risen. But, across the country, they could conduct business with one another, all the working day. This would have a second benefit: at least in the far east and far west, the banks would be open either early or late, convenient for those who are working "sunlight hours," such as farmers. With Universal Time, agricultural workers, critically dependent on the position of the sun, could rise with the sun, without producing any impact on other aspects of cultural and economic life. The readings on the clocks, and the date on the calendar, would be the same for all. But times of work would be attuned with precision to Russia's local and national needs. China already has adopted a single time zone for the same purposes. And all aircraft pilots, worldwide, use Universal Time exclusively, for exactly the same reason that we are advocating its broad adoption — plus avoiding collisions.

Identical everywhere

Moscow could introduce both a simplified calendar, identical each year (harmonised with the seasons by rare full-week adjustments at year's end), and Universal Time, which would abolish the International Date Line, making the date and the time identical everywhere, including Alaska and the farthest eastern regions of Russia. There, and also in the centre of the Pacific Ocean, the date would change at 00:00:00, just as the sun passed overhead.

The natural date for the introduction of these changes is January 1, 2012, because it is a Sunday in both the current Gregorian calendar and the simple, new calendar. That does not give us time to change over computer programs to the new, simpler system, of course. But that does not matter — the change worldwide will take some time, politically, with a natural completion date of January 1, 2017, when Sunday will, once again, fall on January 1 for both the old and the new calendars. This gives a more than ample five-year transition for adjustments to computers. There is nothing magic about these dates; anyone can transition today if they wish. But absent national and international agreements, that could be confusing.

We should not worry about confusion, however. Again, look to Russia: in addition to abolishing time zones, daylight savings time was abolished in 2011. There was some disorder, as with iPhones ringing at "wrong" hours, but this passed!

Our proposed temporal and calendrical changes would eliminate the sources of an untold number of errors and generate immense benefits. Conference calls would be unambiguously scheduled. At present, a conference call is, say, scheduled for 3pm Central Daylight Time, and conferees across the US have to figure out when to pick up the phone. All that would be history — no more time zones, no more daylight savings time. One time throughout the world, one date throughout the world. Refill dates for prescription drugs would be the same day of the month, every month, every year. Business meetings, sports schedules and school calendars would be identical every year.

Today's cacophony of time zones, daylight savings times, and calendar fluctuations, year-after-year would be over. The economy — that's all of us — would receive a permanent "harmonisation dividend".

- *Note: For those who want to delve into the intricacies of The Golden Legend, see: Jacques Le Goff. A la recherche du temps sacré: Jacques de Voragine et la Legende dorée. Paris: Perrin, 2011.

- **The Hanke-Henry Permanent Calendar can be found here

Steve H. Hanke is a Professor of Applied Economics at the Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore and co-director of the Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health and the Study of Business Enterprise. Richard Conn Henry is a Professor in the Henry A. Rowland Department of Physics and Astronomy at the Johns Hopkins University and the director of Maryland Space Grant Consortium.