New York: Moments after their hopes of undoing Obamacare unravelled, President Donald Trump and top Republicans said in unison that they’re moving on to another ambitious goal — overhauling the US tax code.

“We will probably start going very, very strongly for the big tax cuts and tax reform,” Trump said to reporters Friday after the House bill was pulled from a scheduled floor vote. “That will be next.”

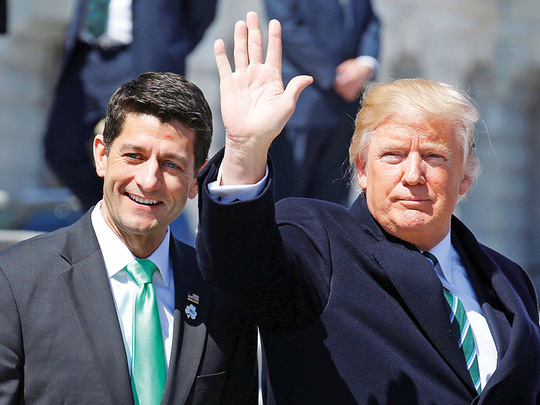

House Speaker Paul Ryan told reporters that Republicans will proceed with tax legislation — and said he met with Trump and Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin earlier on Friday to discuss taxes. Ryan sounded a note of caution: The health bill’s failure “does make tax reform more difficult,” he said, “but it doesn’t in any way make it impossible.”

Even before the health bill was withdrawn, two of the Trump administration’s top economic officials were shifting the conversation toward taxes. Mnuchin and White House Budget Director Mick Mulvaney both said Friday that the White House is at work on a plan for both individual and corporate tax changes that’s coming soon.

Still, Ryan’s frank assessment of his party’s missed opportunity on health care Friday afternoon might just as well apply to tax legislation. “Doing big things is hard,” the speaker told reporters.

Governing test

That sentiment reflected the mood of some anxious and frustrated Republicans, who were unable to muster enough votes in their first major test of governing in the Trump era. Several lawmakers said a complete overhaul of the tax code — which hasn’t been done in more than 30 years — would be tougher in the wake of the American Health Care Act’s defeat, as might the rest of their agenda.

“We have to learn that we’re not just the party of no,” said Representative Steve Womack of Arkansas, a member of the House GOP’s whip team. “We have to learn how to govern.”

This month, Trump, a billionaire businessman who touted his expertise on tax-avoidance strategies during his campaign, had at times seemed wistful about letting tax issues take a back seat to health policy. On Monday, during a campaign-style rally in Louisville, he told the crowd: “We want a very big tax cut, but cannot do that until we keep our promise to repeal and replace the disaster known as Obamacare.”

Now, he and fellow Republicans will face heightened political pressure to deliver on taxes, and the president’s tactics may have to evolve, lawmakers said.

Presidential lesson

“My guess is he has learnt through this process that politics is different from business,” said Representative Bill Huizenga, a Michigan Republican, on Friday afternoon. Lawmakers answer to their constituents, not the president, he said. “There’s no ability to sit at a table and say ‘You’re fired.’”

One difference that’s already apparent: Lawmakers and administration officials seem inclined to take more time on tax legislation. The health care bill was introduced, marked up, passed through committees and scheduled for a floor vote in just a few weeks. On taxes, House leaders have said they hope to pass a bill by August. Top Republican senators say it may take longer than that.

It’s unclear how Trump will propose to change tax laws. On Feb. 9, he promised a “phenomenal” tax plan in two or three weeks. That was six weeks ago.

His tax proposals changed over the course of his campaign — by Election Day, his plan had moved closer to the blueprint that Ryan and other House leaders prefer. Both plans would consolidate the number of individual income-tax rates to three from the existing seven; the top rate would drop to 33 per cent from 39.6 per cent currently.

‘Massive’ cut

Trump has said he wants a “massive” tax cut for the middle class, but independent analyses of the House tax blueprint have concluded that it would benefit high-earners far more.

On corporate taxes, Trump and Ryan have yet to forge an agreement — particularly over the controversial issue of “border adjustments.” Ryan favours replacing the existing 35 per cent corporate income tax with a 20 per cent tax rate on companies’ domestic sales and imports. Exports would be excluded.

That border-adjusted approach — which opponents say would increase consumer prices — has divided Trump’s White House advisers, and the president hasn’t yet announced a position on it. Leading Republican senators have also expressed reservations. Supporters say higher prices on imported goods would be offset over time by a strengthening dollar.

For all the controversy surrounding it, though, the border-adjustment concept would raise an estimated $1.1 trillion over 10 years, giving Republican tax-cutters breathing space for reducing the corporate rate. Losing that provision will make it more difficult to achieve revenue-neutral tax legislation, complicating its chances in the Senate.

Lower baseline

The failed health-care bill would have helped. It contained tax cuts of its own, about $999 billion worth over 10 years that would have been paid for by spending cuts — most of them in the federal Medicaid program that provides health care to the poor. Republicans said the resulting lower revenue baseline would have made a revenue-neutral tax overhaul that much easier.

Balancing revenue and cuts in the tax bill would allow it to bypass rules requiring 60 votes in the Senate, where Republicans hold only 52 seats. Democrats — none of whom supported the GOP health-care bill in the House — will be similarly wary on tax legislation, said Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer of New York. If the bill winds up benefiting the wealthy and not the middle-class, “it won’t fly either,” he said.

Democrats aren’t the only potential obstacles. As Ryan learnt in the health-care setback, the divide between moderate House Republicans and the conservative Freedom Caucus proved impossible to bridge. “The moderates in our conference and the Freedom Caucus are truly at opposite ends of the issues,” said Representative Chris Collins of New York, a Trump ally. “And so you get one, you lose one, you get one, you lose one.”

Mnuchin on Friday didn’t address such concerns, as he predicted a smoother glide path for tax legislation. “Health care and tax reform are two different issues,” he said during an event sponsored by the media company Axios. “Health care is complicated, tax reform is a lot simpler in some ways.”

‘Not discouraged’

Also upbeat was House Ways and Means Committee Chairman Kevin Brady, the House’s top tax writer, who said Republicans intend to go “full steam ahead” on a tax overhaul, “and we’re gonna work with the administration to get this done.”

“Look, we fought hard for Obamacare repeal, we did fall short,” he said. “I’m not discouraged.”

Still, much depends on Trump’s leadership; his advisers signalled on Friday that he’ll take an active role. “When you see tax reform the first time, it will be the president’s plan and we’ll drive the debate on that,” Mulvaney said during an interview on ABC’s “Good Morning America.”

To drive it effectively, Trump will have to change his ways, said Brian Walsh, a former Senate Republican leadership aide.

“He needs to engage early, often, and consistently, and take his message directly to the American people on the issues he cares about,” said Walsh, who argued that Trump was unnecessarily distracted on the health-care issue. “If the President heeds the lessons from this debate that could bode well for tax reform, but if he does not we could well see a replay of this mess in the months ahead.”

- Bloomberg