The world in India's shopping bags

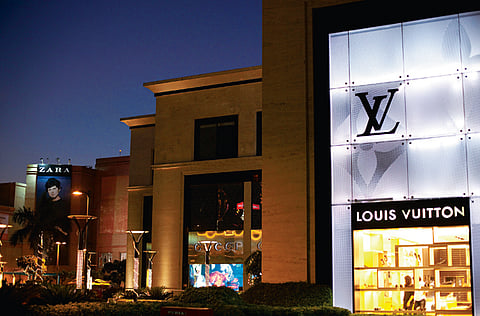

Everyone, from UAE brands to Paris Hilton, wants a slice of India's retail pie as foreign direct investment opens up. But buying into the world's largest democracy could give them serious indigestion

Experts call this the most exciting time for India's retail industry. The government has allowed 100 per cent foreign direct investment (FDI) in single-brand retail, paving the way for Ikea, Armani and Rolex to open fully owned stores in India, conditionally. The proposal to allow 51 per cent FDI in multi-brand retail remains suspended until the conclusion of assembly elections in seven states this quarter, even as Prime Minister Manmohan Singh's government works towards a consensus after the outcry following the initial November decision to reform the sector.

FDI is inevitable

Industry analysts have long maintained that FDI is inevitable. Political leaders, industrialists and industry bodies have been vocal in their support. Riding on the back of this optimism, international retailers have long been brushing up strategies to enter the market when it does eventually open up.

While research firm Business Monitor International says the Indian retail market is estimated to double to $785 billion (about Dh2.8 trillion) by 2015, from $396 billion last year, statistics put current operations of foreign retail chains at only 7 per cent of the total market.

Among these, retailers from the UAE have enjoyed several natural advantages in India. "Many Middle East retailers either have Indian ownership or Indian professionals at the top. They understand the market culturally. When they looked to expand out of the Middle East from 2006 onwards until 2008, they focused on Egypt, Turkey, Poland and Russia. It is a natural progression to India," says Shubhranshu Pani, Managing Director — Retail Services, Jones Lang LaSalle India, in an interview with GN Focus.

Many UAE companies, including Jashanmal, Damas, Jumbo and Joyalukkas have already ventured into the Indian market with varying degrees of success. Lulu is set to create one of India's biggest malls in Kochi, Kerala. Lifestyle International, a part of Dubai-based Landmark Group, has been in India for more than a decade, and is set to grow exponentially.

"Doing business in India is different," says Kabir Lumba, Managing Director, Lifestyle International. In its 11-year presence, Lumba says, the company has only focused on expansion in the last five years. But having cracked the code, it is now set for rapid growth. Ashwin Puri, CEO, Property Zone, which provides integrated infrastructure solutions for retail developmental needs, says the country offers great prospects: "For international brands, the Indian market poses a greater opportunity. Brands can roll out a few hundred stores in a short span, unlike in the UAE."

Economies of scale and a burgeoning middle class with disposable income are attractive to retailers. Even if regulations permit FDI in multi-brand retail only in cities with a population of one million or more as has been suggested, there are 53 of those.

Growth challenges

Attractive as it is, growth is not simple. "India takes two or three years to understand. We have seen it happen to every retailer, Indian or international. If he manages to succeed earlier, we call him lucky," says Pani. Lifestyle International already has 32 Lifestyle, about 60 Max and 12 Home Centre stores in India. Its three-to-five-year plans include opening 45 Lifestyle stores, about 100 Max stores and 18 to 19 Home Centre stores.

Drawing upon his experience, Lumba says that India is not the place for a "cut and paste" module. "First, there is a real estate challenge — costs are higher, malls are not well-designed — then, there is pressure on pricing, since the market is more price-sensitive."

Creative solutions are needed to cope with infrastructure issues in India. Due to land cost and availability issues, store sizes are smaller and occupancy costs higher. While anchor stores enjoy rate parity in rents with international markets, other stores may pay about double of what is probably the norm in the US. "The consumption in the US is more than India. An Indian store does one third of business compared to a US one," Pani says.

