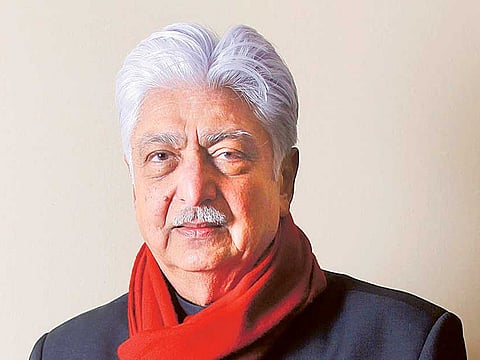

Azim Premji: making a positive difference

'India’s most generous man' has already donated more than $8 billion of his personal wealth to charity

Azim Premji is India’s most generous man, having donated more than $8 billion of his personal wealth to his eponymous foundation. In an exclusive interview, he describes his mission to transform public education, and help a new generation of Indian philanthropists to make a positive difference.

How did your philanthropic journey begin?

I became responsible for Wipro in the late 1960s, and for more than three decades I dedicated myself almost completely to building the business. During this time, I travelled extensively within India, and this gave me a first-hand view of the two extremes that had emerged in our country: rapid development and opportunities making people unimaginably prosperous, even as sections of society continued to be steeped in poverty and want.

I saw that many of those who remained in poverty lacked some of the basic amenities that any human being should have. It felt unfair and wrong: a society must take care of everyone, and those who are well off have a responsibility to do their bit to ensure that everyone’s basic human needs are met, and that opportunities are created for everyone to develop and grow.

So I had a very simple idea when I started: what could I do to contribute to a better India? To me, it meant that we must focus on the most disadvantaged and underprivileged.

Why did public education become your priority?

The only way that you can hope to make a difference is to focus on a specific social issue. For me, education stood out as the key process and building block of a good society. Its importance goes far beyond the economic opportunity it offers: it has a vital role in empowering individuals and societies alike — socially, economically and politically. If we really wanted to build a just, humane and equitable society — as envisaged in India’s constitution — then education would be the transformative force, and because children from the most disadvantaged families go to government-run schools, we knew that we had to work with the public system.

We don’t expect to achieve what we set out for in five or 10 years. We know it is going to take decades.

How has the foundation engaged with capacity building?

Today we work in eight states, which have about 350,000 schools, although of course we should remember that India has 1.5 million schools. Our foundation works very closely with all levels of the public education system — at the operational level in districts, blocks and clusters; at the level of institutions that support the operations; and at the policy level. We also work on all dimensions of the system, from capacity building among teachers and head teachers, to curriculum development, and assessment reform.

What do you hope will be the impact of your giving?

As well as visiting schools in the field, I also regularly interact with students at the Azim Premji University. These are remarkable people who could have had very lucrative careers [in the private sector] but have committed themselves to working in education, with all its complexities. There is meaning and purpose there, not financial reward or glamour, and I am very proud we have been instrumental in getting talented and committed people to work in the sector.

We hope one day to see an outstanding public education system in the country. When I say ‘we’, I don’t just mean our foundation, but all our partners and the government working together. We have to remember that social issues are complex and take a long time to change.

You have paid tribute to your mother as a significant influence on you. How did she inspire you?

My mother, Gulbanoo Premji, was one of the first qualified women doctors in the city of Bombay. In those days, men went to work and women usually stayed at home, and therefore, although she had a medical degree, she did not actually work as a doctor. However, she wanted to contribute to society, so she decided to help an organisation that worked with physically challenged children.

In the 1950s, the Children’s Orthopaedic Hospital opened at Haji Ali in south Bombay. She worked there tirelessly for almost 50 years. Every morning, vans went out to bring in children who needed treatment and care. Most of these children came from families in poverty, and they had to be fed as well.

My mother was unfazed by all of the challenges they faced, whether it was lack of funds or the management of staff. She was so busy, but she always found time for us. She was an inspirational figure, as was my father, and their selflessness and integrity shaped my thinking.

What do you tell your own children about philanthropy?

As a family, we spend a lot of time discussing what we are doing and attempting to do, but I don’t really ‘tell’ my sons about philanthropy. I don’t think that telling anyone, whether they are your own children or others, does much. People need to see, think and understand for themselves, as realisation is an intrinsic process, one that can be aided by open discussion, but cannot be forced. My sons are deeply engaged in different aspects of our philanthropic work, and they are making their own discoveries.

In February 2013 you signed the Giving Pledge. Why did you choose to make this commitment?

I have always considered myself a trustee of the wealth and was very clear that I would give a substantial part of my wealth away. Participating in the Giving Pledge was a kind of formalised communication, something that would help start a discourse on personal philanthropy and provide a fillip to philanthropy in India.

In my opinion, India’s business leaders have always been quite socially aware. If you study some of the old business families — such as the Tatas, Birlas, Bajajs, and Murugappas — you will find they have been active in philanthropy for many decades, and in some cases, for over a century.

Philanthropy can never substitute the government’s work, let us be clear on that. Ultimately, overall social development requires strong public services, which have to be provided by government. But philanthropy can play a crucial role in helping the public system, filling gaps it is not able to address and taking on high-risk projects that it cannot fund.

How important is it that there are philanthropic role models for the younger generation to emulate?

Traditionally, philanthropists in India have been very discreet about their giving. As a country, we have believed the idea of giving should be for others and society, not for self-promotion, and that makes perfect sense. In the last few decades, however, we have seen significant wealth creation in the country and many of the newly wealthy are very serious about understanding and addressing social issues. I feel it is important to have a discreet and thoughtful engagement with them, to start a discourse. This is what we are trying to do through the India Philanthropy Initiative, an informal effort I am driving with a few other like-minded individuals.

I refrain from passing on advice and generally ‘telling’ people what to do. However, I hope my reflections might help some who are contemplating engaging in serious philanthropy. Whenever people seek my advice, I always encourage them to start early: social change takes time, and the sooner you start the better chance you have to make a positive difference.

PROFILE

A passionate philanthropist

Azim Premji is the chairman of Wipro Ltd, the seventh largest IT company in the world and one of the largest publicly traded companies in India. He is also a passionate philanthropist who has spent decades working to alleviate poverty and inequality.

Since 2001, he has done this through the Azim Premji Foundation, which works at primary school level to test new approaches in education with the potential for systemic change, and the Azim Premji University, which offers programmes to develop education and development professionals, and also invest in educational research.