Iran's currency, the rial, has plummeted to its lowest value against the dollar in more than two decades after President Obama signed legislation last Saturday targeting Iran's Central Bank.

The rial dropped almost 30 per cent in two days, hitting exchange rates as low as 17,800 rials per dollar on Monday as Iranians rushed to sell their local currency holdings in favour of havens such as the euro, the UAE dirham, the US dollar, and gold.

Washington's new financial legislation against Teh-ran will sanction foreign firms that purchase Iranian oil — by far the chief source of Iranian government revenue — and penalise banks engaging in financial transactions with Iran.

The legislation won't be enacted for another six months, in order for the White House to prepare for any potential fallout on global oil prices, and the rial strengthened on Wednesday somewhat to 16,200 rials to the dollar.

But the psychological impact on ordinary Iranians, who see a strong rial as a sign of national strength amid the Islamic Republic's growing international isolation, has been huge.

"Obama's decision was a spark. There is an air of panic and people are worried," says George Washington University economist Hussain Askari, an expert on Iran's macro-economic policies.

"If Iran's Central Bank or entities that deal with the Central Bank are going to be sanctioned, it means Iran's ability to import goods and finance imports will be more costly and pressure its foreign exchange reserves."

Iran's Central Bank, which serves as a clearinghouse for nearly all oil and gas payments in Iran, has faced increasing difficulty over the past year in facilitating foreign currency transactions abroad.

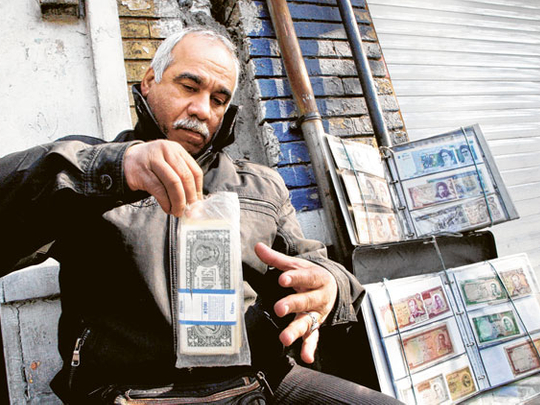

Monetary policy inside the Islamic Republic is facilitated by buying and selling currencies through a network of money-exchange dealers throughout Iran, Europe and the Middle East, allowing Tehran to maintain the rial within a range determined by the Central Bank.

By hindering the National Iranian Oil Company's ability to transfer oil revenues back to Tehran and by reducing the Central Bank's access to foreign exchange reserves held overseas, US Treasury sanctions have therefore limited the Central Bank's ability to control the depreciation of Iran's currency.

Last year, the Central Bank put a cap of $2,000 on the amount of currency private Iranian citizens looking to travel abroad could take out of government banks at the official rate of 11,180. Any foreign currency purchases beyond the Central Bank's $2,000 limit for private citizens must be made at the higher market rate for Iran's currency.

When the latest sanctions signed into law by President Obama are implemented, they could theoretically target the smaller, local banks in US-allied countries such as the UAE, Malaysia, or Turkey that Iran has had to use to transfer cash back to Tehran.

Second major shock

Monday's drop in Iran's currency value was the second major shock to Iranian markets in the past few weeks.

In late December, the rial dropped 10 per cent in less than a day after Iran's semi-official Mehr News Agency reported that Iran's Central Bank had ordered local businesses to stop using the UAE dirham for financial transactions.

That report cited Iran's ambassador in Abu Dhabi as saying that Tehran's Trade Promotion Organisation would no longer allow registration for imports routed through the UAE.

Tehran's market exchange rate quickly stabilised to just above 13,800 rials to the dollar after Iran's Foreign Ministry formally denied any trade cuts with the UAE or halts in registration, and the reports were removed from Mehr's website.

Financial experts inside the Islamic Republic say the added political shock of the new US legislation means that although Iran's market rate for the rial will stabilise, likely in the next few days, it won't recover back to the 14,000 rials-to-the-dollar range it was at last week.

Defiant regime

The Iranian government has remained defiant in the wake of Washington's latest sanctions over Tehran's controversial nuclear energy programme. Tehran announced the production of Iran's first nuclear fuel rod, has threatened to choke off the vital Strait of Hormuz — through which nearly one-fifth of global oil shipments pass — in the case of embargoes against Iranian oil, and conducted naval war games, including the test-firing of new missiles.

Nevertheless, Tehran has simultaneously sought to temper its recent aggressive posturing, renewing calls on December 31 to restart negotiations over its nuclear programme with the so-called P5+1 powers.

That group includes the five permanent members of the UN Security Council — the US, Britain, France, China, and Russia — plus Germany.

Domestic analysts say that while President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad's government is eager for new nuclear talks, the regime as a whole isn't likely to tone down its demands to negotiate on an "equal footing" with the economically and politically stronger P5+1 powers, and will surely maintain the government's now-trademark defiant tone.

"On the streets of Tehran the money exchangers are also under pressure," says Professor Askari of George Washington University. "If another spark occurs, there is really no limit on where the rial could go."

— The ChristianScience Monitor