Rajoy is gone. Can Pedro Sanchez tackle the corruption plaguing Spain?

After years of conservative-led scandal and turmoil, the new prime minister must show social democracy still has teeth

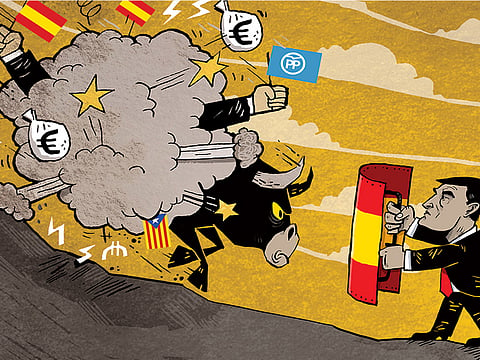

The surprise in Spain is not that the prime minister, Mariano Rajoy, has gone, but that he lasted so long. His conservative People’s party (PP) had been knee-deep in corruption scandals for years. So many of the party’s principal players were involved that it became impossible to blame a few rotten apples. The barrel itself stank of putrefaction.

Somehow, however, events conspired to keep Rajoy in power. It was only when his police began beating up citizens in the streets of Catalonia that the rest of the world woke up to what that might actually mean. The worst part of his legacy is a restriction of fundamental rights and his overempowerment of a police force that can now even fine people for taking photographs of suspected abuses.

Rajoy’s conversion of the constitutional court into not just an arbiter of right and wrong but an actor in the implementation of policy has produced a dangerous conflation of politics and justice that leaves the latter wide open to abuse. By weaponising the courts, he turned political problems — including those in Catalonia — into legal ones. It was a renunciation of responsibility and leadership.

Rajoy’s successes, however, point to why Spain’s new socialist prime minister, Pedro Sanchez, will now find it so hard to govern. His predecessor’s ability to hold on to power had as much to with disarray on the left as it did with his own considerable, if low-key, tenacity.

The dispute between social democracy and its leftwing contenders, represented by Podemos, has been as harsh as that between left and right. Can they now work together? All this is complicated further by the joyous abandon with which nationalists of all kinds have destroyed much of the common ground that unites the Spanish.

Sanchez is the overnight sensation of an otherwise moribund political beast — European social democracy. He may also be its last hope. He has the poster-boy appeal of a Justin Trudeau or an Emmanuel Macron, and the same tendency to occupy a broad stretch of centre ground.

Sanchez has a far steeper mountain to climb, however, than either of the other two heroes of what may eventually become a new centrist consensus. Many voters recall that it was Sanchez’s party, under the former prime minister Jose Luis Rodriguez Zapatero, that first sacrificed the welfare of ordinary Spaniards on the altar of Eurozone austerity. With Rajoy’s support, they changed the constitution, turning strict budget control into an absolute mandate and imposing a dramatic internal devaluation based on job and salary cuts. As a result, Spain is now the most unequal large country in Europe — above even the United Kingdom. The changes introduced to the constitution were proof that a document that Spanish politicians so often claim is untouchable can be altered in the blink of an eye — but only if Angela Merkel so desires.

There is, however, also hope in Spain. For the art of politics is still alive and thriving. While Italy churns and Britain rips itself apart over Brexit, even the supposedly radical left of Podemos is brimful of ideas and practical political solutions to everyday problems. It is also the country where, despite a huge influx of migrants at the beginning of the century, immigration is a non-issue. Were it not for the craziness in Catalonia, indeed, Spain could boast that this is the place where politicians have tried hardest to avoid the cynical drift towards demagoguery.

There has, however, always been a gaping hole in the proud story that Spaniards tell themselves about their post-dictatorship practice of democracy. That hole is called corruption. It ended the socialist hegemony of Felipe Gonzalez in the 1990s, has destroyed the rightwing era of Rajoy and has irretrievably damaged the reputation of his PP predecessor, Jose Maria Aznar.

Too often, politicians conflate public power with personal property. The court system is so sluggish that, when those who steal public funds are finally caught, it takes a decade or more to bring cases to trial. The final nail in Rajoy’s coffin, for example, was the preliminary sentence in a case that took nine years to prove that his party was systematically taking backhanders.

Even Spain’s version of the global financial crisis, where the economy is only now returning to the size of a decade ago, was aggravated by politically controlled savings banks that pumped extra air into an overinflated property bubble. Many of the politicians involved also lined their pockets along the way.

The fractious parliament that must now govern Spain should, in theory, be able to tackle systemic elements of corruption by insisting on greater transparency, speeding up the court system and increasing penalties.

Even if his government only lasts for a few months, that could be Sanchez’s single great legacy to his country. Social democracy has one foot in the grave. If he cannot deliver a solution to Spain’s political corruption, Sanchez risks burying it forever.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd

Giles Tremlett is the author of Ghosts of Spain and Catherine of Aragon