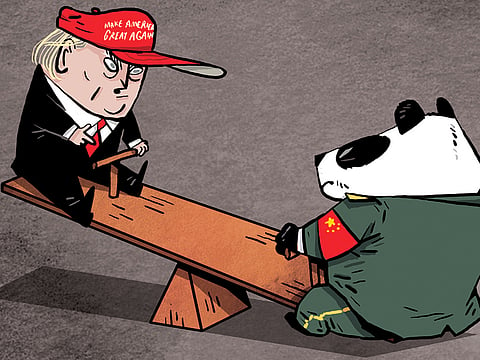

US-China relations at tipping point

Trump ideally favours a wider grand bargain with Beijing extending beyond the economics arena to other security issues too

Washington is poised this week to impose tariffs on some $34 billion (Dh125 billion) of Chinese goods in what could tip the two sides into a trade war. This latest bout of bilateral turmoil could severely disrupt what is probably the world’s most important economic and political bilateral relationship at what is already a time of wider global angst.

As the United States-China conflict over trade has intensified, Beijing has increasingly sought to align itself with Brussels, given that the European Union (EU) is also currently in dispute on this economic front with US President Donald Trump. Last week, in Beijing, Chinese Vice-Premier Liu He and European Commission Vice-President Jyrki Katainen vowed to oppose US trade protectionism asserting that unilateral actions risked pushing the global economy into recession.

Trump is again placing great emphasis on his personal skills of negotiation to resolve these issues. Last week, he asserted that “we have started the process and I think that will work out with China because we have a very good relationship with President Xi Jinping. He is incredible”. Yet, despite Trump’s optimism here, it is by no means certain that Beijing will play ball with Washington. And this despite the current upswing in ties between the two superpowers which has seen significant cooperation on North Korea, for instance, lead to the Singapore summit earlier this month between the US president and Kim Jong-un.

For underneath this apparent success of US and Chinese diplomacy and coercion in bringing Kim to the negotiating table, bilateral ties remain mixed and it is unclear how much personal chemistry Trump and Xi have in practice. This is relevant as, while economic and security fundamentals will largely determine the course of ties in coming years, personal warmth between the two leaders could also be key.

During the Obama presidency, the fact that bilateral relations remained generally cordial reflected, in significant part, the personal commitment of former US president Barack Obama and Xi to stability. Both recognised the super-priority of the relationship, and Washington pursued a strategy that promoted cooperation on softer issues like climate change, while seeking constructive engagement on vexed, harder issues such as South China Sea tensions.

Meanwhile, Xi outlined his desire to fundamentally redevelop a new type of great power relationship with the US to avoid the conflictual great-power patterns of the past. This is an audacious goal, which still lacks any obvious definition, and it is not certain how long the pledge will remain in place given the frequent bellicosity of Trump to China.

For while Trump is quite often warm in his rhetoric toward Xi, personally, it is clear that he genuinely believes China is a major threat to the United States. This is not only true on the economic front, but also the security domain too: Much of the US president’s anti-Beijing rhetoric appears to be based on a conviction that China represents the primary threat to US interests globally.

Outside of North Korea, a string of security issues still cloud the bilateral agenda, including the South China Sea, and US Defence Secretary James Mattis raised these issues in his first trip to China last week. This topic frequently brings frustrations for both sides and last year even the comparatively moderate-mannered former US secretary of state Rex Tillerson said Beijing should “not be allowed access” to its new, artificial islands there, a sensitive comment given China’s animus toward US sea and air manoeuvres near its borders.

Yet, it is economic disputes that are currently at the fore of the bilateral relationship. Whilst praising Xi last week, Trump asserted that “China ... has been very tough on our country ... We probably lost last year $500 billion in trade to China. Think of it: 500 billion”.

It is this narrative that Trump has repeated many times since the 2016 US election. As well as his concerns about US trade deficits and purported US job losses that come from this, he has repeatedly called Beijing “grand champions of currency manipulation”, asserting the country is keeping its exchange rate artificially low in order to secure export advantage.

On the face of it, therefore, rising tensions between Beijing and Washington appear very likely in coming weeks. Yet, such is the mercurial nature of Trump, it remains genuinely unclear how far he will now up the ante with Xi.

Ultimately, he needs to show his US political base some concessions from China on these issues to seek to fulfil his “America First” agenda. Here he has previously asserted that “everything is under negotiation”, and what he ideally favours — building on the recent diplomacy with Xi over North Korea — is a wider grand bargain with Beijing extending beyond the economics arena, where one of his key asks is to see the Chinese currency floated, to other security issues too.

If such a deal can be pulled off, it would potentially provide for greater overall stability in the world economy and limit damage to the currently creaking international trade system which risks being undermined further by a major US-China spat. An agreement of this kind could also have a broader positive effect on international relations, helping underpin a renewed basis for bilateral relations under the Trump presidency into the 2020s.

Andrew Hammond is an Associate at LSE IDEAS at the London School of Economics.