Also, many international retailers are not used to the Maximum Retail Price (MRP) policy, which requires that the price that a retailer can demand, including all taxes, be set in advance and displayed on packaging. "Most are used to free price regimes. In India, they cannot sell at more than the MRP. They can only give discounts or sell at less," Pani says.

Though enticed by the opportunity, companies are taking various routes to India, entering the more liberal wholesale trade, franchising and joint ventures. Dr Prodipta Sen, Executive Director, Alpha G:Corp, owners of AlphaOne shopping centre in Amritsar, Punjab, says Bharti-Walmart, which operates six wholesale stores in the country, has grown with a unique partnership. "The company approached the state government to maintain and modernise slaughter houses. The partnership helped it source hygienic meat for its Best Price Modern Wholesale shops that currently cater to about 1.85 lakh [185,000] registered consumers in the country, with four stores operating in Punjab alone." French retailer Carrefour, which runs a wholesale store in Delhi is also showcasing its commitment to the country, while it awaits final FDI clearance for multi-brand retail. >

It has adopted a municipal school near its wholesale store and has tied up with Delhi's Municipal Corporation .

Furniture retailer Ikea, which has stayed away saying that it will only set up on its own, has been sourcing products from India for a long time and funds initiatives in the carpet and cotton regions in the country.

These programmes allow companies a foot in the door, which has helped in creating a pro-FDI lobby.

India's organised retail is still nascent compared to the more mature markets that international retailers are used to. Learning lessons from the economic downturn, shopping centres in India have uniformly adopted international practices such as revenue-share systems, instead of lease-only models popular until a few years ago.

"High occupancy cost continues to be an issue. What retailers are doing, in a few cases, is to structure transactions in such a way that lease terms are favourable in the first six months of operation, allowing them breathing space," says Puri, whose company manages one of India's most successful malls, R-City in Mumbai's Ghatkopar suburb.

One of the key differences between the two countries, he says, is that in the UAE bold projects are executed even if the returns are lower as these projects help market the country. "The UAE has addressed the resource problem by not shying away from getting international experts. This ensures that the learning process is shortened and one can see world-class developments," Puri says.

Four become one

Retail consultants say that due to its size and a customer that defies homogenisation, successful retailers in India must have policies specially created for the country. After all, some Indian cities are bigger than some countries that international players deal with.

Indeed, all experts have anecdotes about big crashes in India — there is one about an international high-fashion brand that launched in India with an entire winter-wear collection. "It failed miserably — we have only a three-month winter," says Pani.

He cites his experience in soliciting retailers in South Africa to look at India about five to six years ago. "They told me," he says, "we have evaluated the country and what we see in India is actually four countries."

Lifestyle too has established a policy for India different from its other markets. "Five to six years ago, we started wholehearted localisation. In the Middle East, for instance, our central sourcing office buys for all the countries [where our stores are located]. In India, we buy need-specific local products, such as salwar kameezes," Lumba says.

It is a decision foreign brands would do well to emulate, considering that under the new notification, 100 per cent FDI in single-brand is conditional upon 30 per cent sourcing from small and medium-sized industries in India.

For those entering India, the astute evaluation is necessary. "In South, West and North, the physical proportions are different, so sizing is affected. The climate is vastly different, so you are catering to different clothing needs. Affinity to colour is different, so the colour forecasts are affected," Pani says.

Dr Sen, whose company owns a shopping centre in Ahmedabad in Gujarat, tells us that Kentucky Fried Chicken (KFC) had its waiters wear different-coloured uniforms while serving vegetarian and non-vegetarian meals in the state with a largely vegetarian population.

While analysts say the notification is likely to lead to a positive stance on FDI in multi-brand retail soon, partnerships are not likely to give way to ownership in a hurry. UK-based retail apparel chain Marks & Spencer has already declared its intention of continuing its partnership with Reliance to expand its India footprint. Benetton is likely to operate like a wholesaler and follow the franchise route in India.

In the atmosphere of general cheer, Pani cautions that each retailer has to relearn strategy, whether it be about what sells or it should be sold. Pani ends with a word of caution: "One has to look at what is available, rather than follow all international norms. There are cities where there are no large plots, so one has to go vertical, in others there may be land, but infrastructure may be an issue. It is imperative to be local. There is no single formula."

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox