A living legacy

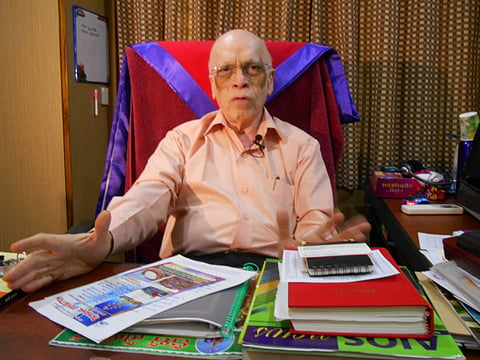

Dr Chandrasekhar Sankurathri keeps the memory of his wife, son and daughter alive through philanthropic work

Kakinada, INDIA

Some 65 kilometres from Rajahmundry airport in Andhra Pradesh, on the black-tarred state highway that snaked its way past lush green paddy fields and sporadic rural settlements, a giant signboard of Manjari Sankurathri Memorial Foundation hangs over red soil.

It was a stark reminder of what Dr Chandrasekhar Sankurathri, an Indian-origin former biologist with the Canadian government, had created in his native village near the port city of Kakinada in Andhra Pradesh to immortalise the fond memories of his wife Manjari, son Srikiran and daughter Sarada. It was Chandrasekhar’s way of “giving back to society for all that society has done for us and to help all those who are not so privileged”.

The bomb on Air India Flight AI 182 plucked Manjari, Srikiran (then six years old) and Sarada (three years old) out of the sky, like the 326 others on that ill-fated Boeing 747, and created a void in the life of Chandrasekhar — a void so huge that it forced Chandrasekhar to seek a new meaning and purpose in life through philanthropy.

The Manjari Sankurathri Memorial Foundation, Srikiran Institute of Ophthalmology and Sarada Vidyalayam were born out of one man’s dogged determination to salvage some meaning out of a world turned topsy-turvy by a sudden, cruel gust of fate.

“After that incident, there were many questions in my mind, but there were no answers. I was just wondering what to do with my life. After two-three years’ of deliberations, I finally told myself that maybe there is something meaningful that I should do with my life, instead of feeling sorry for myself and instead of just going to work and coming back home.

“I wanted to work with children. So I quit my job in Canada and came back to India. And today, I feel God has given me this opportunity to utilise my life in a much better way, where I can change several thousands of lives – both, in terms of education and eye-care. We also have another initiative called Spandana, which helps people at the time of natural disasters. But primarily what we are looking at is elimination of illiteracy and elimination of blindness among the rural poor.”

The sprawling campus that houses the foundation, the school and eye-care hospital has greenery all over. A manicured bed of flowers, carefully-pruned shrubs and a fountain lead one into the building that houses the eye-care unit. Right at the end of the long passageway is a glassed closet bearing an oil painting of a happy threesome: Manjari, with Srikiran and Sarada. An oil lamp keeps burning night and day and a tray of floral tribute at the foot of the closet completes the scene -- as time stands still.

Six-year-old Srikiran had told his father that he wanted to become a “children’s eye-doctor”. Today, the ophthalmology institute named after him conducts critical corrective surgeries on neo-natals almost regularly. The day Gulf News was present at the eye-care institute, a five-day-old baby underwent a critical, retinal surgery.

“This newborn, delivered premature, had ruptured blood vessels in his right eye owing to an over-supply of oxygen in the incubator. So our medical team brought him over from the hospital where he was born and conducted the surgery early this morning,” Chandrasekhar informed. A visibly satisfied mother of the child, Shruti M., later told Gulf News: “We were sure the kind of treatment we would get here would be difficult to match by any other hospital or clinic in the vicinity ... and for that price. We are so grateful to this place.”

While in Canada, Chandrasekhar had heard about a charitable organisation there that used to fund an orphanage in India. “During one of my holidays, when I came to India, I visited this orphanage because I wanted to do something for it in my own small way. But I didn’t quite like what I saw and the suggestions that I had were not taken too kindly. So I told myself that instead of joining an organisation formed by someone else, why not have a charitable body of my own? That was the turning point,” Chandrasekhar said.

While education offered at Sarada Vidyalayam is absolutely free, 90 per cent of the surgeries performed at the eye-care institute are also free of cost. The school, apart from providing free books and stationery to students, also offers free midday meals and transport.

The charity called Manjari Sankurathri Memorial Foundation was established in Canada and was registered as a national charity there in 1989. “But we were not sure whether a charitable trust established in Canada would be allowed to work in India. So to avoid any complication, we thought it best to start an Indian arm,” Chandrasekhar explained.

When Chandrasekhar heard that Kanishka had crashed into the Atlantic, he just couldn’t believe it.

“For many months after the crash, I kept on hoping that one day, my wife and children will come back. I had seen everything on TV and had even been to the crash site in Cork just after the incident. Yet, I kept on hoping that they were still alive and would come back,” Chandrasekhar said, weighing each word carefully, even as a pall of glom descended on his cabin.

“I still remember seeing off my wife, son and daughter at Montreal airport. They were so happy … that’s the image I still have of them. Lively, happy people … that is what I still remember.”

Even today, whenever a young man walks into his cabin with his CV, one of the first things that Chandrasekhar inquires about is the year of his birth. “And if someone says that he was born around 1978-79, I try to imagine what my son would be like … maybe somewhat like the guy standing before me …,” his voice trails off, the eyes bear a distant look.